Recent change in French narrative suggests its forces may have harmed civilians in the war against ISIS - but officials refuse to say more.

On May 16th 2017, Sajid Ahmed Sajid and his brother Amer Ahmad Sajid, two men in their fifties and each with a salt and pepper beard, were killed by a bomb that struck their house in the well-to-do neighbourhood of Al-Najjar in West Mosul, according to locals and local media.

The Coalition’s public account of the attack differs, insisting that “during a coalition strike against an ISIS commander, ISIS headquarters and VBIED operation which destroyed the VBIED operation, two civilians were unintentionally killed when they inadvertently walked into the blast radius of the strike.”

Yet which of the Coalition allies active during Mosul was responsible for those deaths – the US, the UK, France, Australia or Belgium – remains unclear.

Between May 8th – 23rd 2017 according to official records, while the battle for Mosul was raging seven international Coalition airstrikes on parts of the city controlled by ISIS, as well as an airstrike in Tabqa, Syria, between them killed at least six civilians and wounded one. While the Coalition has made public that tally, it has not specified which military within the international alliance was responsible for each event. According to an agreement between the allies, it falls to each individual Coalition member to announce its own responsibility for what militaries call ‘collateral damage’.

In that same time period and geographic area, the French military reported 24 strikes “carried out by French aircraft in Iraq and Syria”. It is impossible to know whether France is responsible for the deaths of the Sajid brothers – or indeed of any other civilians killed in the course of these seven strikes – because the French army doesn’t disclose the day or the precise location of its actions.

Asked in early December 2018 about potential French involvement, the spokesman for the French Military Chiefs of Staff, Colonel Patrick Steiger, didn’t answer directly and referred this reporter instead to the Coalition. “We don’t want to single ourselves out. The answer lies at the Coalition level,” he said. Yet, in March 2017 Colonel Steiger had previously said that based on “the current state of our information, we have no knowledge of collateral damage. But absolute certainty doesn’t exist.”

This subtle communication shift suggests that French air or artillery strikes may have killed civilians, whether in May 2017 or at another time. Yet the French Minister of the Army, Florence Parly, has refused to comment on the issue.

Intense campaign

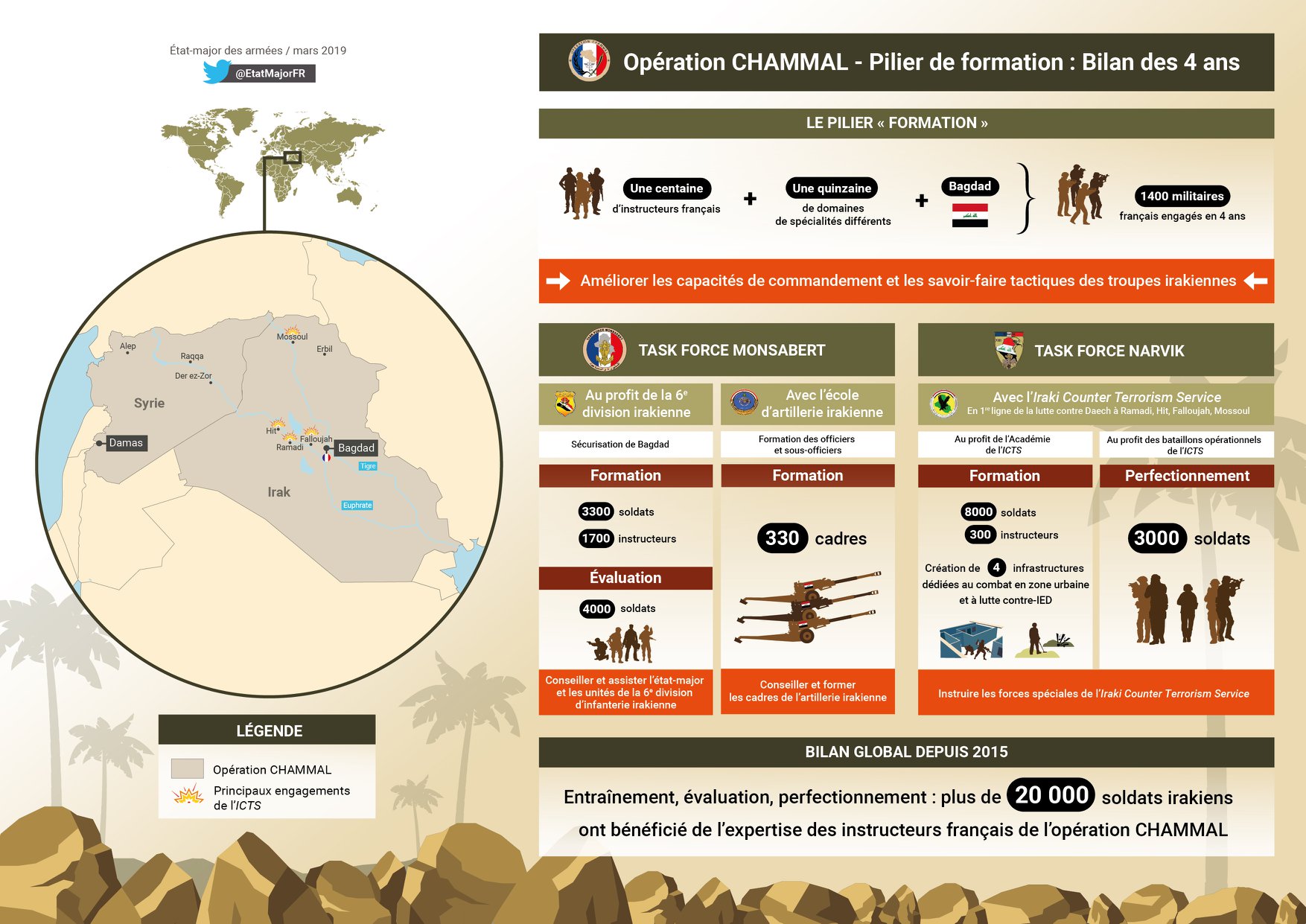

Starting in September 2014, the French army has been participating with ten of its Rafale aircraft and artillery batteries alongside 15 other countries in the US-led Operation Inherent Resolve (OIR), to help defeat ISIS in Iraq and Syria.

Between August 2014 and April 20th 2019, the Coalition launched 34,334 air and artillery strikes, which were conducted by the US to a significant degree. “During this period, based on information available, CJTF-OIR assesses at least 1,291 civilians have been unintentionally killed by Coalition strikes,” the Coalition presently believes. Some 122 allegation reports are still under assessment.

This figure is significantly lower than the one published by Airwars, which presently estimates that between 7,743 and 12,561 civilians have been killed, based on confirmed or fair reports. The Coalition’s tally also appears low compared to previous conflict figures. According to UN estimates, in Afghanistan between 2010 and 2014, an average of one civilian was killed for every 14 international forces airstrikes. Although rules of engagement differed, these airstrikes targeted for the most part rural areas with far fewer inhabitants than Iraqi or Syrian large cities.

The US, which has conducted the majority of all Coalition airstrikes, is also statistically likely to be responsible for the majority of civilian harm in Iraq and Syria. Until April 2017, all civilian losses admitted by the Coalition (which by then amounted to 229 deaths), were caused by the US Air Force, officials confirmed at the time. Frustrated at being the only country to concede civilian casualties, the Americans stopped releasing information specifying countries’ actions, and have only published global figures at Coalition level since.

Eventually, the UK admitted in May 2018 to the death of one civilian (in the course of more than 1,800 strikes) and the Netherlands has conceded three civilian casualty events – though refuses to say how many non combatants were killed or injured. Australia admitted on February 1st that “between six and 18 civilians may have been killed” during a raid it was involved in at Mosul in 2017, and had previously conceded two additional events. France is thus the only active Coalition member not to concede any civilian harm publicly.

France was second only to the United States in its military contribution to the war against ISIS – but has not declared any civilian harm from its actions.

1,500 French strikes

After the US and the UK, France has launched the greatest number of Coalition airstrikes (it ranks second if French artillery figures are also included) – that is to say, 1,500 strikes since the beginning of the operation.

“Many strikes took place in heavily populated urban areas where significant civilian harm has been credibly reported,” Chris Woods, Airwars director, said. For instance, French aircraft launched 600 airstrikes during the battle of Mosul. In this urban environment, where civilians were used as human shields by ISIS and were sheltering in unknown locations, and where blasts rebound easily, risk of civilian harm ran high. “It’s inconceivable that France hasn’t been responsible for civilian harm in such an intense conflict,” Chris Woods said.

“When you conduct combat in an urban area, you kill civilians. You can take steps to minimize deaths, but you have to be honest about the risk,” a former high-level US defense official said when interviewed for this article.

Despite what others see as the inevitability of civilian harm from urban strikes, the French military works on the assumption that since its rules of engagement (which it refuses to reveal) are very restrictive – and that since it takes great precautions, that it is unlikely to have harmed civilians.

For example, if a civilian is standing in proximity to a target area, the French military claims that it would cancel a strike. “In summer 2017, we stopped airstrikes in the Mosul area because we couldn’t guarantee the precision and the effect of strikes,” the French military Chief of Staff spokesman said. However, due to limited information, it remains difficult to demonstrate that French rules of engagement are safer than those of other allies.

Experts say that it’s not a lack of precision that kills civilians, as weapons currently used are very precise. According to several military sources, the bombs used by Coalition members – including France – in airstrikes in Iraq and Syria, such as GDAM, AASM, or GBU, are all laser- or GPS-guided. The main issue comes from incorrect or outdated intelligence, or from not seeing civilians in the targeted area. “Precision munitions bring little benefit to trapped civilian populations in urban centres,” Chris Woods said.

The French military say that 90% of the airstrikes it has launched in Iraq and Syria have been close air support strikes (CAS), while only 10% have been planned strikes. These CAS strikes are called in and guided by allied fighters on the ground during their progression, when they need an enemy position to be destroyed.

Planned strikes are instead aimed at pre-identified targets such as operational centres or weapons factories. Militaries often have days to watch a target and identify potential patterns of civilian movement surrounding them. According to the French rationale, CAS are less risky because there is an officer on the ground who can directly see the target.

Yet experts disagree, arguing that the target is not necessarily in sight and that indications for a strike might lack precision. “Vision depends on the ground. But in close air support of troops in contact, you are not able to spend a long time observing the target and it’s difficult to minimize civilian harm,” the former high-level US defense official said.

In February 2019, and for the first time, a senior French military official publicly admitted “an excessive cost” and “significant destruction” resulting from the Coalition’s tactics against ISIS. Colonel Francois-Regis Legrier, who had been in charge of directing French artillery supporting Kurdish-led fighters in Syria since October 2018, wrote an article in the National Defence Review at the end of his mission.

“By refusing ground engagement, we unnecessarily prolonged the conflict and thus contributed to increasing the number of casualties in the population, We have massively destroyed the infrastructure and given the population a disgusting image of what may be a Western-style liberation leaving behind the seeds of an imminent resurgence of a new adversary,” Colonel Legrier wrote.

Legrier’s article was abruptly removed, and the French Minister for the Army has sought to sanction him.

French artillery crews in action against ISIS – part of Task Force Wagram (Image via Armee francaise)

A lack of accountability

Killing civilians is not necessarily considered a crime during conflict according to international law, as long as strict conditions of proportionality and distinction are respected and all feasible precautions to protect civilians are taken.

Yet when civilians have been harmed, States “are under an obligation to conduct prompt, independent and impartial fact- finding inquiries in any case where there is a plausible indication that civilian casualties have been sustained, and to make public the results,” according to the former UN Special Rapporteur on Counter-Terrorism and Human Rights, Ben Emmerson.

Still, NGOs and observers have often criticised the weakness and lack of transparency of the Coalition’s investigations. After a strike, the military conducts a Battle Damage Assessment (BDA), which reviews the impact of the attack, looking mainly at whether the target was reached. It also allows an opportunity to see if civilians were harmed. The BDA is largely based on pilots’ observations immediately after a strike, and a review of battlefield surveillance footage if there is any. It is a “basic” process according to one French defence official. “We can’t see everything. There can be shrapnel and it can wound someone. This, we don’t know about it,” Colonel Steiger said.

Since the beginning of Operation Inherent Resolve, 200 allegations of civilian casualties potentially involving the French military have been investigated, this reporter has learned. Yet French army officials refuse to make the results of those assessments public.

When allegations of civilian casualties are brought up, a Coalition team in Al Oudeid base in Qatar investigates claims by reviewing all footage and images available, along with other materials, for example external media or NGO reports. When the Coalition assesses that a death is “not credible”, it doesn’t mean that it didn’t occur, but that the team was unable to gather sufficient information about the case at that time.

The team is made up of a few analysts, and the Coalition admits that it doesn’t have enough resources to investigate every case. No French officer is part of this team but the French military say that they conduct their own investigations in parallel. These consist of reviewing the same images and other information, along with the insights of a munition expert who assesses the range of the explosion.

Amnesty International has criticised this internal assessment process, which it says does not usually include information gathered at the strike’s location, and from witnesses. The organisation stresses that aerial images have their limits. “You can’t see through roofs and walls, you miss families that don’t leave their hiding places for days. Taking drone footage after an airstrike is not a substitute for a proper investigation,” Brian Castner, Amnesty International’s weapons adviser said.

‘No public pressure’

Just as France’s investigations into alleged civilian harm are not comprehensive and lack transparency, so too with its communication about military operations. In the beginning of the war against ISIS, the French army used to publish daily reports on its actions, specifying the type of aircraft and munitions used, the target, and a fairly precise location. However since March 2015, France has instead released weekly reports that only give the number of missions and broad details of “neutralised targets”, as well as the general location of the attack – usually at province level.

“There is no public pressure to have all the information. We haven’t felt that we needed to say more,” claims French military Chief of Staff spokesman Colonel Patrick Steiger. This approach contrasts with other Coalition members such as the UK, which has continually published detailed reports of its own military operations. In this context, it is extremely hard for external observers to raise the alarm on allegations in which France might be involved.

Within the French political system, Members of Parliament have also failed to provide a watchdog role regarding civilian casualties. “We talked about it two or three times during sessions. But it is not an issue because we have not been notified of any incident that can be problematic,” Gilbert Roger, Seine-Saint-Denis Senator said.

This approach contrasts sharply with the US, where the National Defense Authorization Acts of 2018 and 2019 oblige the Pentagon to answer to Congress annually on civilian harm, for example.

France’s refusal to identify or concede civilian casualties from its actions – while limiting any admissions to the Coalition’s broader tally – has far reaching consequences. The International Committee of the Red Cross highlighted the risk of responsibilities being obscured in a recent report. “This can create a climate in which stakeholders, political and military alike, perceive themselves to be free from the scrutiny of accountability processes, and act beyond the parameters of their usual normative reference frameworks.”

Errors are also likely to happen again unless they are identified. “Military learn from their mistakes by looking at how civilians died. But it becomes less likely if they are acknowledged at the coalition level only,” Chris Woods said. “And with such a complete lack of transparency from the French military, Syrian and Iraqi civilians who have been caught up in French actions will forever be denied accountability and possible compensation.”

This article was originally published in French in Liberation. The English-language version here appears courtesy of Marie Forestier, and of Liberation.