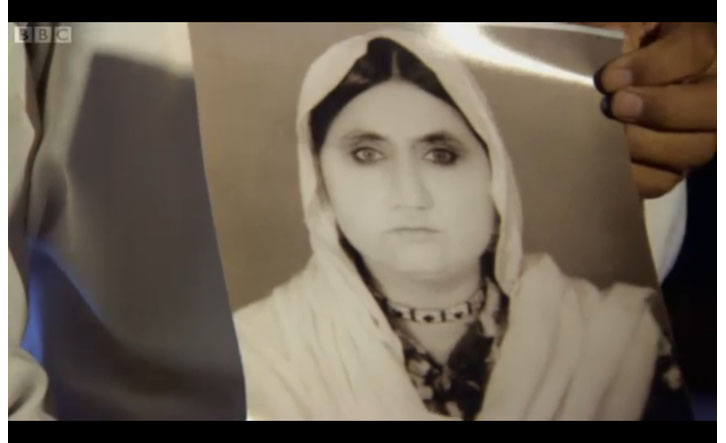

Bibi Mamana, one of the two named women killed by a drone strike. (Image: BBC Panorama)

Among the 550 names of identified people killed in drone strikes in Pakistan, there are people from all walks of Pashtun life. There are farmers and fighters, militant leaders and tribal elders, old men and children.

But one group is almost entirely absent from the list of names: women.

Just two of those who have been identified with their own names are women. This doesn’t mean that only two women have been killed – the available reporting indicates that at least 50 women have died in the nearly 380 drone strikes that have hit in the area. Rather their absence from the list is a reflection of the position of women in Pakistan’s deeply conservative tribal belt, where most people are ethnic Pashtuns (also called Pukhtuns).

Women in Waziristan, the region most affected by drones, live under strict purdah – the practice of keeping themselves separate from men to protect their honour. This means that they are veiled when in public, do not speak to men aside from close relatives, and have separate quarters in homes to remain out of sight of male visitors.

Anthropologist Dr Amineh Hoti – who is Pashtun herself – has written about how wealthier women will often leave the house only in the curtained-off back seat of a car, driven by an elderly retainer.

Uncounted

Women are estimated to represent fewer than 2% of the minimum 2,500 people killed in drone strikes, which could suggest that the woman’s status provides a certain level of protection. But it could also mean that they are not being counted.

The practice of purdah extends beyond women’s physical bodies. ‘This is a purdah system and women are at the core of “sharam”, or honour. Therefore exposing any details about them in public – including their names – is not considered respectable or decent as seen by Pashtuns,’ explains Hoti.

‘There’s this taboo that even educated men think that you should not talk about your female relatives; you should not name them,’ agrees Emal Pasarly, a reporter for BBC Pashto, who has covered Waziristan extensively.

Asking a Pashtun man for the names of his wife and sisters is therefore considered offensive – even if it’s to discover whether they are dead.

The sensitivities around discussing women in a household are so pronounced that academics have raised concerns that their deaths may be under-reported.

‘Strict segregation can mean that neighbours or extended family members may not know how many women and children were killed or injured in a strike,’ wrote researchers from Stanford Law School and New York University School of Law in their joint report, Living Under Drones.

‘It’s difficult unless you’re a relative or unless another woman knows who’s inside the house,’ adds Pasarly.

It is notable that one of the women identified by name was a Spanish woman whose death was reported by the Spanish press. Raquel Burgos García, who died in a strike on December 1 2005, had moved to Waziristan with her husband Amer Azizi, who was suspected of involvement in the September 11 and Madrid attacks.

Named

The other adult woman, Bibi Mamana, was a grandmother. Conditions for older women are more permissive because they are past childbearing age, explains Pasarly. Photos of Mamana appeared in the press after her death and her family gave media interviews about her death.

The strict purdah that dominates women’s lives in Waziristan is a recent phenomenon rather than an integral part of Pashtun culture, Pasarly points out.

He recalls seeing women working in the fields in neighbouring provinces of Afghanistan as recently as 1999 – wearing shawls but no burqas – as well as meeting and interviewing women. Both would be unthinkable now. The change in attitudes is due to the rise in extremism and Taliban beliefs, he says. ‘They are confined to their homes.’

And even in death, their identities are hidden from the world.