Despite being the most transparent among anti-ISIS Coalition members, non-admission of urban civilian casualties by UK is deemed unrealistic in new parliamentary report.

A major new Airwars report submitted to the British Parliament is challenging UK claims to have harmed no civilians during the battles of Mosul and Raqqa, despite almost 1,000 targets having been struck by the RAF. The UK’s involvement represented one of its biggest military actions since the Korean War in the 1950s.

The 43 page report, Credibility Gap – United Kingdom civilian harm assessments for the battles of Mosul and Raqqa, was submitted by Airwars in response to an inquiry by the UK Parliament’s Defence Select Committee – which has also published a shorter version of the report. As well as taking oral evidence from senior British military commanders, the Committee has received written submissions from the Ministry of Defence and NGOs including Amnesty International, Save the Children and Article 36.

Airwars is blunt in its own submission. While welcoming overall UK transparency, it challenges the MoD’s narrative of an antiseptic airwar in Iraq in Syria: “It is the view of Airwars that the Ministry of Defence’s claim of zero civilian harm from its actions at Mosul and Raqqa represents a statistical impossibility given the intensity of fighting, the extensive use of explosive weapons, and the significant civilian populations known to have been trapped in both cities,” the report notes.

In both battles Airwars has in total identified 413 alleged civilian harm events where British involvement is in theory possible based on public reporting of strikes: 176 of these were in Raqqa and 237 in Mosul. For the majority of these cases the UK’s position is still unestablished. Some 40 events have however been directly referred to the Ministry of Defence for assessment. In 39 of these cases the MoD rejected any involvement, while one case remains open.

Looking at the bigger picture, the Coalition has conceded civilian harm in 36 out of the 413 known alleged events for the battles of Mosul and Raqqa. While the US was responsible for around two thirds of Coalition strikes in Mosul, and an estimated 95 per cent of strikes in Raqqa, as the second most active belligerent, UK involvement in civilian harm events is feasible.

The high number of reported civilian casualties is not the only reason the UK’s claim of zero urban harm is implausible. The battles of Raqqa and Mosul made clear that the benefits of precision weaponry are greatly overstated when it comes to urban warfare. As the report notes: “The greater the intensity of explosive weapons use – predominantly in urban areas – the higher the civilian toll.”

Read our new report, Credibility Gap, in full

During the campaigns, much of the Old City of Mosul and almost 70% of Raqqa’s entirety were destroyed or rendered uninhabitable, according to the United Nations. Much of the damage was caused by Coalition actions with at least 50,000 munitions fired, along with significant destruction that came from ISIS actions and either government forces or proxies. All parties combined reportedly killed at least 9,000 civilians in Mosul and 2,400 or more in Raqqa, according to current best estimates.

For the UK, the 500lb Paveway IV bomb has generally been the weapon of choice, accounting for two out of three weapons released during military operations in Iraq and Syria. The Paveway IV, a wide area effect munition with a large explosion radius, is poorly suited to urban warfare according to Airwars. As the report states, its use “would over the course of hundreds of strikes, have caused potentially significant additional unintended harm to civilians and infrastructure when released on dense urban areas.”

In combination with the intensity of bombardment – the Coalition released an average of 3,200 munitions per month in Mosul between October 2016 and July 2017, for example – there are many other reasons to doubt UK claims that civilians were not harmed by its actions. ISIS deliberately placed civilians in areas where air-dropped munition might harm them. Nonetheless, “a key finding of Airwars is that the Coalition did not significantly modulate its use of explosive weapons once operations focused on Raqqa,” where an average of 4,000 munitions per month was dropped on a much smaller area.

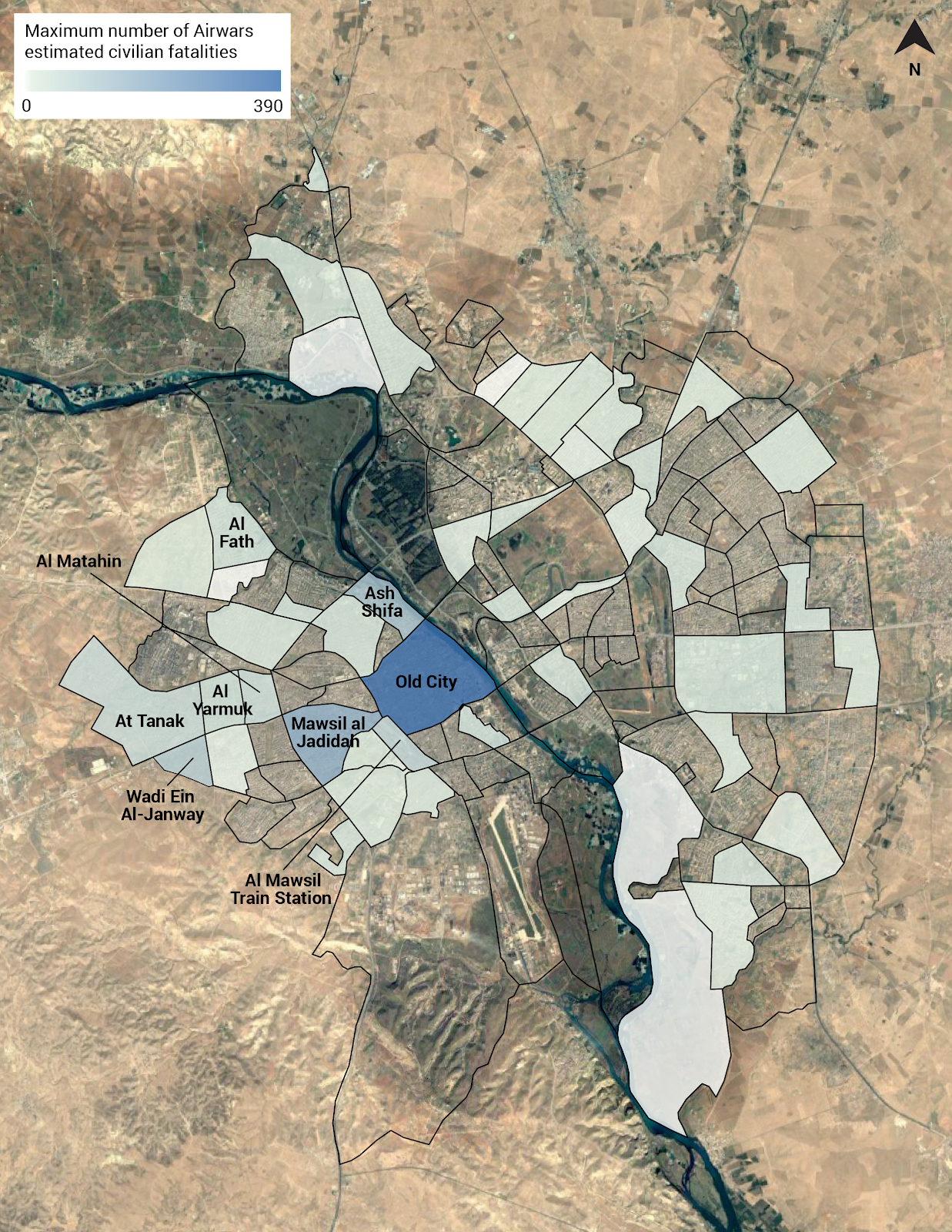

Choropleth of Airwars estimated maximum number of fatalities in Fair and Confirmed graded incidents during the Battle of Mosul (excluding incidents for which coordinates are missing or geo-accuracy is at city- or town-level).

‘A fool’s errand’

British claims to have harmed no civilians during the battles for Mosul and Raqqa stand in direct contrast to the views of the most senior UK commander in the Coalition, who helped devise the strategy to capture both cities from ISIS.

“War is brutal, and if you want to fight in cities, everything is more extreme,” Major General Rupert Jones, who served as deputy commander of the Coalition, told the Defence Select Committee inquiry in May 2018.

“Everything is heightened in a city – the number of troops you need, the amount of munitions you drop, and the amount of suffering… The idea that you can liberate a city like Mosul or Raqqa without – tragically – civilian casualties is a fool’s errand,” concluded Jones.

Despite such statements, and similar ones by other officials, “British defense officials, at least while still serving, have often appeared unable or unwilling to take the logical step of concluding that Britain, as the most active Coalition member after the United States, would have a proportionally significant share of such casualties.” It took the UK 44 months to acknowledge any civilian harm during its mission in Iraq and Syria, raising doubt about its willingness to concede such events.

The Airwars report also puts the process of examining cases and quality of assessment under scrutiny, as the UK mostly relies on the Coalition’s own civilian harm cell. Most commonly, the Coalition relies on what is observable during events, meaning what can be seen from footage taken from above.

This process is problematic, since most civilian harm in urban fighting occurs in unobservable spaces. Families and individuals were killed in significant numbers in both Mosul and Raqqa when buildings collapsed on top of them – an outcome which military surveillance rarely captures. Airwars also found that a significant proportion of UK strikes targeted buildings. According to MoD reports released at the time, during the Battle for Raqqa 63% of UK strikes targeted buildings, while 31% of strikes hit such structures during the Battle for East Mosul.

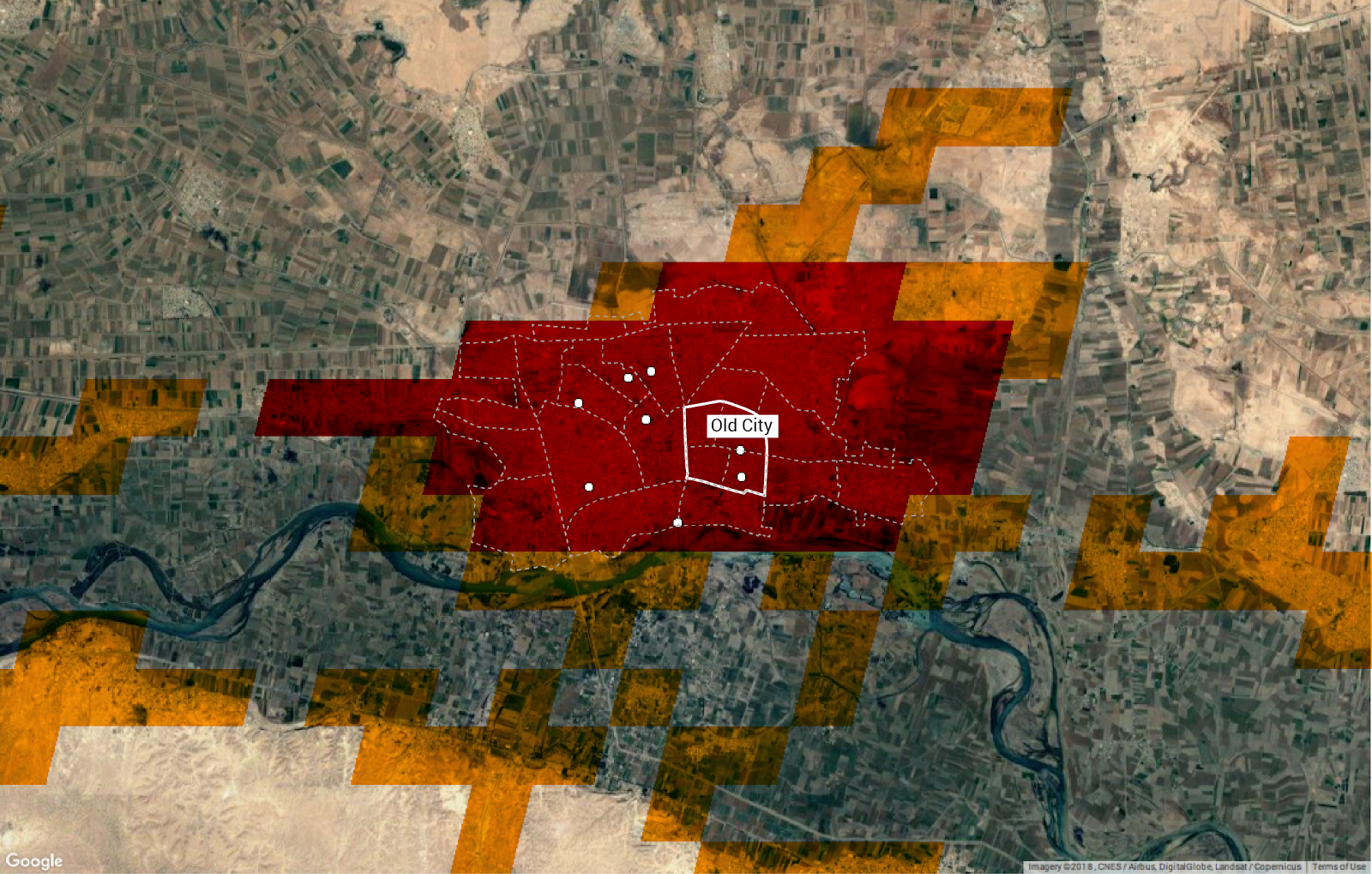

Map showing how Credible civilian harm incidents in the Battle of Raqqa (for which Airwars has received Military Grid Reference Coordinates to an accuracy of 1 m or 100 m) are located in High Density Urban areas.

Recommendations for improvement

As a result of concerns about the implausibility of UK claims of no civilian harm during the battles of Mosul and Raqqa – and the MoD’s internal review process – Airwars makes several key recommendations to help improve British monitoring and reporting of civilian harm:

As the Airwars report notes, despite significant improvements in overall civilian harm assessment – especially at a Coalition level – there is still much room for improvement by the UK in how it deals with the consequences of its military actions.

As the Airwars report concludes, “for affected local civilians in Iraq and Syria, accountability is the issue.” After many years of war, belligerents taking proper responsibility for their actions could offer some relief for Iraqi and Syrian families. Without such accountability, there is a risk that these communities might once again believe themselves abandoned – and become a future target for extremism.