Somalia has seen a prolonged period of instability, resulting largely from the actions of insurgent group Al-Shabab. U.S. forces have been active in Somalia since 2007, supporting the Somali government in its campaign against Al-Shabab, as well as conducting drone strikes on other terrorist groups.

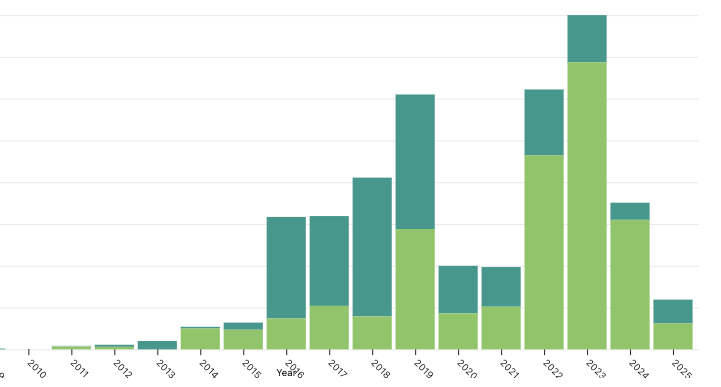

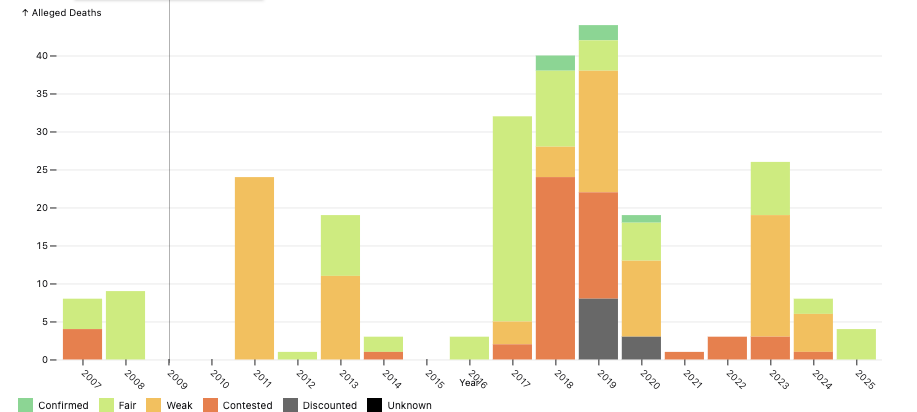

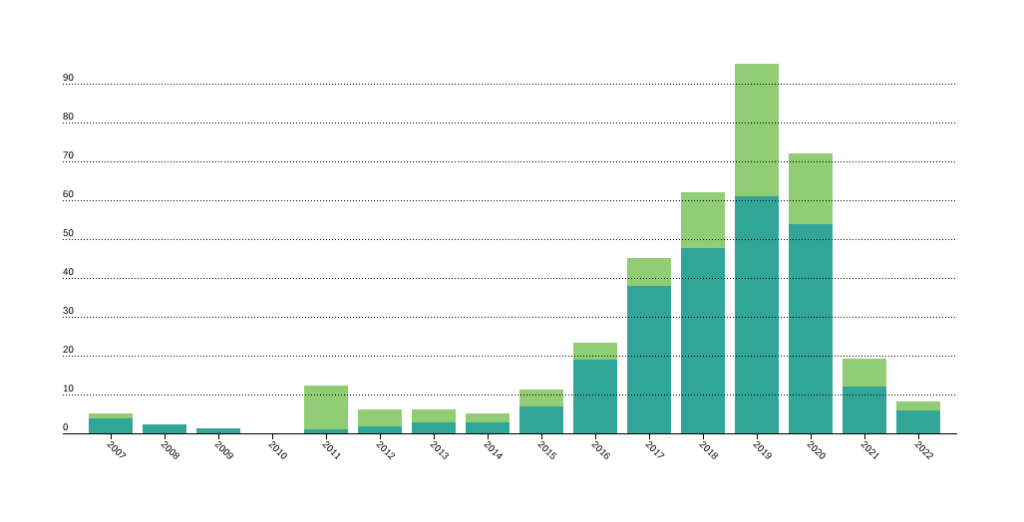

Airwars has documented allegations of U.S. strikes in Somalia since 2007, as well as airstrikes from other international forces since 2024. Airwars is the custodian of a database produced by The Bureau of Investigative Journalism on covert U.S. operations between 2007 and 2019.

Conflicts monitored involving Somalia