During his campaign for President, Donald Trump promised to “bomb the shit” out of the Islamic State, and target the families of accused terrorists – an outright violation of international law. He advocated that the US begin waterboarding detainees once more, and suggested other forms of torture be employed.

This month, after a single short meeting with retired US Marine Corps General James Mattis, Trump said he may rethink his position on waterboarding – convinced by the man he has nominated for Defense Secretary that “beer and cigarettes” may be just as effective as what American officials have termed “enhanced interrogation techniques.”

Trump’s erratic behavior has left advocates for civilians in conflict struggling to guess what White House policies they should steel themselves for over the next four years. One question in particular lingers: how will Trump approach an executive order issued this July by President Obama, which appears to be having a noticeable influence on the US approach to non-combatant deaths.

Executive order 13732 lays out the US approach to civilian casualties across multiple conflict zones including Iraq and Syria, as well as in countries like Pakistan and Yemen where the US carries out covert drone strikes.

Obama instructed “all relevant agencies” to take precautions to reduce the likelihood of civilian casualties, and to conduct assessments “that assist in the reduction of civilian casualties by identifying risks to civilians and evaluating efforts to reduce risks to civilians.” The July 1st order includes a wide range of best practice ranging from the training of Pentagon and CIA staff, to developing and acquiring greater intelligence in the field with an eye to protecting non-combatants.

The order also instructs government agencies investigating civilian casualty incidents to incorporate “credible information from all sources” including NGOs – as well as to share best practice with foreign partners, and to work with the Red Cross to “assist in efforts to distinguish between military objectives and civilians.” Government agencies are also required where relevant to acknowledge responsibility and offer condolence payments to victims or their families, in the event that civilians are killed or injured.

Bombs are loaded aboard the aircraft carrier USS Dwight D. Eisenhower in October 2016. With more than 50,000 US munitions so far dropped on Iraq and Syria, civilian casualties are inevitable (U.S. Navy/ Petty Officer 3rd Class Andrew J. Sneeringer)

Big signal

In some respects, the order solidifies steps that the military had begun to adopt after mounting civilian deaths in 21st century conflict zones – particularly Afghanistan, where reviews led to new directives seeking to limit civilian casualties from certain military maneuvers. For those who had pressured the Bush and Obama administrations for years to reform their civilian casualty rules and offer greater transparency, the recent executive order has been significant.

“To me it’s a pretty big signal to the rest of the world that the US takes seriously civilian harm that it causes and tries to minimize that harm as much as possible,” said Sarah Holewinski, former director of the Center for Civilians in Conflict and a State Department official until last year. “Taking away the executive order would be just [the same] as creating it – it would send a message.”

The Trump transition team did not answer multiple requests from Airwars to clarify how it may approach the executive order or civilian casualties more broadly. The President-elect’s appointed national security adviser, retired Gen. Michael Flynn, also did not respond to requests for comment. Michael Ledeen, who recently co-authored a book with Flynn on how to win “the global war against radical Islam,” said in an email to Airwars that civilian casualty policy was “way outside” of his own expertise.

Flynn – whose disparaging remarks about Muslims, reported attempts to blame Iran for the Benghazi attacks while head of the Defense Intelligence Agency, and conspiracy theories shared on social media have raised substantial concerns – has in the past described the US’s widespread use of drone targeted killing as wrongheaded.

“We’ve tended to say, drop another bomb via a drone and put out a headline that ‘we killed Abu Bag of Doughnuts’ and it makes us all feel good for 24 hours,” Flynn told the Intercept in an interview last year. “And you know what? It doesn’t matter. It just made them a martyr, it just created a new reason to fight us even harder.”

Laura Pitter, senior national security counsel at Human Rights Watch, says there is hope that both Mattis and even Flynn – and the military establishment at large – could serve as checks on Trump’s more volatile impulses.

“Once he [Trump] is in a position where he is actually involved in carrying out some of the policies that he’s talked about, he’s going to get contrary advice to what he’s been saying on the campaign trail,” Pitter said in an interview with Airwars. To do away with the executive order, she added, “would be very unwise.”

Wreckage of vehicles destroyed in an airstrike on Raqqa, Syria on April 1st 2016 which the US now admits killed at least three civilians (Picture courtesy of Raqqa is Being Slaughtered Silently)

‘Humane aspect’

Earlier this year, Airwars director Chris Woods met with top officials at US Central Command in Tampa, who insisted that civilian harm mitigation is central to the strategy of the anti-ISIL Coalition currently bombing both Iraq and Syria.

“It wouldn’t make operational sense to just go into this bombing left and right you know – wiping out ISIL at the expense of the civilian population,” said a senior CENTCOM official. “So there’s a humane aspect to it but also an operational aspect to it.”

Those remarks are published in Limited Accountability, a wide-ranging Airwars audit of the US-led Coalition’s air campaign against ISIL. Among other findings, official estimates of civilian deaths per airstrike in Iraq and Syria are found to be far lower than for other recent US campaigns, including secretive drone strikes in Pakistan, Yemen and Somalia.

In Afghanistan, where the UN has tracked civilian deaths from international airstrikes since 2009, one civilian died on average every 10 to 14 airstrikes between 2010 and 2014. As the audit notes, “Similar civilian fatality ratios if applied to Iraq and Syria – a hot war involving thousands of Coalition airstrikes on urban centres – would lead to expectations of 1,500 deaths or more in the first two years of strikes. This is precisely what the public record indicates.”

Instead, the Coalition has acknowledged only 173 civilian deaths since the start of its air campaign over two years ago – all admitted to by the United States.

Yet there are signs that the recent Obama executive order is nudging the military towards a greater degree of transparency. More than 120 of those US-admitted deaths in Iraq and Syria were confirmed just in the past five weeks. And starting in December, CENTCOM handed over publication duties to the Coalition, which will now release monthly updates on reported allegations – assuming the new administration doesn’t step in the way.

Though CENTCOM has turned over responsibility for investigations to the Coalition (whose main staff are principally American), there are few signs that other members of the Coalition are intent on divulging the results of their own civilian casualty investigations. To date, non have admitted civilian victims resulting from their strikes. As the December 12th Airwars audit notes, “it is unacceptable that major democracies such as Belgium, the Netherlands, Australia and Denmark have chosen to wage semi-secret conventional wars – with affected civilians on the ground, citizens at home and monitoring agencies unable to hold these governments to account.”

During the audit – at the request of CENTCOM officials – Airwars provided detailed information on 438 publicly alleged civilian casualties tracked to that point. As the now-published report details, “a number of new incidents of potential concern were flagged [by CENTCOM] which were then sent out for assessment and possible investigation.”

These steps, halting as they are, encourage advocates. But could they withstand a President who seems capable of undoing eight years of careful Presidential policy-making with a phone call and a few tweets?

Therein lies the fragility of an executive order – an order which a successor President can reverse at will.

“The DoD has done a lot of good things, but it is our view that these are not yet enshrined in policy to the point where 20 years from now when current soldiers and officers are gone, these things will be remembered,” said Marla Keenan, Director of Programs at the Center for Civilians in Conflict.

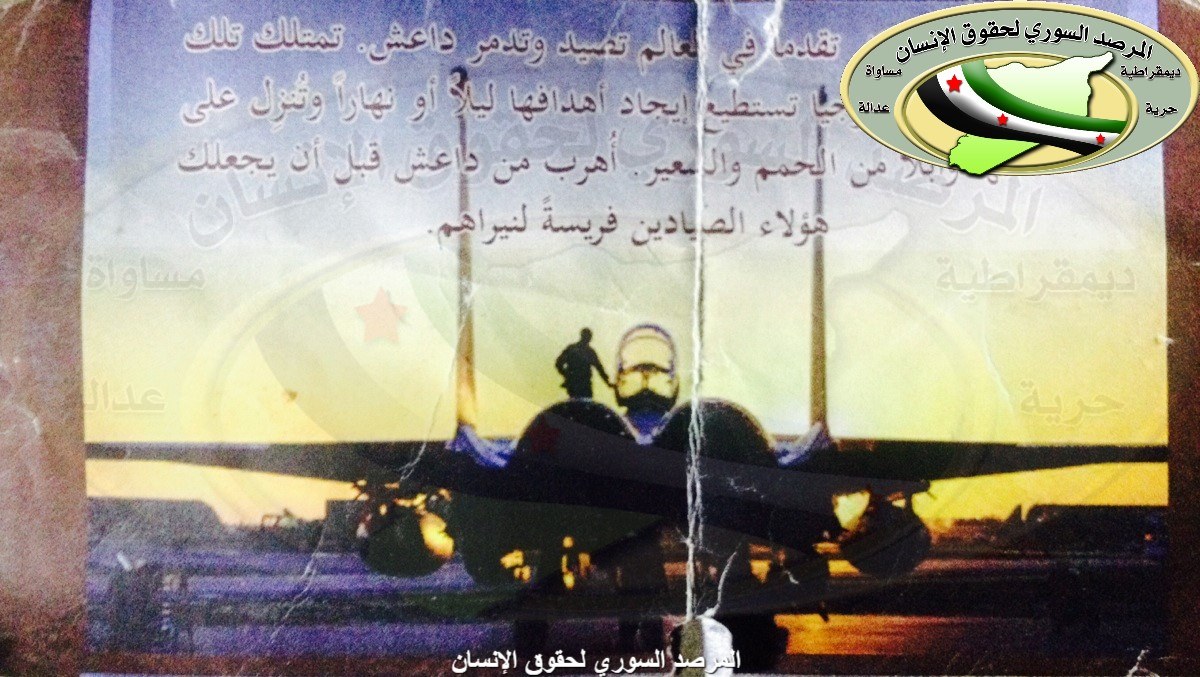

Coalition leaflets dropped on the town of al Mayadeen in Syria on September 9th 2016 warned civilians of impending airstrikes (via Syrian Observatory for Human Rights)

‘Hard to ignore’

After the release of the latest batch of civilian casualty investigations on December 1st, Airwars spoke with Colonel John J. Thomas, the chief spokesperson for CENTCOM. Thomas, who served in both Iraq and Afghanistan, said that particularly during his deployment to Kabul in 2007, officials began to see “that civilian casualties threaten an entire coalition.”

Echoing Keenan, Thomas said that in an organization as large as the US military, where soldiers rotate and officials come and go at the Pentagon, “priorities shift and people get busy with things.” Without the executive order, focus and institutional memory could wane.

“When it’s clearly put in front of you, that this is one of the things you must take the time to look at, it makes a difference,” the colonel noted.

“What the executive order does is it gives us permission in a sense to dedicate the resources,” Thomas added. “What this has given us the opportunity to do is look backwards and understand what has happened in these specific instances and also gives us a better chance of learning from them.”

“When someone like Airwars brings us info that we weren’t even aware of… we check it out against our strike list,” he said.

“It’s good to have the priorities clear,” he added, comparing the order to Freedom of Information Laws. “It’s hard to ignore an executive order on a specific issue.”

Airwars director Chris Woods, who authored the transparency audit released on December 12th, said that Obama’s executive order had a demonstrable effect over the course of the study.

“Back in May we assessed CENTCOM’s casualty monitoring process as pretty much unfit for purpose. Sixty per cent of claims weren’t being looked at, and most that were were dismissed out of hand within a day or so. More recently we’ve seen the US military reaching out to external monitors like ourselves – and adopting a more systematic approach to casualty counting. The State Department also has a formal civilian casualty monitoring role – and just unveiled a new reporting mechanism for NGOs.”

As President Obama leaves office, he will pass broad military powers to his successor. Civilian casualties will continue to occur, however President Trump approaches the issue. But for advocates on behalf of civilians affected by war, the task of engaging with the incoming administration could be difficult.

“For the human rights community, with Flynn, for Mattis, for Trump and whoever becomes Secretary of State, we have to get back to basics and get smarter about our arguments,” says Sarah Holewinski. “We had 8 years of being invited to meetings at the Obama White House and talking over the particulars of an executive order. When it comes to the Trump administration, we have to hold our arguments in very basic terms, about why causing civilian harm is detrimental to our national security, and why addressing those things are important to American identity.”