A new analysis of Coalition reports shows that strike locations may be as many as 90 kilometers or more from where they are listed — a serious concern for investigators.

A version of this article is published by Bellingcat.

Christiaan Triebert is Airwars’ volunteer geolocator, helping us to determine coordinates for civilian casualty incidents. As an award-winning researcher at Bellingcat, he focuses on a variety of topics, including post-strike analysis of attacks like that on the mosque in al-Jinah.

Note: Hundreds of official videos showing airstrikes against targets of the so-called Islamic State (ISIL) in Syria and Iraq have recently been removed from the public YouTube channel of the Coalition. In a written statement to Bellingcat, the Coalition said higher-quality versions of the videos were being uploaded to DVIDS for “greater transparency and increased availability.” However, an initial assessment appears to show that not all videos have been migrated. Coalition offficials have also given a different account to Airwars in the past as to why the videos were removed, suggesting their presence on the official YouTube channel no longer matched strategic goals. Airwars is permanently archiving all known Coalition and CENTCOM videos issued since August 2014, to ensure their continued availability.

The publicly provided locations issued by the Coalition for its airstrikes in Iraq and Syria may be off by as much as 93 kilometers, according to a new and detailed analysis of released military videos. After 1,000 days of the anti-ISIL campaign, these disparities pose question marks for monitors attempting to understand where US and allied strikes took place, and then match them to civilian casualty reports from the ground. They also makes clear that Coalition casualty assessors would be unwise to use their own published reports as a guide to where airstrikes have actually taken place,

In its Transparency Audit of the Coalition, published in December 2016, Airwars noted problems with the public reporting process. Difficult to navigate internal logs “in turn led to quite vague military reporting.” Locations, then, could only be taken as approximate. One CENTCOM senior official explained the situation in some detail:

“When the aircrew come back [from a strike mission], as you drill into a geographic location, some of those areas have towns that consist of three or four people. So typically what’s going to be in the strike log is going to be the largest city nearby. And they’ll annotate, ‘Conducted a strike near Mosul.’ In fact it’s going to be some small town that’s 23 clicks [kilometers] outside of Mosul. If they put that on the strike log, once it goes through the ‘Enterprise’ [slang for the Combined Air Operations Centre] no one knows where that is.”

Officials were keen to stress that if an incident was being investigated, “we do have the ability to go back and drill down into the detail.”

200 videos

While earlier videos were posted by CENTCOM, the first video depicting an airstrike was uploaded to the Coalition’s own official Youtube channel on April 11, 2015. Over 200 airstrike videos followed over nearly two years. By far the majority (around 68% as of April 24, 2017) of Coalition airstrikes have been conducted by the US. Airstrike videos are also disseminated through other channels, such as the ministries of defence of Coalition members, including the British, the French, the Jordanians, and the Iraqis.

Additionally, at least one US Navy air squadron had also uploaded videos separately to their own YouTube channel (since taken down.) While Bellingcat has crowdsourcing projects running for those specific MoD videos as well, they are not included in this analysis.

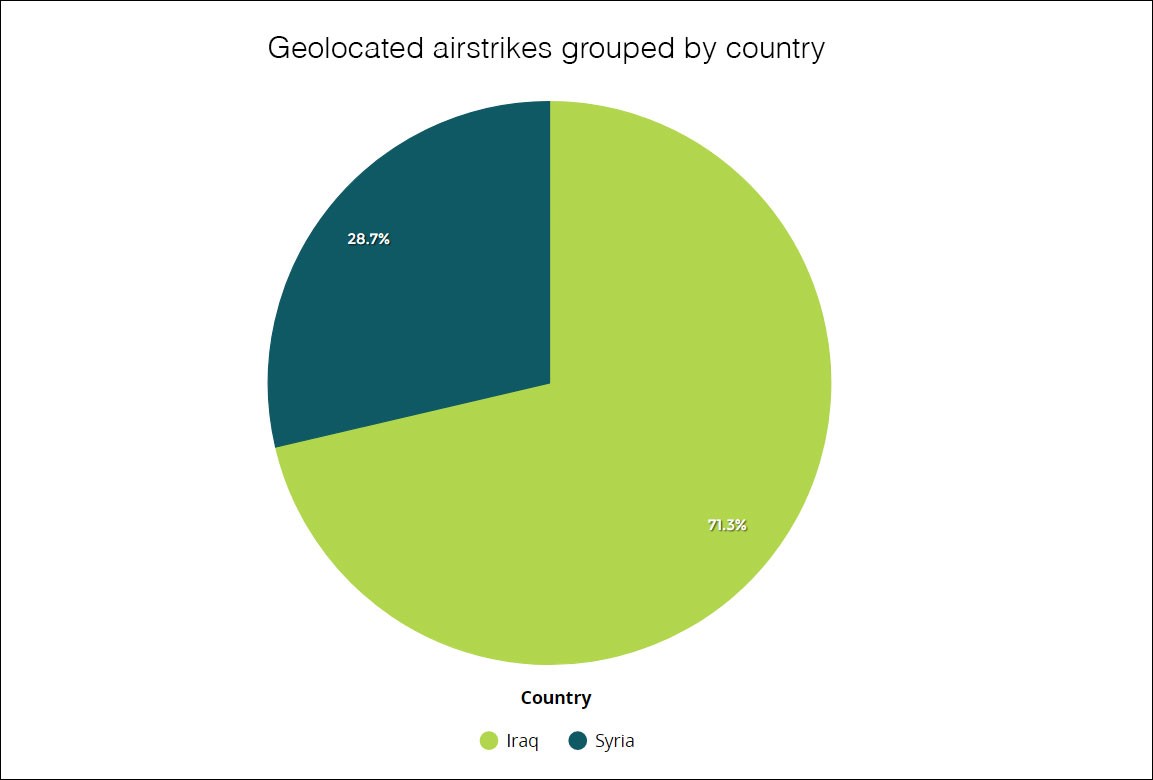

So far, 67 percent of the airstrikes shown in the Coalition airstrike videos have been successfully geolocated. You can access all Bellingcat data, which will be updated as soon as there are new geolocations, including from DVIDS HUB, on Silk. Bellingcat used Meedan’s Check platform to geolocate the videos, and the project is open to everyone to join By far most of the strikes shown in videos uploaded to YouTube (as of April 28, 2017) were geolocated to Iraq.

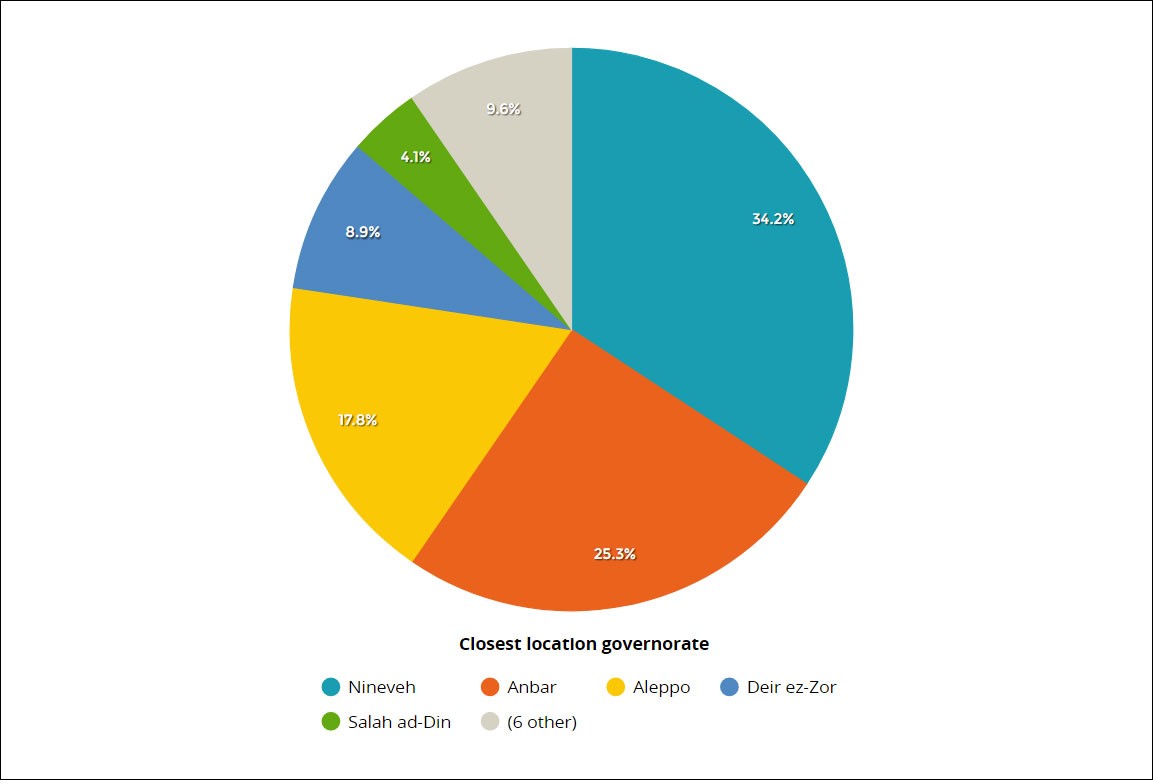

Broken down by provinces, the highest number of airstrikes were geolocated to the Iraqi governorates of Nineveh and Anbar, followed by the Syrian governorate of Aleppo, as of April 28, 2017.

Generally, the Coalition gives an indication of a geographical location by labeling the videos “near [location X]”. There are only a handful of videos that do not contain the word “near” but simply mention a location. This analysis considers “near” as being within a 10 km range of the claimed location and a label is considered “accurate” when it falls within that range. Of all geolocated videos, 68 percent were determined to be accurate. Videos outside of the 10 km range strayed up to around 93 km of the claimed location, and for one video no location approximation was given.

Many of the videos with a significant distance from the claimed location are oil-related facilities that are indeed ‘near’ Deir ez-Zor or Al-Bukamal, such as an oil separation facility at the Al-Ahmar oil field. In a desert with few or no settled areas nearby, these location claims may still be considered relatively accurate.

However, there are other incidents that appear to be less concisely located. Perhaps the most concerning incident of all the geolocated videos was a strike on an IS “concealed tactical vehicle” that was claimed to have been conducted on March 23, 2015, which was labelled as “near Al Hawl”, a town in north-eastern Syria. However, the targeted building has been successfully geolocated to a building in Jayar Ghalfas, a town in northwest Iraq.

A screenshot from a Coalition video claiming to show an airstrike on an IS ‘concealed tactical vehicle’ near Al-Hawl, a town in eastern Syria. The building was geolocated to Jayar Ghalfas, a town in northwest Iraq, as the Microsoft Bing satellite imagery (36.137411, 41.297414) on the right shows. The location is around 30 km southwest of Al-Hawl.

Though this video was labelled as being in a different country than where it actually took place, it is still relatively near Al-Hawl — around 30 km away.

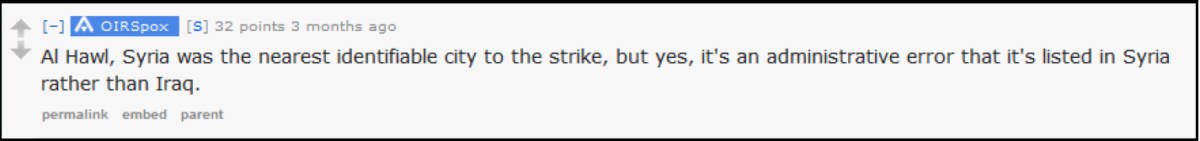

When Col. Steve Warren, at the time the Coalition’s spokesperson, gave an “Ask Me Anything” on the social media and news aggregation website Reddit, this author asked him about this particular incident. Col. Warren replied that this was “an administrative error that it’s listed as Syria rather than Iraq”, explaining that Al-Hawl in Syria “was the nearest identifiable city to the strike.”

The reply by Col. Warren, the Coalition’s spokesperson on the question why it was labelled near to a town in Syria but showed a location in Iraq.

More recently, the US erred in its labelling once more, when a controversial strike on a group of individuals gathered in a mosque in Al-Jinah, Syria, was initially labelled as being in the Idlib governorate. While close, the building was actually in nearby Aleppo governorate. This strike was not an official Coalition attack – and was instead the United States unilaterally targeting alleged al Qaeda fighters. The US carries out nearly all of the alliance’s anti-ISIL bombings in Syria, and military assets can be used for both campaigns.

When asked for clarification about this incident, a CENTCOM spokesperson told Bellingcat that they “don’t mean to cause any confusion. Different internal reports may have listed this differently.”

The Coalition thus seems to use a limited number of labels for their targeted location areas. The “Al Hawl, Syria” label was probably closer than their nearest other Iraqi location label, “Sinjar”, around 50 km northeast of Jayar Ghalfas.

The Coalition’s ‘region’ labels

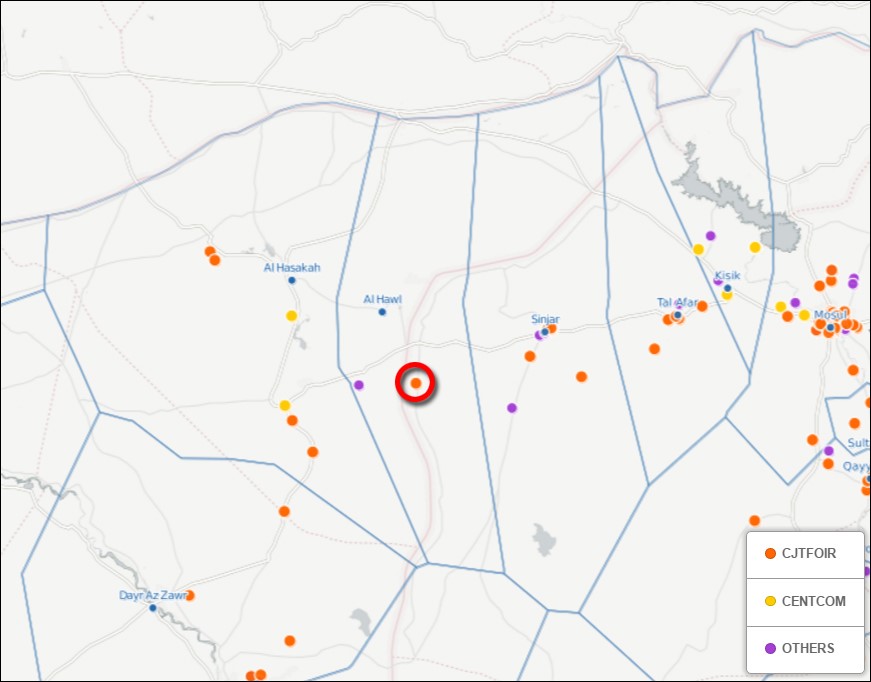

Which region does the Coalition use to label one airstrike as “near Mosul” but the other one as “near Al Hawl”? To get a better insight in which regions are used by the Coalition, the geolocator @obretix mapped all geolocated airstrike videos, and then used a Voronoi diagram – which is a partitioning of a plane into regions based on distance to points in a specific subset of the plane. In this case, the points are thus all “near” locations mentioned by the Coalition. The geolocations are then corresponding to a region that is closer than any other point.

As the following image shows, Al-Hawl is indeed the closest location to the target struck by the Coalition (circled in red) in the number of areas the Coalition has used.

An excerpt from a Voronoi diagram of an impression of the regions used by the Coalition, based on the geolocated videos. The geolocated airstrike of March 23, 2016 that was labelled near ‘Al Hawl’ is circled in red. Map by @obretix

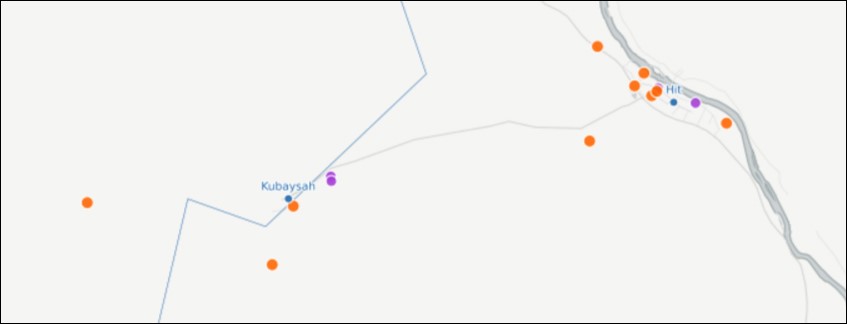

There are more interesting insights the maps reveals. While the Coalition does use a label for “near Kubaysah”, a city in Iraq, some strikes within the city’s perimeters were labelled as “near Hit” — a city nearby but still less accurate than using a label there was for that city.

A detailed view on the Kubaysah/Hit region on the Voronoi diagram map, showing that two videos labelled as “near Hit” were in fact closer to Kubaysah, which also has its own ‘location label’.

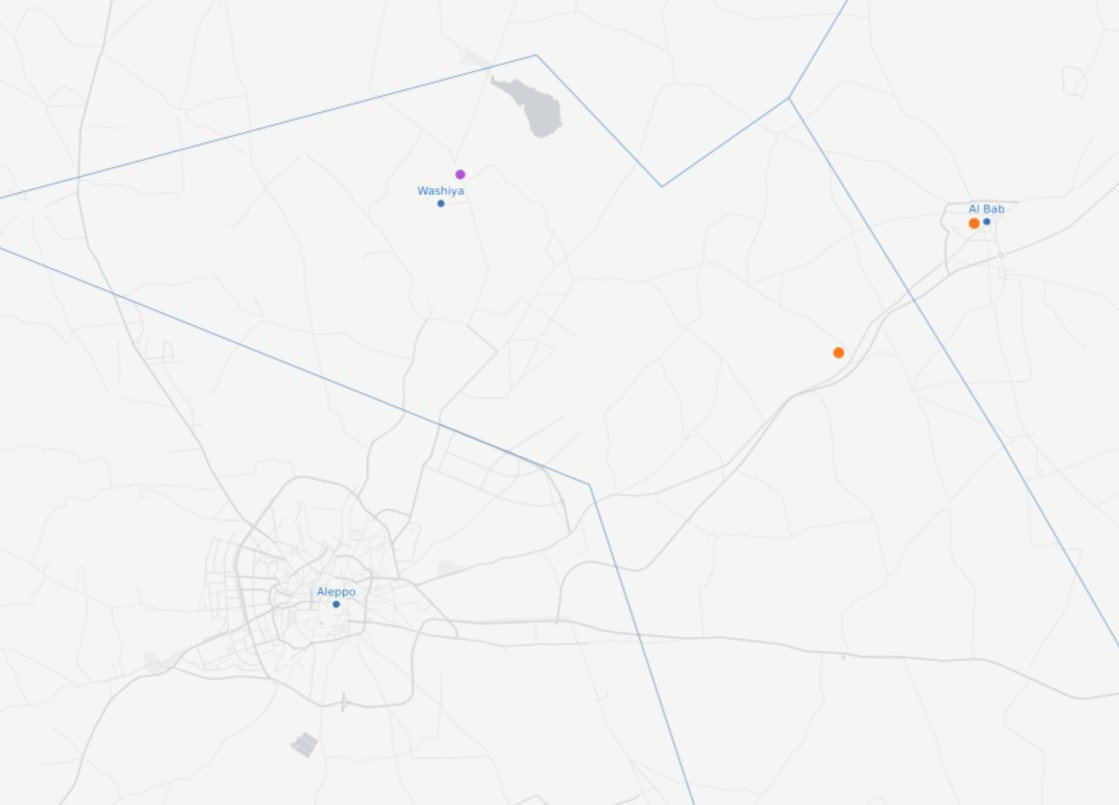

Another example of remarkable region labels is the use of hamlets, such as “near Washiya” and “near Sultan Abdullah” – places with only a few houses. but close to respectively Aleppo and Mosul. “Near Aleppo” is not used in any of the YouTube videos, while “near Washiya” has been twice for a target only a double dozen kilometres away from Aleppo city. Why would these small hamlets be used as a region label, while the case of Jayar Ghalfas could not get its own region label? Is this intentional? This is a question that remains unanswered.

Overall, all location claims were all within 100 km distance of the claimed location, and all of these claims were relatively accurate as to the location it referred to — unlike the Russian airstrike videos, which were in some cases massively inaccurate.

A detailed view of the area around Aleppo city in Syria. A video close to Aleppo was not tagged as “near Aleppo” but “near Washiya” (orange dot), a tiny hamlet in the northern countryside

Civilian Casualties

It is possible that civilian casualties take place in a portion of these videos. Some, such as the video of airstrikes on the University of Mosul in March 2016, may in fact show airstrikes that caused significant civilian casualties.

Perhaps the most striking example of a video showing civilian casualties came from an airstrike on September 20th-21st, 2015, targeting an IS “VBIED network” according to the Coalition at the time. The video – which showed a structure destroyed by an explosion – was deleted after questions were raised, but was archived and re-uploaded by others, including investigative journalist Azmat Khan.

But was this really a “VBIED network”? Under the original upload, a commenter posted that the structures shown were his family’s home in Mosul.

“I will NEVER forget my innocent and dear cousins who died in this pointless airstrike. Do you really know who these people were? They were innocent and happy family members of mine.”

Days after the strike Dr Zareena Grewal, a relative living in the US wrote in the New York Times that four members of the Rezzo family had died in the strike. On April 2nd 2017 – 588 days later – the Coalition finally admitted that it indeed bombed a family home which it had confused with an ISIL headquarters.

“The case was brought to our attention by the media and we discovered the oversight, relooked [at] the case based on the information provided by the journalist and family, which confirmed the 2015 assessment,” Colonel Joe Scrocca, Director of Public Affairs for the Coalition told Airwars.

Even though the published strike video actually depicted the unseen killing of a family, it remained – wrongly captioned – on the official Coalition YouTube channel for more than a year.

It is worth mentioning that all of the targets in the Coalition’s videos appear to be ‘clean’ objects like vehicles, factories and fighting positions. It almost looks like video game, just like IS’s propaganda videos of suicide vehicle-borne improvised explosive devices (SVBIEDs). The Coalition’s videos appear only to showcase the precision and efficiency of Coalition bombs and missiles. They rarely show people, let alone victims.