The

Bombing

of Quala 4131

Three strikes in an hour, and an Afghan family’s 15-year battle for justice

March 7, 2024

On June 17th 2007, Dutch-led NATO forces destroyed a residential complex in Chora, Afghanistan.

Between 3 and 4am, at least 11 civilians were killed in their quala - a walled, residential area where families often live together. It was one event in three days of violence known as the Battle of Chora, in which at least 60 civilians were killed.

A decade and a half later, a court case in the Netherlands found the Dutch military could not justify why the village was attacked. The Ministry of Defence said vital evidence must have been lost or destroyed, while the victims' lawyers argued it likely never existed.

In late 2022, the civil court ruled the Dutch military likely committed a breach of international humanitarian law (IHL), making the victims eligible for compensation. Advocates hailed the ruling as the first of its kind, setting a precedent that civilians caught in conflict should have a route to accountability.

“The ruling establishes a right to reparation in a civil court for individual victims from an IHL violation,” said Mark Lattimer, the head of the Ceasefire Centre for Civilian Rights. “That sounds like a very obvious thing, but in practice, outside human rights law, we haven’t seen many awards to civilian victims from IHL violations”.

Yet the 15-year process, and the complex legal wranglings, meant the landmark ruling received little traction outside military and expert circles.

Using hundreds of pages of internal documents, maps, logbooks and other filings from the court case, Airwars recreated the events to highlight the significance of the ruling for victims in conflict zones.

A video of one of the victims played during the court proceedings. In it, he asked: “Why did this happen? Why has so much damage been done to us? Why are we treated so cruelly?”

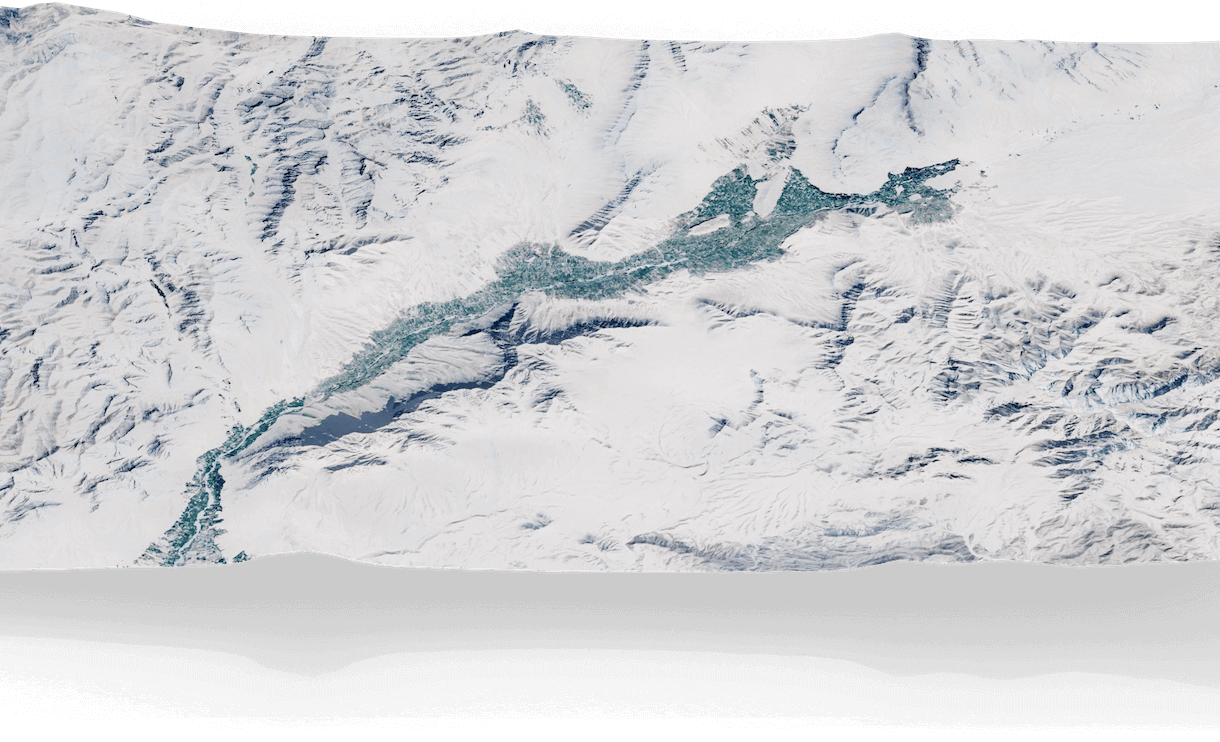

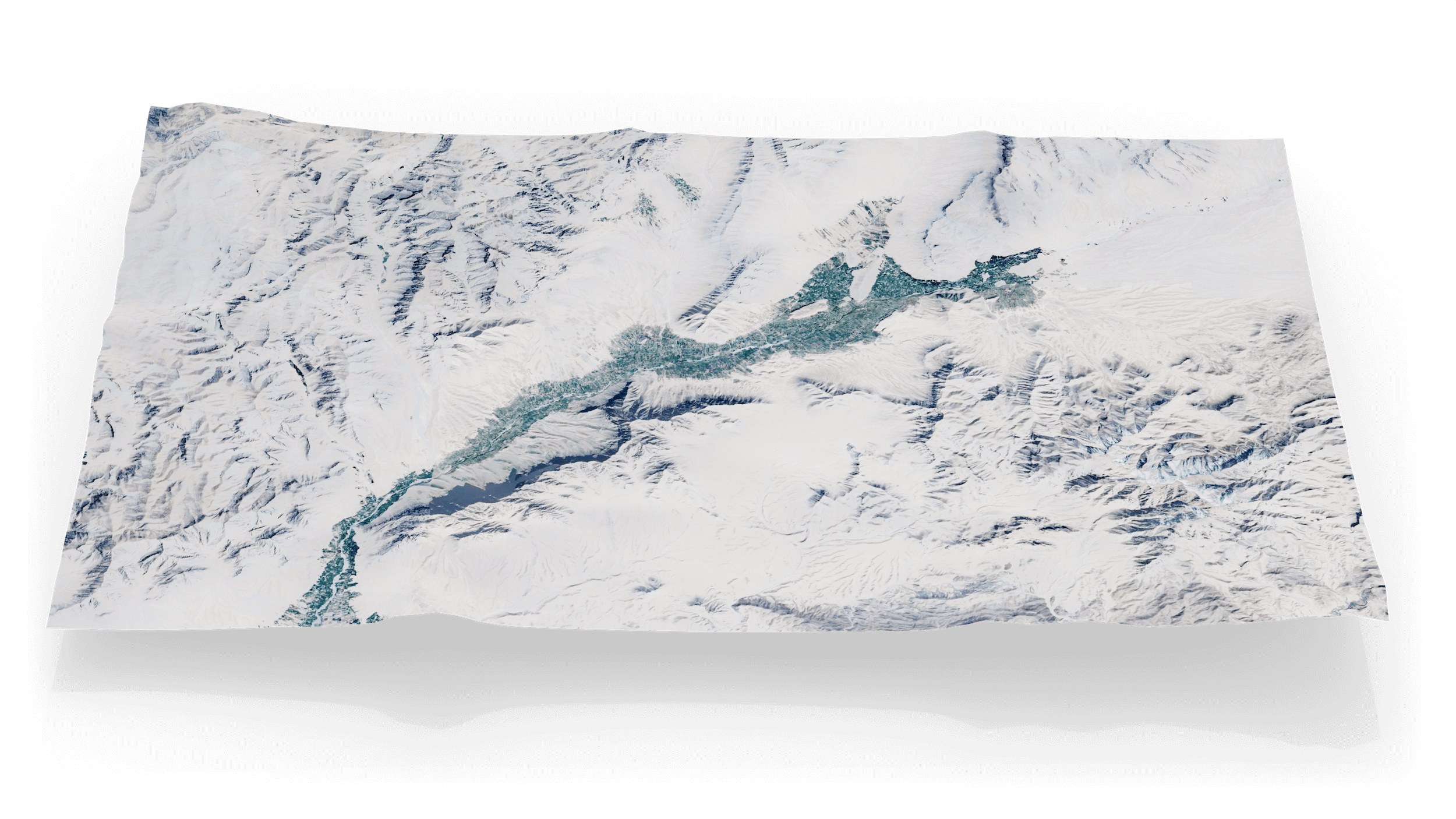

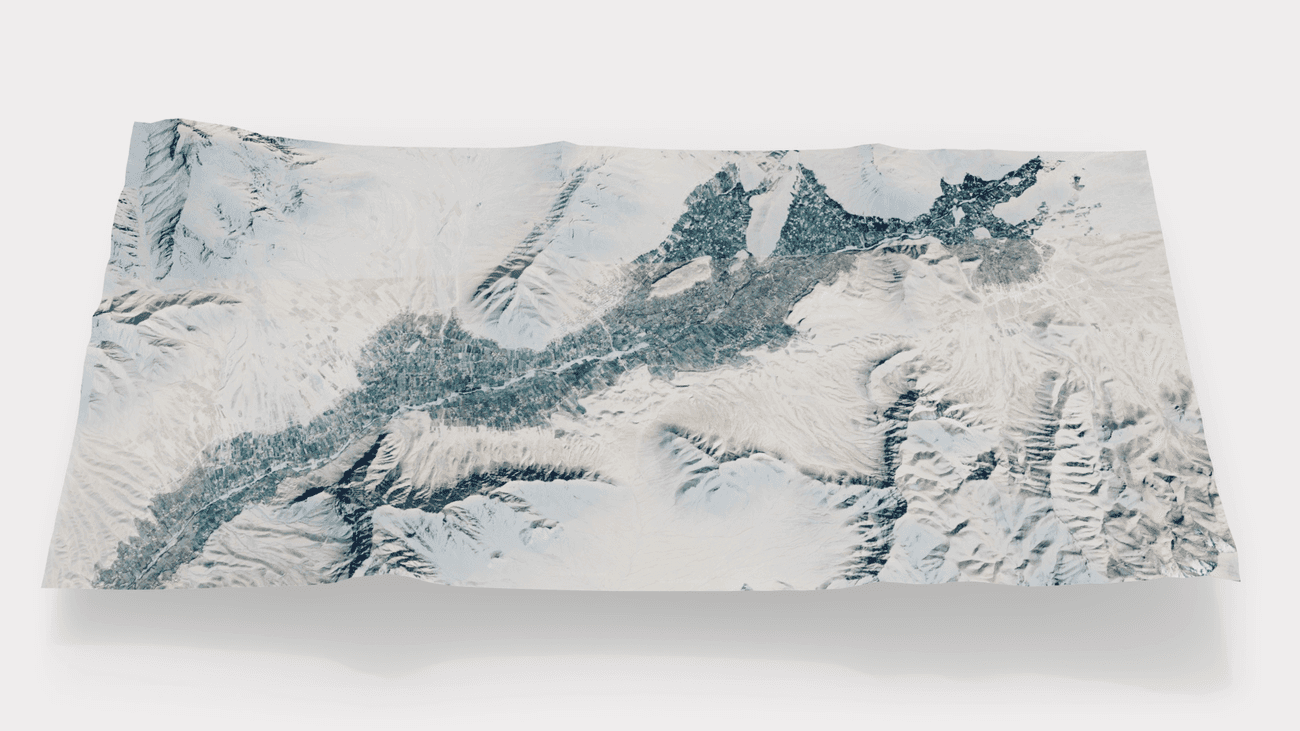

Quala 4131 is in Chora, a hilly, vegetated area in the southern Afghan province of Uruzgan. Tens of thousands of people live in the region, mostly working the land. In 2007 it was also a key battleground in the conflict between the NATO-led International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) and the Taliban.

After months of sporadic clashes, losing the area would have been a significant defeat for ISAF - which had a base in the regional capital Tarin Kot and multiple transport and logistics routes running through Chora.

For five months, the ISAF and allied Afghan forces had been preparing for an attack to claim full control of the region. 1,400 Dutch soldiers, along with troops from Australia and other countries, had been sent to the region as part of Task Force Uruzgan (TFU).

With Taliban fighters amassing in Chora, ISAF duty officers produce a map depicting the area.

To recreate the day's events, Airwars has matched that map with satellite imagery of the area.

The officers place a diamond near a village they have labelled Quala 4131 – indicating hostile forces in that location.

The map includes a faint grid, divided into vertical areas numbered from 18 to 25 – Quala 4131 lies on vertical 22.

Five hours later, Platoon 1.2 of the TFU moves west along a main road. They reach a ‘choke point’ – the southernmost part of a main road – around 300 metres from Quala 4131.

They are fired upon from a south-westerly direction by OMF (opposing military forces), not far from Quala 4131.

The forces advance along the road. The same platoon is fired upon by OMF using mortars.

The soldiers assess the fire to be coming from about 800 metres away, west of Quala 4131.

Half an hour later, the TFU fires on militants near the river running through the valley.

The site they target is about 400 metres to the east of Quala 4131.

At 20:00, the TFU commander, Colonel Hans van Griensven, decides that Chora should be held using “all necessary means.”

Later in court, this is referred to as the ‘stand and fight decision.’

Van Griensven calls for air power to strike Taliban targets identified earlier in the day, including those not directly observed.

In the next seven hours, there is no further confirmed Taliban activity in or around Quala 4131.

An engagement area drawn up earlier by the TFU was limited to west of vertical 21, where the majority of fire had come from in recent days. Quala 4131, on vertical 22, was outside this engagement area.

The TFU commander had asked local authorities, such as the district chief and the tribal leader of the areas around Chora, to evacuate civilians.

The TFU, working with local Afghan police, had encouraged civilians to move east of vertical 22.

Over two hours, F-16 fighter jets drop 28 bombs throughout Chora. Seven strike Quala 4131. A self-propelled artillery gun is also used.

The quala is bombed in three waves over 50 minutes, flattening the village.

In between each attack the residents run back into their now destroyed homes searching for survivors, while screaming at the warplanes above to stop.

At least 11 people died, including seven members of one family. At least four people were permanently injured. One resident, who was permanently paralyzed as he tried to leave his burning house, later became a claimant in the Dutch court case.Another claimant lost most of his family – including his wife, five of his children, and his daughter-in-law. The family’s land - including 600 fruit trees that sustained their livelihood - was decimated. Airwars has chosen not to name the claimants over security concerns.

Listen to a claimant’s testimony from the Dutch court case

How could they do this to us?

Were they here to help us or were they here to destroy us and to cause us damage?

They should have helped us and they should have protected our property and land.

They destroyed our property and land. They killed children, they killed women, they martyred and injured them.

Why has this happened to us?

The aftermath of the attack / Image released during Dutch court case

Estimates suggest that more than 45,000 Afghan civilians were killed between the 2001 US invasion and their ultimate withdrawal - and Taliban return - two decades later. They were killed in a myriad of different ways - American bombings, Taliban shootings, Afghan police raids. Yet they share one commonality - almost none of these deaths have led to accountability.

The bombing of Quala 4131 could have been yet another incident remembered only by those affected. But crucial early documentation, as well as the dedication of a lawyer and determination of the victims, helped ensure the families eventually got the answers they sought.

Eleven days after the attack

An After Action Report drawn up by TFU soldiers was sent to the Dutch Chief of Defence, explaining the attack on Quala 4131 as part of a wider four-day regional battle. It stated that “leaving CHORA was no option” as withdrawing would have undermined ISAF credibility - with the population of Chora suffering as a result.

This report contained logbooks of messages between TFU personnel. As with many other documents in this article, the logbooks were ultimately released during the Dutch court case. They demonstrated that other qualas were also destroyed on the morning of June 17th, despite the TFU recording the presence of civilians.

At 18:38 on June 16th, a Dutch soldier said an Afghan citizen in a quala had raised a flag in the hope that they would not be fired on again - and the man was taking injured family members to a medical clinic.

At 00:20 on June 17th, three hours before the attack on Quala 4131, a Dutch officer wrote that they were targeting “2 qualas, 1 extra” as well.

An hour later, a military spotter (JTAC) asked about another quala, which they argued should be “seized”.

The After Action Report concluded that “till now, there are no facts which prove that LNs [local nationals] died because of ISAF engagements.” A number of other qualas were also ‘engaged’, including those numbered 4022 and 4074.

Thirteen days after the attack

An ISAF Provincial Reconstruction Team recorded that they met with families from Quala 4131, noting that in addition to the human toll, the village had suffered the loss of several livestock - their key livelihood.

The officials appear to have made a payment to the surviving family members, demonstrating that they accepted the family’s civilian status. The Dutch Ministry of Defence confirmed to Airwars a payment had been made.

One month after the attack

A second After Action Review, also drawn up by TFU soldiers, was sent to the Dutch Chief of Defense.

It found no internal procedures were violated but concluded there was no ‘direct observation’ of the targets when the artillery gun was used. It concluded, for the first time, that there might not have been “sufficient distinction between military targets and civilian objects.”

The review concluded at least 120 civilians were killed or injured between June 15 and June 20. It asserted that militants fired on ISAF from qualas where residents were present – and admitted that even with the use of “precision air weapons,” retaliatory attacks on these villages likely harmed civilians.

One year after the attack

The Public Prosecution Service in the Netherlands announced they would not prosecute Dutch soldiers for their conduct during the Battle of Chora, concluding the force used was within the limits of international humanitarian law.

Three years after the attack

Connected through an intermediary, Liesbeth Zegveld, a prominent Dutch human rights lawyer at Prakken d'Oliveira, agreed to represent the surviving family members of Quala 4131. The family had already left what remained of their home.

Seven years after the attack

Zegveld largely lost touch with her clients for several years. Local telephone poles had been downed, meaning the claimants had to travel to a nearby city - an expensive, hours-long journey - to communicate with her. Often, a translator wasn't available when they were.

In 2014, the family returned to their home. As they readied their land for new growth, they picked bomb fragments out of the ground.

With the relative stability of their return, the family started to build a case with Zegveld.

The aftermath of the attack / Image released during Dutch court case

Thirteen years after the attack

The litigation began. The case was in a civil - rather than criminal - court, with the claimants pursuing compensation for the harm suffered through actions of ISAF - and specifically the Dutch forces.

The domestic court, which is the District Court of the Hague, did not typically rule on questions of international humanitarian law (IHL), but as the alleged tort violation took place during a conflict, IHL was applied. The claimants argued that one of the tenets of IHL, the principle of distinction - which requires all parties to a conflict to distinguish between civilian and military objects and act accordingly - was violated.

For the next two years, Zegveld, her clients and the state went back and forth.

The eventual ruling appears to have hinged on three crucial elements of the Dutch MoD's argument for bombing Quala 4131.

The first was that Quala 4131 was in a “strategically favourable” location for attacking the international forces, particularly due to the topography of the valley and its location near a ‘choke point‘ – although there were many other qualas along that river.

The second was that TFU Platoon 1.2 had been fired upon by the Taliban from the general direction of Quala 4131 at different points throughout June 16th. The court ultimately found that fire from the general direction of Quala 4131 could not be taken as confirmation that it had come from the quala itself.

Finally, and most importantly, the Dutch MoD argued that it must be assumed there was sufficient information to indicate Quala 4131 was an enemy firing point, as otherwise it wouldn’t have been hit. A post-mission report produced by one of the military spotters known as Joint Terminal Attack Controllers (JTAC) – a Dutch JTAC referred to as Windmill 68 – suggested that information on Quala 4131 as a hostile firing point had been gathered through “own ground troops in front.”

The former Chief Joint Fires of the Task Force Uruzgan, A.P. van Wijk, told the court that the JTAC for Quala 4131 was aware that it had been previously designated as an enemy firing position. Van Wijk also stated that late on the night of the 16th, new information came in from other sources which lead to the decision “to drop seven bombs on Quala 4131.” He argued that the decision to bomb this quala would never have been made solely on the basis of information more than 12 hours old.

Yet, over two years of proceedings, the Dutch military was unable to produce any evidence to substantiate this claim. In dozens of pages of logbooks, there was nothing to confirm that Quala 4131 was being used as a military site in the hours before the bombings.

The Dutch argued that this information must have been lost. Zegveld argued it likely never existed.

“[The Dutch] argued that there must have been intelligence to show that it was a military target, otherwise it wouldn’t have been attacked. Therefore, the fact it was attacked showed that it was a military target, which is getting the determination completely wrong,” said Lattimer, from the Ceasefire NGO. “If the court had accepted that, then there would have been motivations for militaries around the world to not keep any records.”

Fifteen years after the attack

On November 23, 2022, the court found that the state had acted unlawfully in bombing Quala 4131. It found the state could not prove it had evidence the quala was an enemy firing position and, as such, the bombing violated the principle of distinction under IHL. The Ministry of Defence had the opportunity to appeal the decision but ultimately decided against it.

Media coverage of the case and the subsequent ruling emphasised that this was a civil case and that ultimately it hinged on flawed military record-keeping. But advocates argue its significance was underplayed.

“This case, the fact that it happened and that these people’s claims were ‘put right,’ is wonderful in the sense that it’s been accomplished. But we should keep in mind that this is still the exception rather than the rule,” said Erin Bijl of PAX, a Netherlands-based peace advocacy organisation. “It’s quite rare internationally to see that there is a court case around NATO operations in Afghanistan, and there’s a lot of interest about what this actually means - for the Netherlands and also for potential military partners.”

In response to questions from Airwars, the Dutch Ministry of Defence said it had introduced a number of measures in recent years to improve the country’s tracking, mitigation, and transparency around issues of civilian harm. In 2020 the Ministry committed to new measures regarding “investigations into possible civilian casualties,” which were further developed in a “step-by-step approach concerning the subject of civilian casualties” in 2022, the MoD said.

Several other investigations into the Battle of Chora, the wider operation in which the bombing of Quala 4131 took place, have been carried out – including by NATO and the U.N. Assistance Mission in Afghanistan (UNAMA). Civil cases in active combat zones are difficult to push through; particularly as the crucial moments of decision-making are often interpreted in favour of the military.

“There is a tendency, particularly among military lawyers, to see everything according to the tests of criminal responsibility - that if no war crimes were committed then there was really no violation,” said Lattimer. “Here, you have a clear case that the court said, they weren't making a finding of a war crime, but that there was nonetheless a violation of IHL.”

Present day - Seventeen years after the attack

Zegveld, her team and the claimants are currently working out the logistics of reparations, which would likely mean the families are paid a sum. “They invested a lot of time, they were very patient with this case that had no immediate outcome,” said Zegveld. “They were very grateful – it was meaningful for them.”

Advocates argue the case sets a significant precedent – that civil litigation can still lead to some form of reparations, and justice, for victims many years later.

For Zegveld, the fact that the case ended up in court at all was “kind of coincidental… I like to do these cases, and the family were determined.”

“But as soon as you’ve passed this threshold into the courtroom, I think many more cases on Afghanistan could and should be won.”