В період з 24 лютого по 13 травня 2022 року, під час вторгнення російських військ в Харківську область, від 275 до 438 цивільних осіб загинули внаслідок застосування вибухової зброї.

Дослідники “Airwars” задокументували всі повідомлення з відкритих джерел про завдану цивільному населенню шкоду і протягом короткого періоду, відомого як “Битва за Харків”, виявили 200 інцидентів заподіяної шкоди. Поміж щоденних повідомлень про загибель цивільних осіб, також повідомлялося про поранення більше 800 (за оцінками організації, до 829) цивільних осіб. У випадках, коли місцеві джерела надавали більше детальну інформацію про жертв, “Airwars” встановив, що щонайменше 30 дітей, 52 жінки і 61 чоловік були ймовірно вбиті російськими військами.

Це дослідження є, мабуть, найбільш грунтовною базою даних у відкритому доступі про шкоду, завдану цивільному населенню у густонаселеній Харківській області, що межує з Росією.

Спираючись на розповіді місцевих мешканців, журналістів та організацій громадянського суспільства, цей звіт проливає світло на повсякденне життя харків’ян під обстрілами. Нижче ми представляємо результати дослідження повідомлень місцевих джерел про шкоду, завдану мешканцям Харкова, пошкодженя критично важливої інфраструктури та перешкоджання наданню життєво важливих послуг. Ми також пропонуємо до вашої уваги наш аналіз інформаційного середовища та непересічних викликів щодо точного документування людських жертв у складних обставинах війни.

Битва за Харків

Наша робота з документування жертв серед цивільного населення враховувала всі повідомлення з місцевих джерел про шкоду, завдану цивільному населенню вибуховою зброєю, на території всієї Харківській області за період, коли місто Харків та його околиці були об’єктом інтенсивних бойових дій, інакше відомих як “Битва за Харків”.

Друге за розміром місто України, Харків, є одним з найбільш постраждалих міст під час війни. Розташоване приблизно за 40 км від російського кордону, з великою кількістю російськомовного населення і тісними зв’язками з російською економікою, місто було ключовою ціллю агресора з початку російського вторгнення 24 лютого 2022 року.

Коли російські війська вторглися в Україну з різних напрямків, тисячі військових увійшли до Харківської області. Міста і села зазнали сильних обстрілів. За кілька тижнів ключові міста області, зокрема, Ізюм, Куп’янськ та Балаклія, було окуповано російськими військами.

Сам Харків ніколи не був окупований, але, натомість, став ареною інтенсивних боїв. Багато мешканців покинули місто у перший місяць війни. За довоєнними оцінками, населення Харкова становило 1,4 мільйона осіб, але у березні 2022 року, за повідомленнями місцевої влади, кількість населення зкоротилась до лише 300 000. Проте успіх Збройних сил України в обороні Харкова відіграв значну роль у зміцненні морального духу в перші дні російського вторгнення.

Наприкінці квітня 2022 року українські війська почали контрнаступ на Харків. 13 травня російські війська були витіснені з околиць міста. Остаточний відступ росіян був описаний як один з найбільших успіхів української армії з часу, коли війська РФ відмовилися від наступу на Київ. У червні 2022 року, за оцінками міського голови Ігоря Терехова, населення Харкова повернулося до рівня близько одного мільйона осіб.

Тим не менш, більшість окупованих територій Харківської області було відвойовано лише в ході успішного українського контрнаступу у вересні 2022 року.

Сьогодні ситуація в Харкові в цілому спокійна, хоча періодичні російські обстріли міста та області тривають. Інфраструктура міста залишається зруйнованою, а спустошливий вплив російської агресії виявляється як у втрачених життях цивільного населення, так і у великій кількості місцевих мешканців, які досі не повернулися до своїх домівок.

Процес архівування

Наш новий архів містить важливі подробиці про те, де і за яких умов постраждало цивільне населення. Ці подробиці було встановлено на основі повідомлень місцевих українських джерел під час війни в Харкові.

Наше дослідження, здійснене на основі відкритих джерел, має стати відправною точкою для слідчих, журналістів, правозахисних груп, а також сімей та окремих осіб, які постраждали внаслідок цього конфлікту. Ми збираємо та зберігаємо всі місцеві свідчення заради утворення постійної бази даних про заподіяну шкоду. Дослідження ставить на меті також зберігти память про постраждалих внаслідок війни і дати зрозуміти потужним військовим формуванням у всьому світі, що завдана цивільному населенню шкода навіть в умовах інтенсивних міських боїв може і повинна бути зафіксована.

Наші оцінки завданої цивільному населенню шкоди не є остаточними, оскільки, враховуючи великі масштаби втрат серед цивільного населення, цілком імовірно, що не всі інциденти було охоплено джерелами, які ми відстежували.

Стислий опис нашої методології більш детально пояснює, як ми застосовували методологію реєстрації цивільних жертв в цьому густонаселеному і складному середовищі.

Частота та інтенсивність інцидентів завданої цивільному населенню шкоди

Протягом перших двох місяців російського вторгнення інциденти, пов’язані з нанесенням шкоди цивільному населенню, фіксувалися майже щодня. Цей інтенсивний період боїв за Харків був найбільш смертоносним для цивільного населення: лише за перші п’ять днів боїв було вбито від 18 до 38 цивільних осіб, а ще 119 отримали поранення.

В одному з інцидентів, відстежених “Airwars” 10 квітня, представник громади міста Золочів повідомив “Суспільному” телебаченню, що “з самого ранку Золочів обстрілювали майже весь день, а останні дві з половиною години – безперервно”. У квітні 2022 року мер Харкова Ігор Терехов описав місто як таке, що бомбардують “вдень і вночі“.

Навіть коли наприкінці квітня Збройні сили України витісняли російські війська з Харкова та його околиць, випадки завдання шкоди цивільному населенню було зафіксовано на решті території області: за день до того, як аналітики встановили перемогу України у битві за Харків, повідомлялося про загибель щонайменше двох цивільних осіб у результаті інцидентів за межами лінії фронту ЗСУ в Шебелинці, Дергачах та Балаклії.

Зазвичай цивільні особи були єдиними жертвами, про яких повідомлялося

Ключовою дискусією протягом війни було питання про те, якою мірою російські війська завдавали ударів по легітимних військових цілях. Російські офіційні особи звинувачують Україну в тому, що вона розміщує військові об’єкти поблизу цивільних населених пунктів, тоді як Україна стверджує, що ці удари є навмисно невибірковими.

Наші дані свідчать про те, що в 95% випадків, коли цивільні особи були вбиті або поранені (189 інцидентів), місцеві джерела повідомляли, що цивільні були єдиними жертвами російських дій і не згадували про інші військові об’єкти або українських військовослужбовців, яким було завдано шкоди.

Хоча оприлюдення інформації про втрати серед українських військових заборонено згідно з українським законодавством, що, можливо, пояснює відносно низькі показники військових втрат, цей висновок перегукується з іншими повідомленнями правозахисних організацій, таких як Human Rights Watch.

У трьох інцидентах повідомлення з місцевих джерел були суперечливими або неясними щодо того, чи були серед постраждалих також українські військовослужбовці, чи лише цивільні особи.

У одному з інцидентів, що стався 26 березня, російські війська обстріляли місто Барвінкове в Ізюмському районі, внаслідок чого загинуло щонайменше четверо українських солдатів і одна цивільна особа. Численні українські джерела, в тому числі в соціальних мережах, зазначали, що обстріл спричинив пожежу в загальноосвітній школі. Згідно з повідомленнями одного з джерел, що повязано з проросійським акаунтом у соцмережах, школа використовувалася українськими силами для створення “живого щита” для українських солдатів. Джерело наполягало на тому, що жертвами російської ракети стали військові. Наша методологічна записка більше детально розяснює те, як ми оцінюємо та враховуємо суперечливу інформацію.

Життя під обстрілами

Документуючи шкоду, завдану цивільному населенню, місцеві джерела надають унікальні свідчення повсякденного життя під час війни та висвітлюють далекосяжні наслідки агресії для цивільних.

Цивільні, які постраждалі від обстрілів під час перебування вдома

У щонайменше 60 інцидентах (що складає майже третину всіх повідомлень) цивільні особи були вбиті або поранені вдома внаслідок влучання російських артилерійських обстрілів або ударів у житлові будинки або споруди. В одному з інцидентів, що стався 17 березня 2022 року, мати та її чотирирічна донька спали у своєму будинку, коли почався обстріл. Джерела стверджують, що жінка накрила доньку своїм тілом, щоб захистити її. В результаті інциденту вона загинула, а донька отримала поранення.

Джерела повідомляли про цивільних, що загинули на своїх кухнях та у спальнях. Подробиці, надані місцевими ЗМІ, дають уявлення про втрачені життя: росіянки, яка жила в Харкові протягом десяти років; дев’яностошестирічного чоловіка, який пережив Голокост; двох сусідів, які збиралися разом пообідати – всі вони загинули в своїх будинках під час ймовірного російського бомбардування.

Місцеві джерела також зафіксували історії загибелі цивільних осіб, які намагалися врятуватися втечею. 6 квітня 2022 року повідомлялося про загибель 33-річного цивільного чоловіка після ймовірного російського обстрілу Золочева, Харківська область. Місцевий чиновник Віктор Коваленко заявив, що молодий чоловік біг “від свого будинку до підвалу сусідів” у пошуках притулку, “бо не мав власного. Він не пробіг і півтора метра – йому відірвало ноги вибухом”.

Порушення звичного ритму життя

За повідомленнями з місцевих джерел, деякі цивільні особи також були вбиті або поранені під час купівлі продуктів та інших необхідних речей.

28 лютого четверо місцевих мешканців, у тому числі дитина, були вбиті під час збору питної води після того, як вони полишили бомбосховище. 6 березня жінка отримала важкі поранення, стоячи в черзі перед магазином. А 24 березня під час одного смертельного інциденту, ймовірно, загинули шестеро цивільних осіб і ще до 17 отримали поранення внаслідок ймовірного російського обстрілу супермаркету.

Місцеві джерела зафіксували багато прикладів того, як трагедія обірвала або назавжди змінила звичне життя. В одному з інцидентів мати гуляла з донькою вулицею, коли, за повідомленнями, неподалік впав російський снаряд, вбивши її і серйозно поранивши доньку. В іншому випадку літня жінка, яка годувала котів у парку, була вбита в результаті ймовірного російського артилерійського обстрілу. Джерела також повідомляють, що матір двох дітей було вбито перед її будинком, коли вона розмовляла по телефону, повертаючись з магазину. Її сусідка розповіла “Суспільному”, що “якби вона прийшла на хвилину раніше, то, можливо, встигла б… Двоє дітей залишилися без матері”.

Повідомлялося також про постраждалих цивільних осіб, які чекали на громадський транспорт, їхали у своїх автомобілях або перебували на робочому місці.

У березні і травні, під час двох окремих інцидентів, кілька волонтерів і працівників зоопарку “Фельдман Екопарк”, розташованого на північ від Харкова, були вбиті або серйозно поранені в результаті російських обстрілів. Серед жертв був п’ятнадцятирічний хлопчик, який загинув під час спроби евакуювати тварин парку.

Руйнування міста

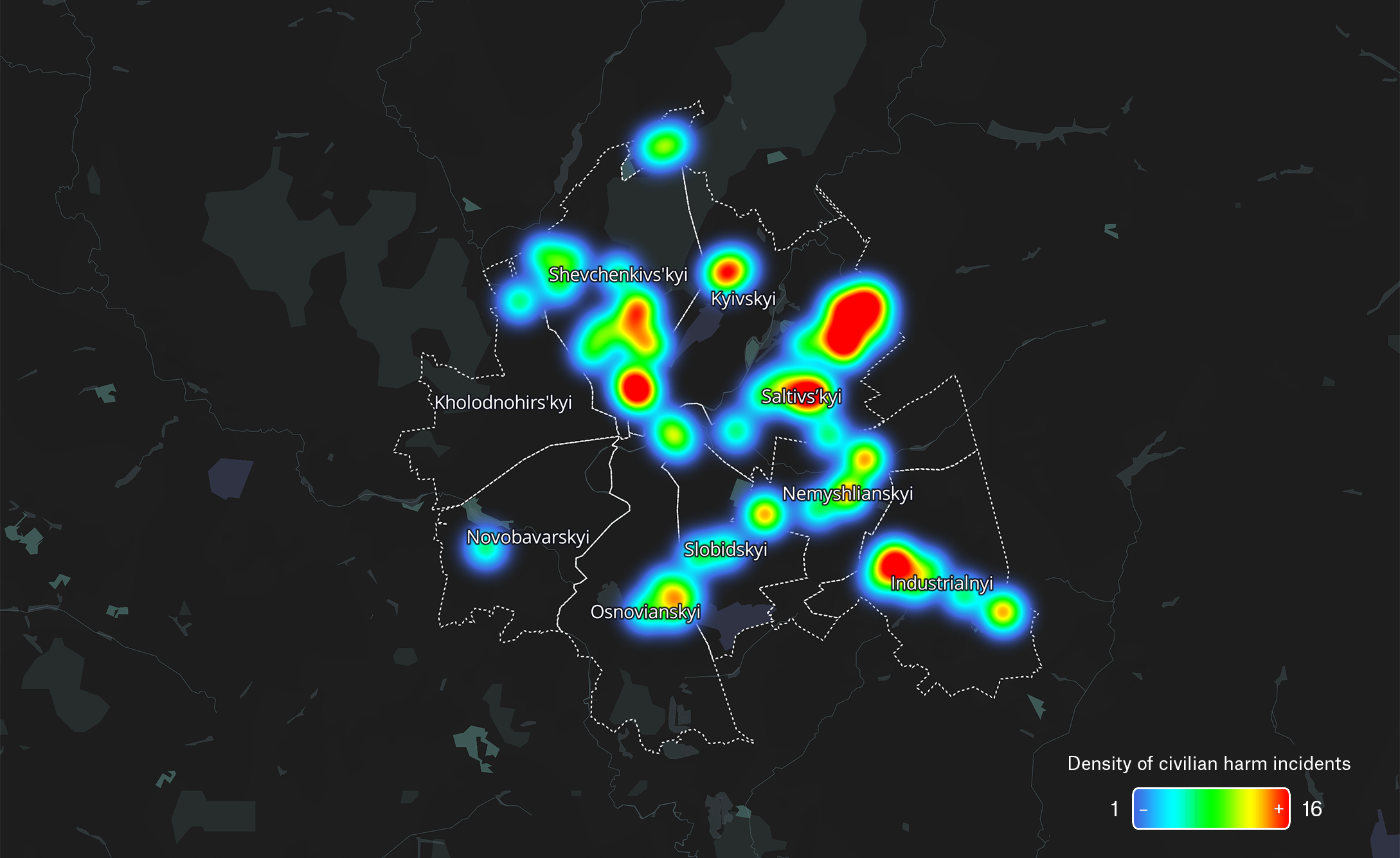

У Харкові найбільша кількість інцидентів, пов’язаних з завданням шкоди цивільному населенню, була зафіксована в Салтівському, Київському та Шевченківському районах та північній та східній частинах міста. У вересні 2022 року міський голова Харкова Ігор Терехов заявив в інтерв’ю, що “є житлові райони, де нічого не залишилося”.

За оцінками української влади, в Ізюмі, розташованому приблизно за 100 км на південь від Харкова і окупованому російськими військами понад шість місяців, було зруйновано від 70 до 80% житлових будинків.

“Airwars” встановив 56 інцидентів, в яких, окрім загибелі і поранень мешканців Харкова, також повідомлялось про пошкодження цивільної інфраструктури. В рамках цього звіту поняття “інфраструктура” визначається як будь-яка згадка наступних ключових термінів у джерелах: лікарні, школи, сільське господарство, служби доставки гуманітарної допомоги, шляхи гуманітарної евакуації, релігійні установи, ринки, системи енергопостачання (газо-, електро- та водопостачання).

Ми також відстежували пошкодження адміністративних будівель, магазинів, гуртожитків, парків, – включно з зоопарком, залізничних станцій, в’язниці та кладовища.

Відстежені “Airwars” інциденти, пов’язані з пошкодженням інфраструктури, відображають лише ті випадки, в яких також були зафіксовані смерті і поранення цивільних, і тому надають лише невеликий зріз більш масштабної картини пошкодження інфраструктури Харкова.

16 березня, за повідомленнями джерел, від двох до трьох цивільних осіб загинули і щонайменше п’ятеро, включно з трьома рятувальниками, отримали поранення внаслідок ймовірного російського обстрілу Новосалтівського будівельного ринку в Харкові. Джерела, які вдалося відстежити, не згадують про поранення військових або військові об’єкти, які було вражено.

Пошкодження і руйнування інфраструктури мали також опосередкований руйнівний вплив на життя цивільного населення. В одному з інцидентів, відстежених “Airwars”, після ймовірного російського удару було пошкоджено газопровід, що призвело до того, що понад 500 сімей тимчасово залишилися без газопостачання. В іншому інциденті, у травні 2022 року, 46-річну жінку було вбито на власному подвір’ї, коли вона готувала їжу на вогнищі через відсутність електрики.

Доступ до охорони здоров’я

Руйнування Центральної міської лікарні в Ізюмі після російського обстрілу 8 березня 2022 року, опубліковане у Facebook користувачем, чиє ім’я було відредаговано з міркувань безпеки

Серед “відстежених” Airwars інцидентів, пов’язаних з пошкодженням інфраструктури, найбільша кількість згадок стосувалася закладів охорони здоров’я, що безпосередньо впливало на доступ цивільного населення до медичної допомоги.

“Airwars” задокументував пошкодження 16 медичних закладів під час інцидентів, в яких також загинули або були поранені цивільні особи. Серед них – лікарні, центр донорства крові, аптека і машина швидкої допомоги. 3 березня сирійський лікар, гінеколог родом з Дейр-Ез-Зора, був убитий, коли, як стверджується, російський міномет влучив у Харківську обласну лікарню.

За схемою, подібною до тієї, про яку часто повідомляють у Сирії, “Airwars” також відстежила три випадки так званих “подвійних ударів”, коли за одним ударом слідує наступний в той час, коли аварійні служби або цивільне населення реагують на інцидент. Ці інциденти також були зафіксовані проектом “Напади на охорону здоров’я”, який задокументував випадки багаторазових ударів по одним і тим же лікарням у Харкові: “В одну лікарню влучили п’ять разів, а в іншу – чотири рази”. Представники проекту додали, що в період з лютого 2022 року по грудень 2022 року в Харківській області було зафіксовано найбільшу кількість пошкоджених або зруйнованих лікарень в Україні.

Документуючи шкоду, завдану цивільному населенню, місцеві джерела також часто повідомляли про те, що російські бомбардування ускладнюють здатність рятувальників реагувати на інциденти.

В рамках інциденту з завданням шкоди цивільному населенню, про який повідомлялося в березні, видання “Харків сьогодні” повідомило, що рятувальники “не змогли навіть під’їхати” до Харкова “через постійні залпи ворожої артилерії”. Місяцем пізніше, під час іншого інциденту в Ізюмі, російські війська, за повідомленнями, атакували евакуаційні автобуси, що призвело до жертв серед цивільного населення. Одне з місцевих джерел стверджувало, що через зруйновані дороги і мости, “а також через те, що російські окупанти забороняють пересування між селами в громаді”, було неможливо доставляти медикаменти та іншу життєво необхідну допомогу.

Зброя та боєприпаси, які використовувались

Бойові дії в Харківській області переважно відбувалися із застосуванням вибухової зброї.

Згідно з повідомленнями, більшість цивільних осіб загинули або отримали поранення від артилерійського вогню (77% зафіксованих інцидентів), тоді як у решті інцидентів шкоду було заподіяно авіаударами (вісім інцидентів) або боєприпасами, що не розірвалися (шість інцидентів).

Від 12 до 14 цивільних осіб загинули і від 4 до 11 отримали поранення від закладених вибухових пристроїв і боєприпасів, що не розірвалися. В одному з таких випадків джерела повідомили, що двоє чоловіків у віці 30 років загинули, коли їхній автомобіль наїхав на протитанкову міну по дорозі до села Чорноглазівка. Один з них збирався відвідати свою матір. За словами місцевого чиновника, вони “загинули на місці, машину розірвало на шматки. Окупанти нещодавно відійшли з цього села і могли залишити вибуховий пристрій”

Невелика кількість відстежених “Airwars” інцидентів, пов’язаних з мінами або іншими вибухонебезпечними предметами, не відображає масштабу забруднення землі в Харківській області. Шкода, пов’язана із забрудненням земель, вірогідно не обмежиться початковим періодом війни, і про неї ще буде відомо у майбутньому.

Головний прокурор Харкова Олександр Фільчаков пояснив виданню “AP News”, що “ніхто не може зараз сказати, який відсоток території Харкова заміновано, ми знаходимо міни скрізь”.

У 14 інцидентах місцеві джерела звинувачували російські війська у застосуванні касетних боєприпасів. Використання Москвою такої зброї в Україні широко задокументовано. У квітні 2022 року “Airwars” показав наслідки влучання одного російського касетного боєприпасу у лікарню та центр донорства крові в Харкові на другий день вторгнення. Повідомлялося про пошкодження в радіусі 350 метрів. Того ж місяця троє саперів загинули і ще четверо отримали поранення під час спроби знешкодити ймовірно російські міни. Міністр внутрішніх справ України Денис Монастирський заявив, що серед боєприпасів, які вибухнули під час операції, були касетні боєприпаси.

В одному з інцидентів місцеві джерела згадували про використання російськими військами снаряда, який впав на фабрику з парашутом, також відомого як “парашутна бомба“. Внаслідок цього інциденту, який, як стверджується, був здійснений Росією, загинула одна цивільна особа і ще шість отримали поранення. У квітні про застосування такої зброї в Харкові вже повідомляв мер міста.

Інформаційний простір

Відповідно до стандартної методології “Airwars”, всі інциденти класифікуються відповідно до характеру інформації, отриманої щодо інциденту: інциденти, де всі джерела згодні щодо причини і випадку шкоди, позначені як “підтверджені”, інциденти, де джерела не згодні щодо того, хто несе відповідальність або чи були жертви серед цивільного населення, позначені як “спірні”, а інциденти, де є дуже мало джерел або повідомляється лише загальна інформація, позначені як “слабкі”. Більше подробиць у нашій методологічній записці.

У Харкові “підтверджені” інциденти, в яких джерела звинувачували російські війська у завданні шкоди цивільному населенню, становлять 138 інцидентів, і відповідають за жертви серед цивільного населення у кількості від 275 до 387.

Наша команда також зафіксувала ще два “підтверджені” інциденти, в яких усі джерела приписували відповідальність за шкоду, заподіяну цивільному населенню, Збройним силам України. На ці інциденти припадає від двох до п’яти жертв серед цивільного населення. Оскільки ця доповідь зосереджена на ймовірних діях Росії, ці два інциденти не були включені до загальної кількості жертв, хоча вони продовжують розслідуватися нашою дослідницькою групою.

“Слабкі” інциденти охоплюють 60 інцидентів, в яких загинуло від 41 до 42 осіб. У всіх цих “слабких” випадках відповідальність за шкоду, заподіяну цивільному населенню, покладалася на російські війська. У двох інцидентах деякі місцеві джерела стверджували, що шкода була завдана Збройними силами України, які відтісняли російські війська, і “Airwars” виявила жертви серед цивільного населення.

Хоча занепокоєння щодо дезінформації широко розповсюджені, “Airwars” виявила, що окремі звинувачення у завданні шкоди цивільному населенню рідко оскаржувалися предметно зі сторони Росії. У тих випадках, коли звинувачення в завданні шкоди відкидалися або оголошувалися хибними (фейковими), ці заяви в основному зосереджувалися на загальних тенденціях.

В ході дослідження було виявлено, що джерела, які дискредитують заяви про шкоду, завдану цивільному населенню Харкова та області, зазвичай поширюють два основних наративи: або джерело стверджує, що шкоду було нанесено Збройними силами України, або що українські військові навмисно встановлюють військову техніку в житлових районах або на об’єктах цивільної інфраструктури.

У цьому контексті можна згадати й заяви Росії на найвищому рівні про те, що Збройні сили України використовували цивільних як “живі щити”. У березні 2022 року, після загибелі індійського студента у Харкові внаслідок російського обстрілу, президент Володимир Путін заявив, що українські силовики використовували індійських студентів у Харкові як “живий щит”.

Інші заяви, виголошені Міністерством оборони Росії, містять звинувачення в тому, що українські сили навмисно знищують цивільну інфраструктуру, щоб захистити секретну інформацію – наприклад, Фізико-технічний інститут у Харкові, в якому начебто розроблялися ядерні технології. 1 березня будівлю Харківської обласної державної адміністрації та площу Свободи в Харкові було обстріляно ракетою, що призвело до загибелі від шести до одинадцяти осіб, включно з дитиною. До 35 цивільних осіб, за повідомленнями, отримали поранення. Російські офіційні особи стверджували, що удар був навмисно нанесено українськими силами проти українських цивільних осіб, нібито “незадоволених міською адміністрацією”; тоді як президент України Володимир Зеленський заявив, що бомбардування здійснила Росія і що “на площі не було жодних військових цілей”.

Росія досі не визнала жодних жертв серед цивільного населення України, спричинених власними атаками, а в офіційних заявах, опублікованих Міністерством оборони Росії, неодноразово наголошувалось, що під російські обстріли та удари потрапляли лише військові об’єкти і так звані “бойовики”.

Критичні прогалини в обліку жертв

Основні відомості про зниклих безвісти осіб

У низці інцидентів наші дослідники зіткнулися з серйозною прогалиною в інформації, що є у відкритому доступі, – а саме, мало інформації щодо осіб жертв. В україномовних звітах було мало згадок про імена жертв, а також лише обмежена інформація про їхню стать, вік або рід занять.

Це кардинально відрізняється від інших конфліктів, за якими стежить “Airwars”, включаючи повітряні удари США в Ємені та Іраку, російські бомбардування в Сирії та ізраїльські бомбардування в Газі та Сирії.

Наприклад, за один інтенсивний місяць бомбардувань сирійського міста Алеппо російськими та сирійськими урядовими військами в липні 2016 року наша команда відстежила 76 різних інцидентів, в яких постраждало цивільне населення, і там ми встановили ідентичність 187 жертв. У березні 2022 року в Харківській області ми відстежили 70 окремих інцидентів, пов’язаних із завданням шкоди цивільному населенню внаслідок російських ударів, але загалом встановили ідентичність лише 37 жертв.

Існує декілька потенційних причин цього браку інформації. Ключовим фактором є політика України щодо захисту приватності, яку влада застосовує для захисту особистих даних цивільних осіб. Вона дозволяє оприлюднювати імена лише за згодою жертви або її/його сім’ї.

Україна є також державою з функціонуючими безпековими, розслідувальними, судово-медичними структурами та службами, які працювали над фіксацією завданої цивільному населенню шкоди ще з часів попередньої агресії Росії в Україні. В Іраку, Лівії, Сомалі та Сирії такі офіційні структури або відсутні, або викликають недовіру з боку цивільного населення. Таким чином, цивільні особи були змушені заповнювати прогалини – розміщувати інформацію про загиблих у соціальних мережах, зокрема, у Facebook.

Іншими причинами можуть бути безпекові ризики, пов’язані з документуванням завданої цивільному населенню шкоди в районах активних бойових дій, таких як Харків. Серед них, зокрема, ускладнений або заборонений доступ цивільного населення до зруйнованих будівель в пошуках своїх близьких через загрозу від нерозірваних боєприпасів, а також перебої в роботі Інтернету та/або електрики, які не дають місцевому населенню можливості передавати інформацію зовнішньому світу.

Зниклі безвісти

Місцеві джерела, які документують завдану цивільному населенню в Україні шкоду, вказують на ключові виклики зі збором точних даних про жертви серед цивільного населення через складнощі з пошуком та ідентифікацією жертв. В одному з інцидентів, відстежених “Airwars”, місцеві джерела повідомили, що минуло 20 днів, перш ніж жінку та її 11-річного сина знайшли похованими під уламками свого будинку.

Деякі експерти стверджують, що на пошук та ідентифікацію жертв серед цивільного населення можуть піти роки, а Харківська правозахисна група підрахувала, що лише в Харківській області зниклими безвісти вважаються майже 2 000 осіб.

Інформація щодо окупованих територій

Ідентифікація цивільних осіб, загиблих під час конфлікту, була особливо складною в Харківській області, оскільки багато районів були окуповані російськими військами протягом декількох місяців. Деякі інциденти, ідентифіковані “Airwars”, стали відомими громадськості лише після того, як українські війська відновили контроль над певними районами. Наприклад, в Ізюмі “Airwars” знайшла відкриті джерела, які описували загибель цілої родини в травні 2022 року, коли їхній автомобіль наїхав на ймовірну російську міну під час спроби евакуюватися з Харкова. Лише в жовтні 2022 року поліція змогла вперше повідомити про цей інцидент, відвідавши місце трагедії та опитавши місцевих.

Губернатор Харківської області Олег Синєгубов стверджує, що “перше, що вони [російські війська] зробили на окупованих територіях , – це відрізали людей від будь-якої інформації”.

В іншому інциденті, що також відбувся в Ізюмі 9 березня 2022 року, російські військові завдали авіаударів, а потім обстріляли п’ятиповерховий житловий будинок, що призвело до його обвалення. Внаслідок інциденту загинуло від 47 до 54 осіб, у тому числі багато сімей, які опинилися під уламками. Широкого розголосу трагедія набула лише у вересні, коли українські війська відновили контроль над цим районом.

У жовтні 2022 року українська влада повідомила, що знайшла понад 500 тіл на нещодавно відвойованих територіях. Причини смерті досі невідомі, а багато сімей все ще чекають на результати ДНК-тестів і додаткових розслідувань, щоб дізнатися про долю своїх близьких.

У багатьох інцидентах, зафіксованих “Airwars”, джерела згадували про розпочаті Харківською прокуратурою розслідування ще під час активної фази конфлікту. Результати цих розслідувань, ймовірно, розкриють нові подробиці про характер і масштаби шкоди, завданої цивільному населенню.

“Airwars” продовжуватиме оновлювати наш архів по мірі надходження нової інформації.

Висновок

Хоча масштаб жертв російської агресії ще досі не відомий у повному обсязі, інциденти завдання шкоди цивільному населенню, які були задокументовані в Харкові, вкотре демонструють руйнівний вплив конфлікту на цивільне населення.

Тяжкість людських втрат під час війни спонукає до посилення заходів із захисту цивільного населення під час конфліктів у всьому світі, особливо в густонаселених районах. Спираючись на місцеві джерела, можна припустити, що з огляду на масшаб і тяжкість завданої цивільному населенню шкоди, війна в Україні матиме далекосяжні та довготривалі наслідки.

(Translated to Ukrainian by Iryna Chupryna and Igor Corcevoi)

Основною мовою “Airwars” є англійська. У разі виникнення питань, пов’язаних з цим документом, будь ласка, перегляньте нашу англомовну версію тут або зв’яжіться з нами за адресою info@airwars.org