On the night of October 26, 2019 the US military carried out an operation against ISIS leader Abu Bakr Al Baghdadi in Syria. Local journalists reported the deaths of at least five civilians in the raid. Alongside Baghdadi’s family members and ISIS operatives within the compound, three civilians were reported harmed while passing by the Baghdadi residence at the time.

Following a freedom of information lawsuit by NPR, the US military released the partially redacted 14-page civilian harm assessment it conducted into the incident. The document highlights fresh concerns about both the pattern of US targeting which has consistently resulted in the death and injury of civilians, and the approach to assessing and responding to civilian harm claims.

Both NPR and Syrian website Shbabbek.com identified three civilians likely harmed during the raid by name: Khaled Mustafa Qurmo and Khaled Abdel Majid Qurmo were killed, and Barakat Ahmad Barakat was severely injured. NPR also interviewed Barakat and verified his testimony.

Yet US President Donald Trump called the raid “impeccable” at the time, and to date all claims of civilian harm have been denied by the US Department of Defense (DoD).

Joanna Naples-Mitchell, the lawyer representing survivor Barakat Ahmad Barakat, told NPR that she wants the DoD to take a fresh look at the case, and that “the military has not even taken basic steps to check their own assumptions.”

This research brief presents an annotated analysis of the declassified US military civilian harm review. It appears to show that a near impossible standard for casualty assessment was used in this case; a standard at odds with DoD’s usual, albeit inconsistent, approach to civilian harm reviews.

Read the declassified document in full with select annotations on DocumentCloud here.

A new standard? Image and video metadata from local reporting

On page 9 of the declassified civilian casualty assessment report (referred to as CCARs), the US military analyst questions the veracity of publicly available information, noting that there was no ‘image or video-derived metadata’. The lack of metadata is referenced a further three times in the document.

This appears to be the first time that metadata has been required as part of an assessment into civilian casualties.

Airwars has reviewed 160 civilian harm assessments declassified by the Pentagon regarding their campaign against ISIS in Syria and Iraq, and is in the process of coding and analysing more than one thousand documents in a major new project due to be launched next year. In the documents reviewed to date by Airwars researchers, there has been no mention of metadata having been needed by analysts in order for them to reach a credibility determination.

Though the documents are challenging to process using any computer-assisted software due to frequent redactions and poor quality scans, an initial review using OCR (optical character recognition), also finds no mention of original metadata in any of the more than one thousand declassified documents.

Throughout the campaign, CENTCOM further requested information from Airwars regarding our documentation of civilian casualties in what appeared to become a routine part of their own assessment process, with a quarter of assessments later deemed ‘credible’ originating as Airwars referrals.

Often the information requests were for additional details from our own reporting on the location or dates of civilian harm allegations. A review of information requests from 2017-2020 also finds no evidence of CENTCOM ever having asked for metadata on these cases, including in correspondence dating after the Baghdadi incident.

“Inconsistency, lack of detail, circular reporting”

Under the heading “inconsistency, lack of detail, circular reporting,” the military analyst noted that Airwars assessment criteria does not fit with the assessment criteria for any Combatant Command. This is a key justification for the eventual non-credible determination.

Airwars has long called for transparency and clarity on the assessment criteria used by Combatant Commands, which is itself currently undergoing a major internal reform process within DoD.

In August 2022, the DoD released a civilian harm mitigation and response plan to revise its processes for managing, responding to and learning from incidents of civilian harm caused by its own actions on the battlefield. This document notes that civilian harm assessments and investigations have been “applied inconsistently across DoD, and more resources should be devoted to collecting and analyzing information consistently in these reviews.”

This is not the first time a high level DoD document has admitted to inconsistencies in its own processes. In the executive summary of a major internal review into a mass casualty incident in Syria in March 2019, where dozens of civilians were alleged to have been killed by US strikes, the four star General leading the investigation noted that “the administrative deficiencies contributed to the impression that the DoD was not treating this CIVCAS [civilian casualty] incident seriously, was not being transparent, and was not following its own protocols and procedures regarding CIVCAS incidents.”

One of the few public statements on the criteria by which the US military states that it judges civilian harm allegations is the “more likely than not” standard, as outlined, for example, in DoD’s latest report to Congress.

In a study sponsored by the DoD in 2021, assessing its own civilian casualty policies, this standard was revealed to be inconsistently applied. The report, authored by the RAND Corporation, found that “the standard for deeming a civilian casualty report to be credible often required having positive proof indicating civilian harm in military information, a higher standard than the military’s stated “more likely than not” standard”.

In the case of the Baghdadi incident, the analyst reviewing the harm allegations noted that the claims were “plausible, but not credible”. It is unclear how the analyst determined the difference between plausibility and likelihood in the assessment.

The term ‘plausible’ has been used before in military assessments, though with different results. For example, an incident in which six members of one family were reported killed when a Coalition drone hit a vehicle in Iraq in May 2015 was deemed credible by the US military in its now declassified review. No detailed investigation was conducted or additional information collected due to the time between the assessment and the original reporting. The analyst however noted that it was “plausible” that the six individuals, who had previously been ‘positively identified’ as members of ISIS, were indeed civilians, due to the “descript nature of the CIVCAS allegation”.

Analyst comment on casualty count ranges out of step with own reporting requirements

The analyst comment on page 12 appears to reference ranges of casualty estimates in local reporting as a contributing factor in the non-credible determination.

The use of ranges however is common practice in casualty recording, and is even now explicitly acknowledged as part of DoD’s mandated reporting requirements to Congress, as per the National Defense Authorization Act FY2023, in Section 1057(b), 2C: civilian harm is to be “formulated as a range, if necessary, and including, to the extent practicable, information regarding the number of men, women, and children involved.”

Airwars’ methodology has always included civilian casualty ranges, and is also in line with recommended best practice for casualty recording outlined by Every Casualty Counts in their 2016 Standards for Casualty Recording handbook.

Repetition of known flawed interpretations of ‘hostile intent’

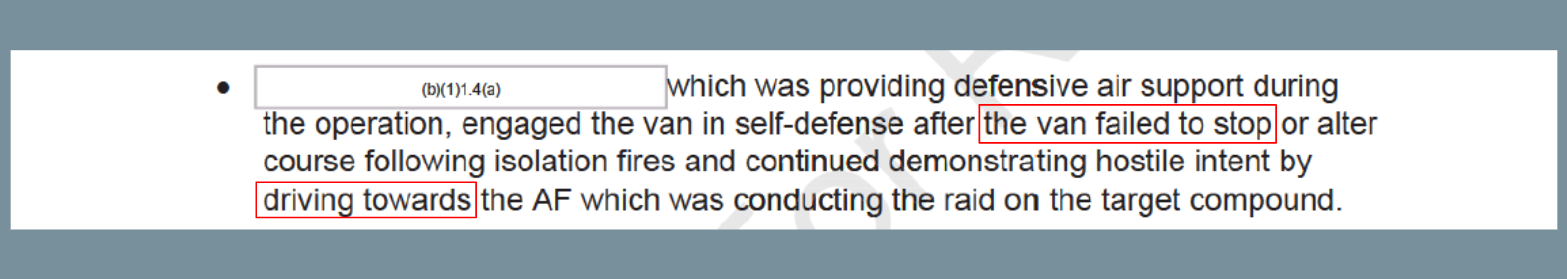

The assessment of the incident presents the “hostile intent” of the drivers by way of justification for the strike which reportedly killed and injured the civilian occupants of the vehicle.

Airwars’ review of US actions in Iraq, Syria, and Afghanistan has identified multiple similar cases where patterns of driving were seen as indicators of combatant status, with a “high rate of speed” or a “sudden turn” used as justification for strikes. In at least ten out of the 160 declassified ‘credible’ civilian harm assessments reviewed by Airwars, civilians were harmed after their response to warning shots was also interpreted as evidence of combatant status.

This includes a case in 2016, where the US-led Coalition fired aerial rockets as warning shots over the civilian drivers of fuel trucks in Syria. The declassified civilian casualty assessments reveal that these warning shots were not effective, and the vehicles were targeted anyway after “the driver of the vehicle did not exit the vehicle for the duration of the weapon system video”. As Larry Lewis of the Center for Naval Analyses pointed out to NPR in relation to the Baghdadi case, “They want the van to stop. But what do they use? They use lethal force … so you get this escalation based on misunderstandings.”

In the US military’s own civilian harm assessments into these cases conducted frequently before the 2019 assessment, assumptions of combatant status based on either driving style or responses to warning shots were therefore shown to be flawed. In DoD’s own 2022 action plan, one of the 11 objectives is intended to “incorporate deliberate and systemic measures to mitigate the risks of target misidentification”, noting that “misidentification, including misinterpretation and mischaracterization, can be a frequent cause of civilian harm”.

To date, the US military has rejected at least 2,663 incidents of civilian harm as non-credible. On July 28th, 2023, Representative Sara Jacobs introduced the Civilian Harm Review and Reassessment Act, which would require DoD to reinvestigate past allegations of harm and make appropriate amends.

Read more on our reporting on US military actions in Iraq and Syria here.