Declassified Pentagon files reveal systemic failures in target identification that led to civilian deaths, from mistaking children for weapons to faulty surveillance

On May 3rd, 2023, the US military announced that it had targeted a ‘senior Al-Qaeda leader’ in a strike in Syria. That same day, the White Helmets shared images from the scene where they were the first responders to the strike. They reported that a civilian had died: Lutfi Hassan Masto, a 60-year old farmer killed alongside his sheep.

More than a month later, CNN revealed that the US military had decided to open an inquiry into the incident – known as an ‘AR15-6’ – after doubts grew about the identity of the victim. A US official admitted “we are no longer confident we killed a senior AQ official.”

AR15-6s are the US military’s most detailed review of civilian harm allegations. The same procedure was initiated after a strike killed ten civilians in Kabul, Afghanistan on August 29th, 2021, when the US incorrectly identified aid worker Zemari Ahmedi as an Islamic State militant.

Earlier this year The New York Times published 66 partially redacted pages of that AR15-6, declassified by the Pentagon after a successful Freedom of Information Act request.

This is the latest document released by the NYT, adding to more than a thousand civilian harm assessments released relating to the US-led Coalition campaign in Iraq and Syria during the war against ISIS. While most of these assessments were shorter-form investigations intended to be more adaptable to high tempo situations, more than a dozen were full AR15-6s – each one dozens of pages long.

Over the past year, Airwars researchers have been coding and reviewing this tranche of declassified civilian harm assessments. With new funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, we are now working in partnership with researchers at the Universities of Auckland, Minnesota, Newcastle and Ottawa to produce a comprehensive set of resources analysing this material due to be published over the next year.

In advance of that analysis, we are releasing a selection of excerpts of civilian harm cases chosen by our researchers, which place the decisions made in the Kabul strike in the context of a pattern of decision-making, and which can also inform understandings of the May 3rd strike on Lutfi Masto.

“An unknown heavy object”

Concerns with the quality of the surveillance feed have been observed by Airwars researchers throughout our analysis of the declassified Pentagon documents as having contributed to civilian harm incidents.

In the case of the Kabul strike, officials note in the AR15-6 that the surveillance feed “obscured the [ID] of civilians” and that the “trees and courtyard overhang limited visibility angles”.

In other cases, reviews of higher quality imaging prompted only by civilian harm allegations have also revealed that weapons originally perceived to be held by ISIS militants were in fact never there to begin with.

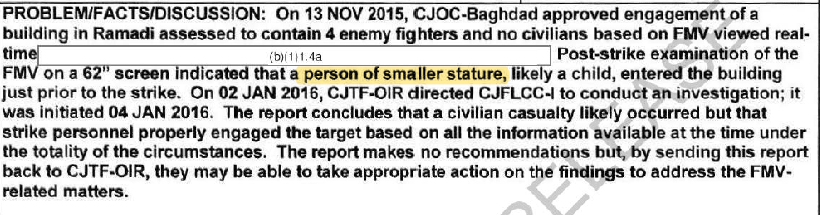

On November 12, 2015, one civilian – a child – was unintentionally killed in Ramadi, Iraq, after initially being perceived as “an unknown heavy object” during targeting.

The report admitted that when the video footage was reviewed on a 62” high definition TV, it was clear that the “person dragging a heavy object, was actually moving with a person of possible smaller stature”.

In the incident below, at least seven civilians were killed in Raqqa, Syria, on December 7th 2016 after Coalition forces incorrectly assessed the individuals were carrying weapons and wearing tactical vests. The civilian harm assessment revealed that this was despite the fact that the Coalition observed the building for six hours before it was struck.

“Driving at a high rate of speed”

Understanding how targets are selected is a common challenge for third parties reviewing the consequences of military actions. In both the AR15-6 and throughout many of the documents covering the US-led campaign in Iraq and Syria against ISIS, behavioural patterns were referred to as justifications for target selection: in many harm incidents, the analysis of these patterns has proven deadly for civilians.

On May 11th 2017, declassified documents reveal that the speed at which a vehicle was driving was the reason for the strike. CENTCOM admitted to killing two civilians in the incident in August 2017. The declassified document, released more than three years later, shows that those killed were quickly identified as children by officials reviewing the post-strike observation footage.

The Kabul strike against Ahmadi’s vehicle similarly used the observation of driving habits and techniques to ascertain militant status, even though the reasoning for certain actions during driving could also be explained by a wide range of unobserved factors. In Ahmadi’s case, these factors included the need to visit different areas of his city in order to carry out errands.

During an interview conducted as part of the AR15-6, an official stated that the way that the driver also “carefully” and “gingerly” loaded up the car were all factors in the decision to strike. The New York Times later revealed that those actions were typical of Ahmadi’s usual day at work, where he collected water to assist in humanitarian aid distribution.

“Unexpected collateral damage”

In Kabul, the AR15-6 notes a service member saying that “the explosions were massive” after the strike. Originally thought to be corroborating evidence for the supposed munitions held in the vehicle, military officials later noted that it is more likely that the secondary explosion was caused by a propane or gas tank.

From a strike that killed at least 70 civilians in Hawija that prompted a major investigation and policy reforms in the Netherlands, to a series of strikes on fuel trucks in Iraq that barely made headlines – secondary explosions appear throughout civilian harm assessments as a likely cause of death and injury.

In 2016, the US-led Coalition fired aerial rockets as warning shots over the civilian drivers of fuel trucks in Syria. However, the civilian casualty assessments reveal that these warning shots were rarely effective: some of the drivers simply swerved sharply to avoid the rocket fire or, in other cases, they left their vehicles, waited and then returned after a short time, presumably thinking that the immediate danger had passed.

The significant secondary explosions resulting from strikes on fuel trucks in many of these cases led to the deaths of the civilian drivers.

Other cases of secondary explosions occurred in more densely populated battlegrounds. On January 21st 2017, at least 15 civilians were killed when a strike caused “unexpected collateral damage” in a densely populated neighbourhood in Mosul, Iraq.

Four children were reported killed in the strike. An excerpt from an interview with one of the survivors, conducted by The LA Times, is included in the declassified assessment: “Why would they make a mistake like this? They have all the technology. This is not a small mistake”.

The assessment report is brief, reflective of the shorter form civilian harm assessments conducted throughout the war against ISIS. It does not recommend any further action, such as the opening of the more in depth AR15-6.

In total, Airwars has tracked at least 8,198 civilian deaths resulting from the actions of the US-led Coalition. The US-led Coalition has admitted to 1,437 casualties, with many of those incidents originating as Airwars referrals rather than proactive reviews by the United States military. To date, there remain 37 open cases of civilian harm allegations yet to be resolved.

The excerpts above and the forthcoming analysis reveal much about how the US military navigates the information environment: how it reads militant status within the behaviours of civilians, how secondary explosions are seen as unfortunate but unpredictable – even in the most densely populated areas – and how blurred surveillance footage can lead to children being mistaken for objects.

The US has begun a process of ostensibly reviewing these assumptions, with its new Civilian Harm Mitigation and Response Action Plan underway. Separately the Dutch Ministry of Defense has taken the unprecedented step of releasing a database of all weapon deployments by Dutch F-16s during their involvement in the Coalition campaign in Iraq and Syria. Other members of the Coalition have been less forthcoming. Later this year, Airwars is taking the UK Ministry of Defence to a tribunal to push for the release of their own civilian harm assessment in the single incident in which they admitted to having killed a civilian in eight years of intense campaign.

In the absence of full transparency and accountability for the civilians killed by the US-led Coalition, lessons cannot be appropriately learned for future operations. This failure to reckon with these past actions will continue to have devastating outcomes for civilians, as it has done for the victims of the Kabul strike in 2021, and likely too for Lutfi Masto and his family in Syria last month.

On June 29th, Airwars joined 20 other civilian protection and human rights organizations in calling on the US military to carry out an investigation into the incident in Syria that is robust, transparent, and accountable, with the hopes that this investigation will set a precedent for all future civilian harm allegations.

Authors: Anna Bailey-Morley, Stephen Pine, Alice Smith, and Anna Zahn

Volunteers who are supporting this project include: Anna Bailey-Morley, Stephen Pine, Alice Smith, Nasim Hassani, Arturo Gutierrez de Velasco, Reine Radwan, Nitish Vaidyanathan, and Austin Graff