Iraqi forces supported by the international Coalition have driven so-called Islamic State from the nation’s cities and towns. The cost in lives has been significant.

When Iraqi Prime Minister Haider al Abadi announced victory over so-called Islamic State in Iraq on December 9th, his allies in the international Coalition had just begun their 40th month of bombing ISIS targets in the beleaguered nation. A grinding territorial war was finally ending.

“Our forces fully control the Iraqi-Syrian border, and thus we can announce the end of the war against Daesh,” Abadi said, referring to the group by an Arabic acronym. “Our battle was with the enemy that wanted to kill our civilization, but we have won with our unity and determination.”

As Iraqi forces celebrated in Baghdad with a military parade, the Coalition congratulated Iraqis on the defeat of their common enemy – while the US pledged its continued backing of Baghdad. With ISIS now losing all major territorial footholds in the country, the toll of the occupation – and from the internationally supported campaign to remove the terror group from Iraq – are still being measured.

Estimates of how many have died since ISIS began its blitz across northern and western Iraq in 2014 remain fragmentary. Thousands of civilians were killed, disappeared or were captured and enslaved, as ISIS fighters targeted minority groups like the Yazidis — crimes that a UN Commission of Inquiry would later label genocidal.

“The public statements and conduct of ISIS and its fighters clearly demonstrate that ISIS intended to destroy the Yazidis of Sinjar, composing the majority of the world’s Yazidi population, in whole or in part,” concluded the commission.

A Yazidi boy – his face and hair matted with dust – re-enters Iraq from Syria, at a border crossing in the town of Peshkhabour in Dohuk Governorate. Photo: UNICEF/Wathiq Khuzaie

When they weren’t shooting civilians, ISIS often trapped them in their homes as Iraq’s cities and towns came under assault — at times even welding them inside. Mines and improvised explosives were widely dispersed in homes and in the street. These will likely kill Iraqis for years to come. The Coalition recently reported that it has so far helped remove “nearly 40,000 kilograms of explosives since April 2016 from liberated areas in Iraq.”

Thousands of captured Iraqi soldiers and police officers were also murdered during the early stages of the occupation, their executions shown in graphic ISIS propaganda videos. During recent operations to capture Mosul, the UN estimates that at least 741 civilians were summarily executed by ISIS fighters, with hundreds more killed by the groups’ artillery and vehicle bombs. Mass graves are still being found.

“There are many layers of the dead in and around Mosul,” said Katharina Ritz, head of delegation for the ICRC in Iraq. “From different stages of this latest conflict, such as the discovery of many mass graves reportedly linked to ISIS rule, to those who died in various ways during the assault, and those who died at the end and were buried under rubble.”

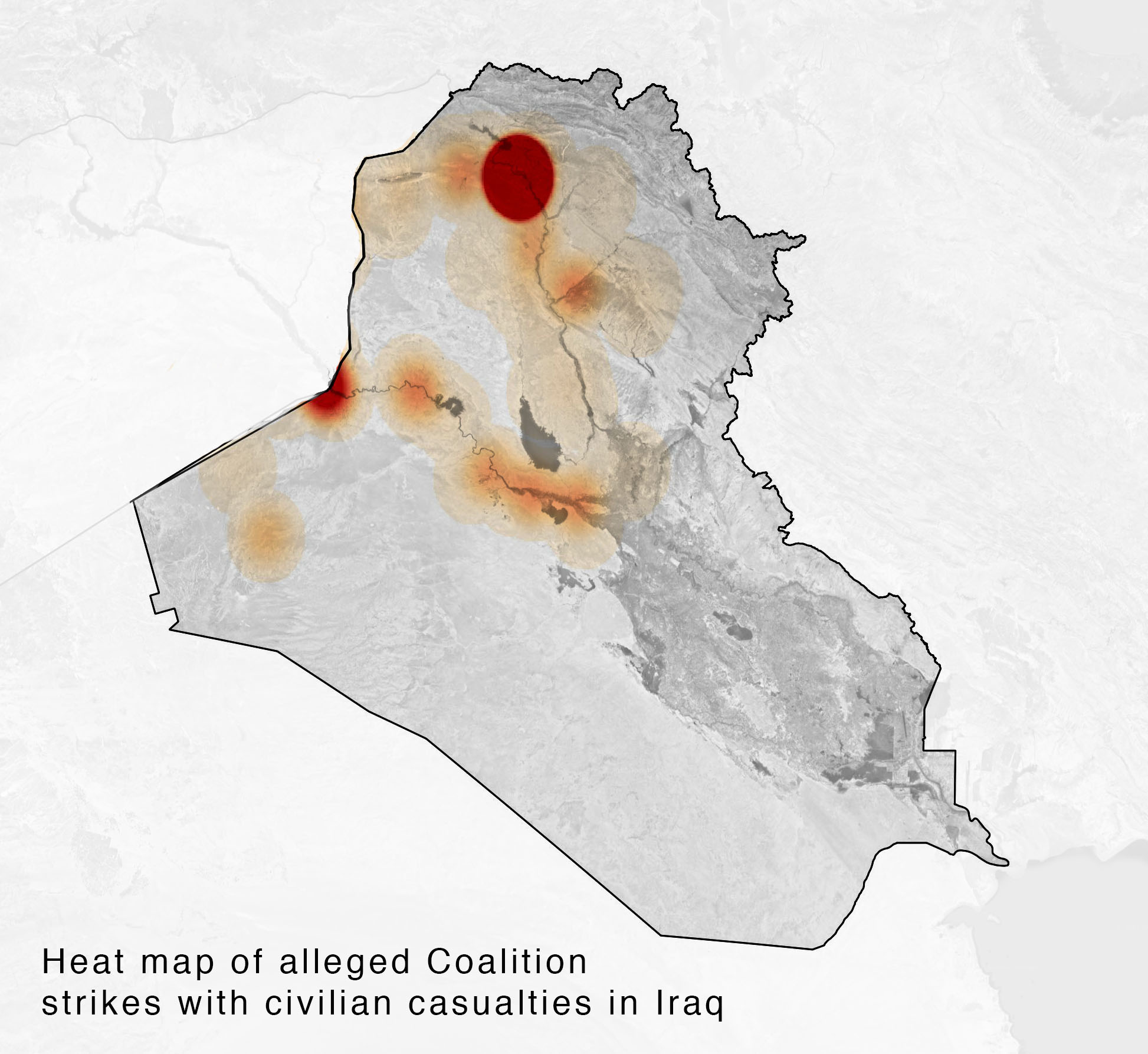

The heat map shows the locations of alleged Coalition strikes resulting in civilian casualties in Iraq (via the Airwars database) throughout the war. The intensity of colour shows where most claims have been reported. The largest dot represents Mosul.

Iraqis bore brunt of military cost

Ground fighters on all sides of the conflict in Iraq suffered heavy casualties. US military officials have thrown around large numbers — claiming anywhere from 45,000 to 70,000 or more ISIS fighters killed since Coalition operations began. But analysts have questioned whether the number of ISIS fighters in general has tended to be exaggerated, especially by Western militaries.

In the fight for Mosul, elite units like Iraq’s Special Operations Forces were so heavily depleted during fighting — by some estimates they suffered “upwards of 50 percent casualties” in East Mosul — that their role in the more densely packed West was severely diminished.

In March, CENTCOM chief Gen. Joseph Votel said that 774 Iraqi troops had so far been killed in Mosul. US officials have since put the number of Iraqi military dead in Mosul at 1,400. Other estimates place the number even higher: In November 2016, the UN reported that 1,959 members of the Iraqi Security Forces and supporting forces had been killed that month alone in Iraq. After the Iraqi government protested, the UN stopped publishing estimates of government forces killed in the fighting. Many more Peshmerga fighters and irregulars with Popular Mobilization Forces militias also died fighting ISIS.

Partly as a result of this high Iraqi toll, in December 2016 the Obama administration loosened restrictions on who could call in airstrikes, allowing personnel farther down the command chain to do so. That decision allowed faster approval of attacks, which Coalition officials said would help assist ground troops.

However some journalists on the ground have said that this led to an immediate rise in civilian casualties, a toll that only grew as operations in Mosul continued into the city’s West and ultimately ended in a hellish assault on the narrowly packed Old City.

Though civilians, Iraqi forces and members of ISIS were killed in significant numbers, remarkably few Coalition personnel have died during combat operations – a measure not just of battlefield superiority but of how intensively the alliance depended upon remote air and artillery strikes. As of December 15th, just 13 US service members were reported as killed in action during the entirety of Coalition operations in Iraq and Syria going back to 2014. Partners like France have only suffered rare casualties during operations around Mosul, and not from direct fighting.

There are few conflicts in the history of warfare where a force’s own ability to destroy an enemy over extended periods has been matched by their own relative safety from harm. By comparison, partner forces on the ground suffered casualties at hundreds of times the rate of the Coalition’s.

A heavy civilian toll

In contrast with high Coalition tallies of ISIS fighters killed, estimates of civilian deaths have been treated conservatively by belligerents and, in many cases, by the media. The air campaign against ISIS began in Iraq on August 8th 2014, when US jets bombed targets as part of an effort to stave off the terror group’s attempt to capture, enslave or exterminate fleeing Yezidis in northern Iraq. By then, the extremist group had already captured large areas of Western and Northern Iraqi, including Iraq’s second city Mosul.

Eight days into the US intervention the first civilian casualties tied to US strikes were alleged. On August 16th outlets including the German press agency DPA and Al Jazeera reported that 11 civilians had been killed in Sinjar. According to local accounts, munitions aimed at fleeing ISIS fighters had instead hit civilian homes in the area. More than three years on, the Coalition has yet to assess this first claim – one of hundreds of Iraq allegations so far unaddressed by the US-led alliance.

It wasn’t until November 20th 2015 that the US first admitted responsibility for any civilian deaths in Iraq. Initially, the US said four civilians had been killed in a March 13th strike in Hatra that same year. Not publicly reported at the time, the incident was brought to the attention of the Coalition by the owner of one of two cars bombed near an ISIS checkpoint. After a Washington Post investigation, CENTCOM raised its estimate of civilians killed to 11. Among the dead were five children and four women. A redacted investigation was posted online by CENTCOM — a practice neither the US or Coalition would continue. Links to the original investigation have now been removed.

Out of some 800 local allegations against the Coalition in Iraq which have been identified by Airwars, the alliance has so far confirmed responsibility in 107 incidents – conceding a minimum of 471 civilian deaths and 97 injuries.

Eighty additional civilian deaths have been confirmed by the Coalition in unidentified events which were the result of non-US Coalition actions — strikes which could have taken place in either Iraq or Syria. America’s allies still refuse to accept responsibility for any of those 80 deaths.

Based on available public evidence, Airwars researchers currently assess 180 further incidents as likely the responsibility of the Coalition. The present Airwars estimate of the total number of civilians killed across all 287 events is between and 2,129 and 3,152 non-combatants.

Beyond the Coalition’s much lower estimates of how many civilians were killed due to its own strikes, the UN in Iraq has released only minimum figures for estimated civilian deaths which they acknowledge to be far below the true toll. In the case of one key province – Anbar – where much of the recent fighting has occurred, the UN has rarely offerted any casualty data. In its most recent monthly report, UNAMI, said it had once again been unable to obtain casualty figures for the province at all.

Only one group, Iraq Body Count, has attempted to systematically capture the death toll caused by all parties in Iraq since before ISIS first began its expansion. From January 2014 – when ISIS captured Fallujah – Iraq Body Count has recorded more than 66,000 civilians having been reported killed in violence throughout Iraq. Their monitoring has led to a preliminary count of 9,791 deaths during operations to recapture Mosul. Clarifying and unraveling reports will still take time, said Iraq Body Count co-founder Hamit Dardagan, who also works as the organisation’s principal analyst.

“After ISIS’s ousting we have a range of reports of mass graves of different age, and disentangling all these will take a lot of time, especially in relation to the more immediate reports that appeared and may in some cases have concerned the same victims,” said Dardagan. “The same need to disentangle multiple accounts of aggregate deaths holds true for OIR and Mosul. We have seen the official accounts, as you will have, but one wonders how even they could be near-finished as yet.”

Possible under-reporting of civilian harm

While there is little dispute that many thousands of Iraq civilians died in the past 42 months of war, understanding how non-combatants met their deaths often remains a significant challenge.

The Iraqi military has so far issued no estimates of the civilians killed by its own operations. The tally from ISIS killings, while likely running into many thousands, remains to be fully assessed.

The total number of deaths locally alleged from Coalition actions in Iraq between August 16th, 2014 and December 5th 2017 ranges from 9,736 to 13,972 civilians killed in 800 claimed events – though Airwars currently assesses the likely minimum tally at between 2,129 and 3,152 civilians killed, based on available reports.

In 276 cases, Airwars researchers were not able to determine who carried out the reported strike, and these remain labelled as ‘contested.’ Most of these incidents took place in 2017, predominantly in Mosul. This ambiguity in monitoring reflected an increasingly chaotic situation in the final year of fighting.

There are also worrying indicators that civilian casualties in Iraq from all military actions may have significantly been under-reported. Just over half of all admitted Coalition events in the country were never publicly reported at the time – we only know about these civilian harm incidents because Coalition pilots and analysts internally flagged concerns.

In addition, while the number of Coalition strikes overall in Iraq and Syria were roughly equal, Airwars has tracked almost twice the number of confirmed and likely civilian deaths from Coalition actions in Syria (3,823) than it has for Iraq (2,129). That disparity is thought to be linked to the far poorer local quality of civilian casualty reporting by NGOs and media within Iraq. How many more casualties were never reported we cannot know.

“Civil society groups are much better developed in Syria, after six years of war. Many have undergone extensive training in Turkey and have become expert at documenting violations,” said Benjamin Walsby, Middle East researcher at Amnesty International. “Generally speaking, Iraqi groups were not as well developed as their Syrian counterparts.”

Because of this gap in consistent monitoring – and the Coalition’s own lower estimates – the individual investigations of journalists and human rights workers like Walsby have played a key role in better understanding the toll of the war. In November, journalists Azmat Khan and Anand Gopal, writing in the New York Times, estimated that based on a field study of attacks in Northern Iraq, the actual toll of Coalition strikes in certain areas could be upwards of 30 times what has been publicly acknowledged.

The destruction of cities

The number of bombs and missiles unleashed on both Iraq and Syria rose considerably as the fighting escalated. Figures for munitions released by Iraqi forces have not been issued so far, while ISIS bragged of deploying hundreds of vehicle borne car bombs during the fighting. An average of five VBIED attacks were faced daily by Iraqi forces during fighting in East Mosul.

Accorded to US Air Force figures, the number of weapons released from aircraft under Coalition control rose from 6,292 in 2014 to 38,993 during the first 11 months of 2017. However, these figures exclude fire from Coalition helicopters, and ground based sources like artillery and HIMARS rockets. According to Coalition figures provided to Airwars, the number of munitions fired into Mosul during the 9-month battle to liberate the city exceeded 29,000. France alone reported more than 1,200 artillery strikes on Mosul.

The fighting has left swaths of urban areas in ruins, often the result of Coalition and Iraqi airstrikes and artillery fire into areas where ISIS proved difficult to dislodge. In the battle for Ramadi, where elite counterterror forces were back by heavy Coalition and Iraqi aerial support, UN analysis of satellite imagery showed more than 5,600 structures were damaged, nearly 2,000 of them destroyed.

A graphic produced by the United Nations showed damage to buildings in Ramadi.

Particularly damaging in the fight for Mosul were improvised rockets, hurled into the Old City by Iraqi forces. “The scale of death and destruction wrought upon Mosul and other parts of Iraq is almost unfathomable,” said Walsby, “Much of this was caused by Coalition airstrikes and Iraqi forces’ use of rocket assisted artillery, among other tactics. Fighting IS was difficult, but there were many things that Coalition forces and their Iraqi partners could and should have done differently to prioritise protection of civilians.”

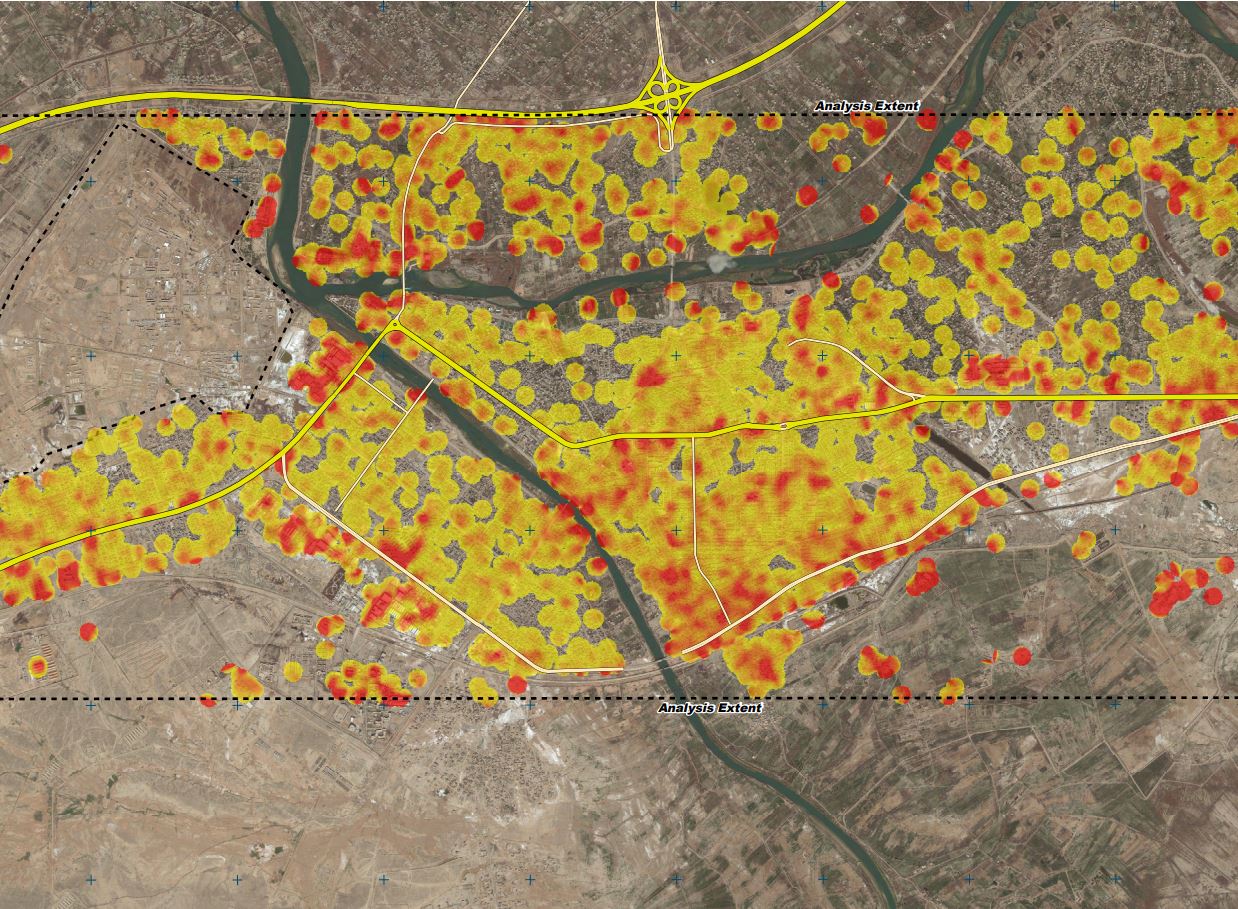

In total, Airwars presently estimates that between 1,066 and 1,579 civilians were likely killed by Coalition strikes in the vicinity of Mosul between October 17th and mid July. However this may represent a significant under-reporting, with a determination of responsibility presently impossible in many further cases. Overall, researchers monitored between 6,320 and 8,901 alleged civilian deaths in which the Coalition might have been imnplicated – with thousands more ISIS fighters and Iraqi ground troops also killed.

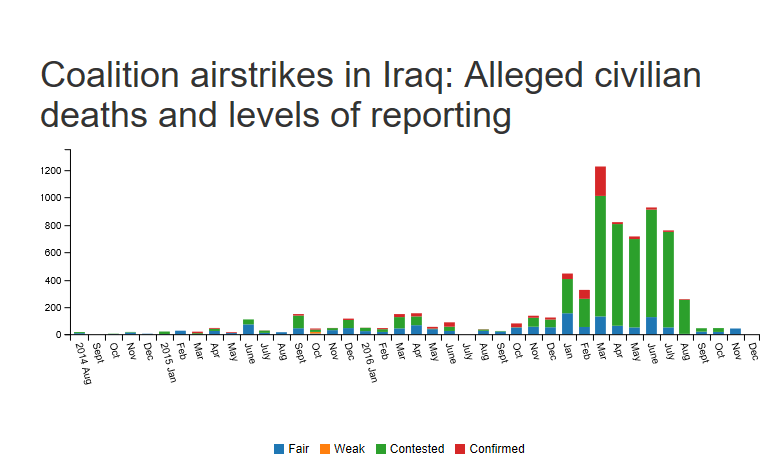

As this Airwars chart shows, reported civilian deaths in Iraq rose dramatically in 2017, reaching peak levels in March with the battle for West Mosul.

The limits of precision warfare

The deadliest strike admitted to by the Coalition across Iraq and Syria took place on March 17th 2017, in the al Jadida neighborhood of West Mosul. At least 105 civilians were killed when the Coalition dropped two 500-pound bombs which targeted snipers on the roof of the building. American officials claimed the house was rigged to explode, though locals have maintained that was not the case.

Though US and Coalition officials have insisted the anti-ISIS operation has been the most “precise air campaign in the history of warfare”, its undeniable physical and lethal toll has shown certain limits to high-tech warfare as it is currently being fought in urban areas.

Too often during the fighting in Raqqa and Mosul, heavy air and artillery strikes were used to clear buildings of ISIS fighters where the immediate presence of civilians appeared to be unknown.

“There’s no doubt that the technology is advanced and we can put rounds in places where we’ve never been able to before, but in urban environments the enemy can turn every building, every room into fortified positions you are taking out infrastructure and you are taking out civilians if they are in what the enemy wants to be a part of,” said John Spencer, a former army infantryman and deputy director of the Modern War Institute at West Point.

“If we know that the character of warfare has changed, and the people that want power figure out that’s where they get the most advantage, we should be adapting.”

While the overall civilian casualty toll has been relatively high, perhaps more remarkable was the number of Iraqis who were able to escape the fighting – despite the intensity of battle. Through October 31st of this year, 3,173,088 Iraqis had been displaced by fighting across the country according to the UN. 2,624,430 had returned to where they were previously displaced from. Through October 18th, 793,422 people had been displaced from Mosul, and 300,576 had so far returned to their homes.

A lack of allied accountability

In an apparent effort to improve transparency among its Coalition partners, in April 2017 the US ceased identifying its own strike numbers in Iraq and Syria. However, based on earlier modelling and military reports from other countries, the US clearly carried out the vast majority of actions — well upwards of 90% in Syria.

In Iraq (where the Baghdad government invited the Coalition and its members to operate) non-US partner nations played a larger role – responsible for about one third of all Coalition airstrikes. As of December 1st 2017, the UK had launched the most strikes in Iraq of any ally, with 1,357 reported. It was closely followed by France – which declared 1,265 airstrikes and more than 1,100 artillery actions. Australia conducted approximately 600 strikes; the Netherlands 490; Denmark 258; Belgium 370 and Canada some 246 airstrikes.

With the exception of Australia, no Coalition member besides the US has admitted to a single civilian casualty in more than three years of war. This remains true despite an Airwars investigation that revealed in May 2017 that the US military had determined that at least 80 civilian deaths were the responsibility of other Coalition members. Even now, those deaths remain unclaimed by any nation. Family members of most victims of Coalition strikes in Iraq still cannot know what country was responsible for those deaths.

Key improvements in civilian casualty monitoring were introduced by the Coalition during the war – including the move to regular monthly casualty reports; a significant expansion of the alliance’s CIVCAS cell; the regular releasing of assessment co-ordinates; and the Coalition’s engagement with external agencies such as Airwars. Even so, more than half of the alleged casualty events tracked during the war have yet to be assessed – and it remains unclear how committed the Coalition allies will be to properly investigating this backlog as the ‘hot’ war ends.

An uncertain future

The war to defeat ISIS as a territorial entity in Iraq had the backing of the United Nations and the international community – and the active support of more than 70 nations. “The military victory over ISIS must be applauded,” said Sahr Muhammedally, Middle East and North Africa director at CIVIC. “Now comes the harder part for the Iraqi government and anti-ISIS coalition to restore critical infrastructure destroyed during operations; and clear buildings and roads of booby traps so people can return home safely. There must also be a robust presence of properly trained security forces to provide security and prevent revenge attacks against returning civilians.”

Like Syria, Iraq is not a member of the International Criminal Court, meaning that even ISIS’s crimes there do not fall under its jurisdiction. While the UN Human Rights Council has created a Commission of Inquiry for Syria, it has not yet done so for Iraq.

This September, however, the UN Security Council authorized a probe of ISIS’s crimes in Iraq which will preserve evidence for eventual criminal prosecution. Groups like Human Rights Watch criticized the move for falling short of a mandate to consider all crimes allegedly committed during the fighting, including by Iraqi, Kurdish and Coalition forces.

“ISIS drew worldwide condemnation and generated widespread publicity. It had to be defeated; we are all too aware of its unspeakable crimes,” said Amnesty’s Walsby. “What is yet to be properly acknowledged is the terrible price that thousands of Iraqi civilians paid for their liberation, at the hands of Iraqi and Coalition forces. Any victory statement that fails to acknowledge this is both deeply flawed and could prove short lived.”

“The challenges in Iraq after ISIS are many, but ensuring that all Iraqis are protected from harm and their losses dignified and recognized is essential to build the foundation for stability and reconciliation in Iraq,” said Muhammedally.

—–

Note: Since our report was posted, two important stories were published December 20th by the Associated Press and NPR, concerning the civilian toll in Mosul.

After an extensive investigation involving on the ground interviews, local morgue reports and reference to NGO databases – including Airwars’ – the AP determined that between 9,000 and 11,000 Mosul residents died during the 9-month assault on the city. Their analysis showed that roughly one third of those deaths were the responsibility of US-led Coalition or Iraqi forces. The likely civilian toll from morgue records “tracks closely with numbers gathered during the battle itself by Airwars and others,” wrote the authors of the AP report.

Based on figures obtained from the Mosul morgue, NPR put the number of civilians killed in the city at “over 5,000.” That number, NPR noted, “is likely more than the number of ISIS fighters believed to have been in Mosul and presumed dead.”