Share on

At least 127 civilian harm allegations in 'safe zone' in first week after evacuation order

Airwars’ investigator Sanjana Varghese spoke to NPR’s Ruth Sherlock about this investigation. You can read the article here.

On October 12th, the Israeli military issued a blanket call for all Palestinians living in the north of the Gaza strip to move south, saying it was “for your own safety”. More than one million people were told to flee, ahead of an expected ground invasion.

The evacuation zone started at Wadi Gaza, which runs through the centre of the Gaza Strip. In theory, civilians fleeing south of that line should have been safer, but Palestinians have reported extensive attacks in civilian areas in the central and southern parts of Gaza.

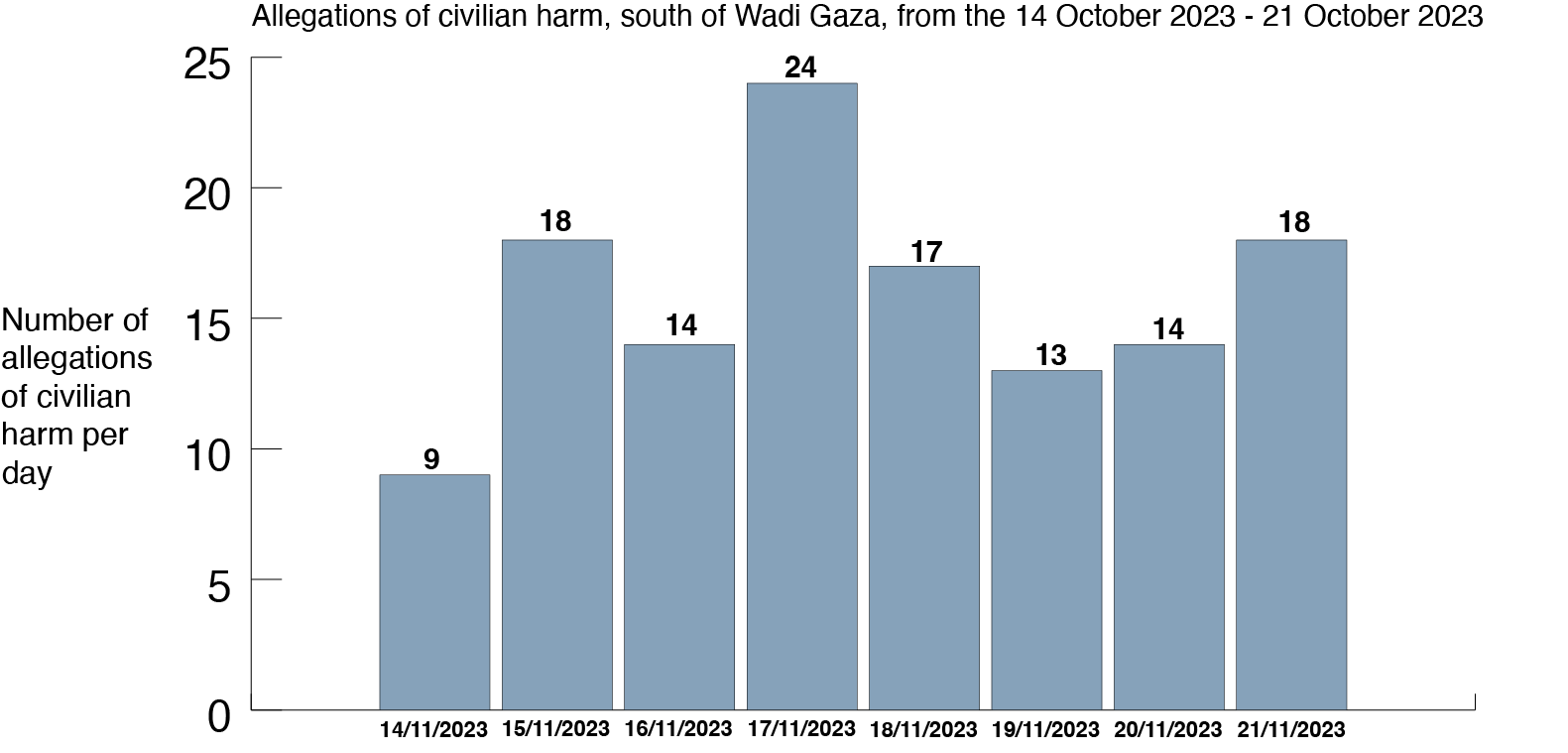

In the first seven days after the warning – from October 14th to 21st – Airwars’ investigation team tracked and geolocated at least 127 separate allegations of civilian harm from explosive weapons in this southern zone.

Amongst these strikes were many that allegedly hit densely populated neighbourhoods and civilian objects such as schools, hospitals and restaurants. The frequency of these allegations in this supposed safe zone suggests that there was no safe place for civilians in Gaza, despite assurances from Israeli authorities.

Safe to flee?

On October 7th, 2023 Hamas militants broke through the fence that separates Gaza from Israel and killed more than 1,000 people, according to Israeli authorities. In retaliation Israel has dropped thousands of bombs on Gaza ahead of a ground invasion, killing more than 10,000 people, according to Palestinian authorities.

Since October 7th, Airwars’ research team has been tracking every public allegation of civilian harm in order to provide an independent assessment of civilian casualties.

We have already tracked more than 1,000 separate allegations across the Gaza Strip alone; each allegation represents the death or injury of at least one civilian resulting from explosive weapons use. For the most part, these allegations are still being fully assessed by our research team – with additional sources identified, casualty ranges produced, and where possible details on civilian names and biographies captured. You can find full details of the around 40 published incidents here, and more about our methodology here.

But we have also been able to use these allegations to understand overall patterns of harm. By geolocating each harm claim from the week following the IDF’s instructions for civilians to move south, we have been able to pull together a comprehensive database of 127 likely Israeli strikes leading to allegations of civilian harm that occurred the week following the evacuation order. An allegation of civilian harm does not mean that just one civilian was injured or killed; these allegations often involve multiple people, as well as damage to buildings or family homes.

Map of civilian harm allegations, south of Wadi Gaza, between 14-21 October 2023. The red dotted line refers to the Wadi Gaza. Many locations include more than one alleged civilian harm incident. Sanjana Varghese / Airwars. Images via Maxar Technologies / Airbus / Google Earth.

We relied on news reporting, humanitarian agencies and organisations, open source documentation and relevant footage where necessary. We geolocated allegations to six levels of accuracy: area/region, neighbourhood, landmark/building, hospital, street, and an exact location. Any alleged civilian harm incident that we couldn’t geolocate was discounted from our dataset.

The distance from the Wadi Gaza to the Rafah Border Crossing on the southern border of the Gaza strip is roughly 27 kilometres. From east to west across the Gaza strip, the distance is around 6 kilometres at the narrowest point, and 12 kilometres at its widest point.

We found harm allegations on every day following the evacuation order. Just four days after the south was declared to be a safe area, the most civilian harm allegations were documented: twenty four allegations, suggesting at least twenty strikes in an area little longer than Manhattan.

In incidents that have been fully researched by Airwars’ research team, we found that in some cases strikes affected whole families as they sheltered together. In one incident, on October 21st, 2023, an alleged Israeli strike hit a Palestinian civil defence facility, alongside the Dahir family home, in Khirbet-al-adas, Rafah. Between six and ten people were likely killed in this strike and up to 11 injured. Of those killed, at least five were children from the same family, all aged 13 and under. Airwars assessors were able to cross-reference six of the individuals in this assessment with the dataset of names and individual ID numbers released by the Palestinian Ministry of Health (MoH).

In another incident on October 15th, in the al-Geneina neighbourhood in Rafah, the home of a doctor, Dr. Salah al-Din Zanoun, was hit. There were likely seven to eight people killed, all of whom were from the same family. Of those killed, Airwars assessors were able to cross-reference five of the individuals in this assessment with the dataset of names and individual health ID numbers released by the MoH.

We also found that multiple civilian objects – such as hospitals and schools – were hit in the south of Gaza. As people were told to move south – and around 700,000 people, according to the New York Times, did so initially – many took shelter in buildings such as hospitals and schools. In a number of cases large numbers of civilians were crowded together when strikes hit this infrastructure, such as a strike on a UNRWA school in al-Maghazi refugee camp, on October 17th. UNRWA said that around 4,000 people were sheltering at this school. The next day, an alleged airstrike hit another UNRWA school in Khan Younis – footage from the immediate aftermath clearly showed that groups of people had been using the school as a home, with clothes laid out over external railings around the school.

The scale of this campaign in Gaza makes this one of the most intense conflicts that Airwars has ever monitored – in just the first three weeks of the war, we monitored more individual incidents of harm than in any given month of any conflict Airwars has monitored: including deadly campaigns such as the war against ISIS. Our data also suggests that civilian harm is being compounded by the deteriorating conditions for civilians in Gaza, which is already one of the most densely populated areas in the world.

Clarifying note

Airwars uses a grading system to assess our allegations of civilian harm (you can read more about this here). Our assessments are being published in batches once they have been through the full review process.

Airwars has only tracked allegations of civilian harm – this means that there may be attacks with no public allegations of civilian harm which we haven’t included in our dataset.

Share on

Forensic analysis and expert analysts suggest Israeli strike likely cause

This article was originally published in the Financial Times and written by the paper’s correspondents, as well as Airwars’ Joe Dyke and Nikolaj Houmann Mortensen. The full article can be read here.

Just a day after Israel ordered 1.1 million civilians to leave northern Gaza, two blasts on Friday destroyed multiple cars driving along one of the enclave’s main roads south.

Videos of the aftermath verified by the Financial Times show 12 bodies of men, women and children in Salah-ad-Din street, which Israel later designated a ‘safe route.’ One of the explosions rocks an ambulance as it attempts to leave the scene with some of the injured.

To assess the competing claims, the FT worked with Airwars, a conflict monitoring group, as well as munitions experts to shed light on the nature of the attack, its timing, aftermath and type of explosive used.

Airwars/FT partnership finds facility at centre of Russo-Iranian UAV partnership recruiting specialist engineers and Farsi speakers

This article was originally published in the Financial Times and written by Airwars’ Nikolaj Houmann Mortensen and Sanjana Varghese, along with multiple reporters from the FT.

Russia’s covert drone partnership with Iran has included close co-operation on a new factory in the Russian province of Tatarstan, where Moscow has converted an agricultural unmanned aerial vehicle maker to supply its war effort in Ukraine.

Albatross, the company operating on a key site for Russo-Iranian collaboration, has produced reconnaissance drones for President Vladimir Putin’s defence ministry, with roughly 50 delivered for combat in eastern Ukraine.

The factory is at the centre of an expanding tech partnership with Tehran, whose expertise Moscow has relied on to establish a domestic drone-building capability to support its invasion and further skirt western sanctions.

Activity at the Russian facility has increased in recent months, with the business park where it is based launching a recruitment drive for UAV engineers and Farsi speakers able to translate “technical documents”, according to adverts and social media posts.

Albatross, a Russian group that previously specialised in farming tech, built its new factory inside the Alabuga special economic zone in Tatarstan — a site the US has claimed is the centre of the Tehran-supported effort to develop Russia’s capacity in making drones.

In a video released last month, Russia’s Ministry of Defence showed soldiers in Ukraine launching reconnaissance drones, which it referred to as “Albatross” drones. In a statement to Russian state media, the company said they had supplied 50 M5 drones. The drones appear identical to ones being built at the Alabuga factory.\

In February, the Institute for Science and International Security, a Washington think-tank, first reported that Albatross had established itself in Alabuga and they noted job advertisements had been placed in the area for UAV engineers.

From October 2022, the business park sought candidates for roles with titles such as “UAV production director”, “UAV designer” and “UAV chief technologist”.

Airwars, a conflict monitoring group based at Goldsmiths, a college of the University of London, found several ads for UAV-related jobs cited a requirement to understand “reverse-engineering processes”. In addition, they found the business park has also posted advertisements for Farsi interpreters who will be required to travel, perform simultaneous translation and translate technical documents.

In June, the White House issued satellite photographs that identified two buildings in the Alabuga zone area as a key part of Iran’s attempts to help Moscow increase its drone capacity. “We are also concerned that Russia is working with Iran to produce Iranian UAVs from inside Russia,” said John Kirby, the US National Security Council spokesperson.

The Financial Times and Airwars have identified Albatross as the drone-builder in one of those buildings. Statements by Albatross on the floor space of their facilities match the official dimensions of one of the buildings. In addition, an address listed on Albatross’s website seems to correspond to the location identified by the US photograph.

The article can be read in full here.

The research for this investigation was supported by a grant from the Investigative Journalism for Europe (IJ4EU) fund.

Share on

Investigation suggests a PKK bomb, rather than the Turkish military, may have killed two Iraqi holidaymakers in Kurdish region

On August 22nd 2021, security forces in the Kurdish region of Iraq came across a battered white Kia Sportage at the side of the road. In it, they found the bodies of two men.

Ahmed Shukr, 40, and Youssef Omar, 26, from the city of Mosul, were on holiday in the mountainous Darkar region of Zakho district, a popular retreat for domestic tourists seeking to escape the sweltering summer heat. They had been reported missing two days earlier.

While a place of leisure and relaxation for some, Iraqi Kurdistan is also in the midst of an ongoing conflict between the Turkish armed forces and the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), a Marxist militant group that calls for greater autonomy and increased rights for Kurds within Turkey. Seeking to crush the group, Turkish forces have expanded into parts of northern Iraq, backed by air and artillery strikes. Dozens of civilians have been killed in the fighting, with thousands displaced.

Almost all local sources attributed the men’s deaths last August to either a Turkish air, drone or artillery strike. At the scene Omer Jalal, a relative, told Rudaw: “You are in your own country and it is safe, but you get bombed by the Turks…. Where is our government?”.

Yet an Airwars investigation piecing together the final moments of the two men’s lives has found they were most likely killed by a roadside bomb, possibly planted by the PKK. One of the first such instances of civilians killed by such munitions in Iraqi Kurdistan, it could indicate a dangerous trend for those living in or visiting these conflict-affected areas.

The investigation also reveals how the spread of the conflict has resulted in a sharp rise of reported civilian harm in the Darkar region.

Verifying the video

On the morning of August 20th, Shukr and Omar apparently set off from their resort, keen to explore the rugged mountains.

At the outskirts of the village of Sharanish, the men took a turn, seemingly unaware they were entering a militarized area known locally as the “Red” or “Forbidden” zone. In recent years Turkey has set up military bases in areas previously largely unaffected by the conflict, including the area around Sharanish.

Farhad Mahmood, the mayor of Batifa sub-district, said that Iraqi border guards who had been manning a roadside checkpoint in the area mistook the tourist for locals and waved them through. Moments later that error proved fatal.

An explosion hit the car, which ultimately crashed into a rock. Local media alleged it had been hit by Turkish artillery fire or possibly a drone strike. “A Turkish artillery shell fell near their car,” a security source in the predominantly Kurdish area told the Shafaq News Agency.

But later that day a video, published by local media outlet Kurdistan 24, emerged that challenged the prevailing narrative.

It appeared to show a car driving along a rural road when an explosion rocks it. The car then drives out of shot.

The first challenge was to locate the strike and check whether the video showed the same explosion that killed the men.

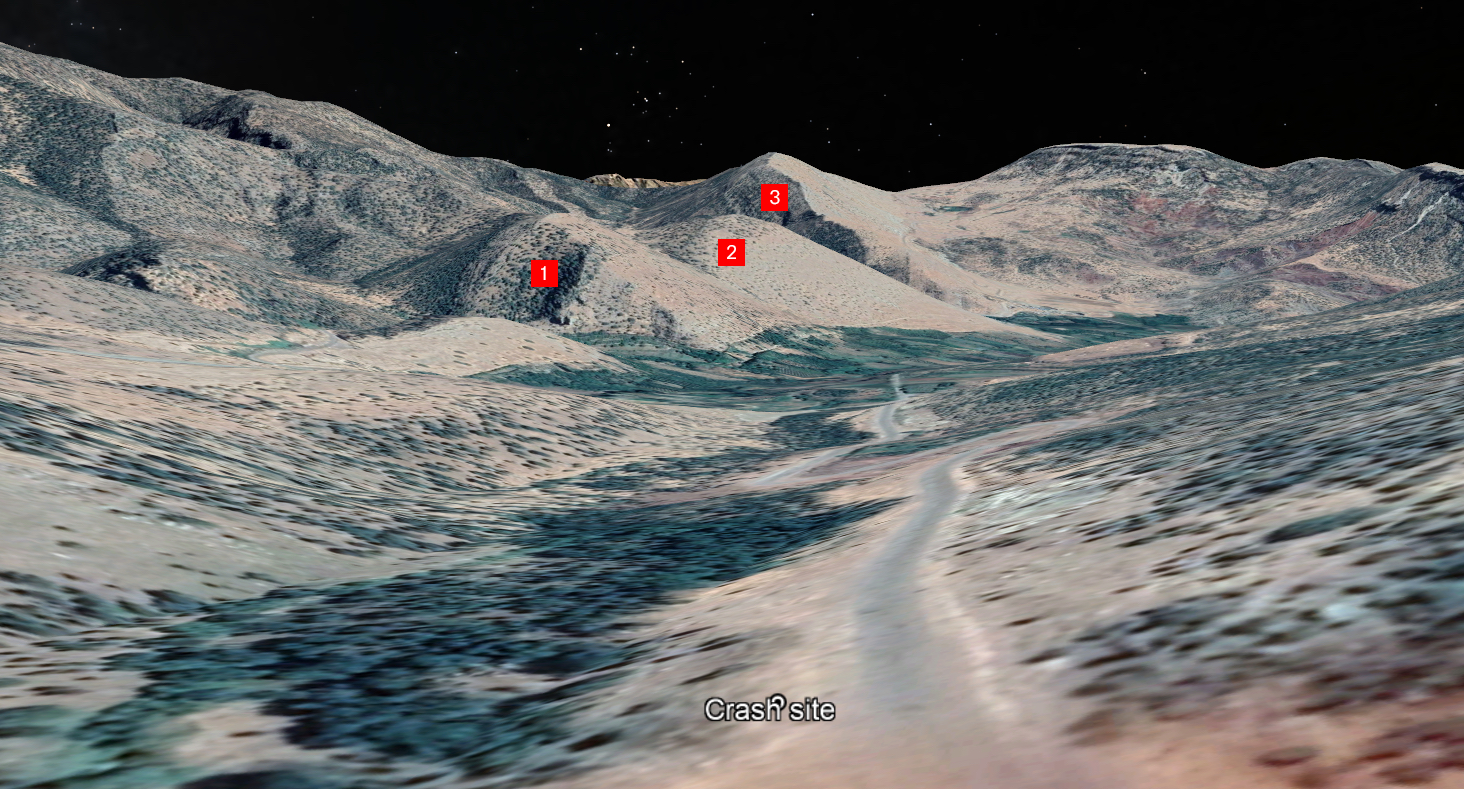

The road appeared to be in the base of a valley. A steep sparsely-vegetated hillside is visible to the right, while a low gradient heavily forested slope can be seen on the left. In addition to the distinctive contours of the road, an earthen bank runs along its left side. A structure is visible in the top right of the frame, indicated by a solid red box and the letter B. A cylindrical structure, seen closer to the vehicle, is indicated by a dashed red box and the letter A.

Having first identified features within the frame, finding the location using satellite imagery is considerably easier if you know where these features are in relation to one another (i.e north, south, east or west).

The fact it was sunny on the day the video was filmed helped with this process.

The size and orientation of the shadows generated by the explosion helped to identify both the approximate time of day, and the direction the car was traveling in.

After the explosion there is a dust plume perhaps 50 metres high, which generates a shadow shorter than its height – indicating the sun is high in the sky and therefore that the incident occurred around noon. Since the shadow appears to the right of the plume – and Iraq being in the northern hemisphere where at noon shadows orient north – this led to the conclusion the car was traveling from west to east.

Reports indicated the incident occurred close to the village of Banke. Using this information Airwars’ geolocation team was able to identify the below location as the site of the explosion. Structure B, seen in the video and highlighted in image 1, is also visible in satellite imagery. Structure A appears to have been built after November 2019, the date of the most recent, high-quality, publicly available satellite imagery of the area. From this, we are able to determine that the men were driving west to east on a stretch of road between the villages of Sharanish and Banke.

Satellite imagery of the blast site. Structure B, seen in the video, is also visible in satellite imagery. Structure A appears to have been constructed after November 2019 and is therefore not present.

Using Google Earth, we were then able to locate images of first responders loading the bodies of the two men into an ambulance.

The location is 500 metres from the strike, suggesting the car drove on, likely as the wounded driver attempted to keep it on the road, before eventually crashing.

An image of the men’s bodies being loaded into an ambulance suggested their vehicle continued down the road for a further 500m before crashing.

The video was reportedly filmed from a nearby Iraqi border guard position. Once the location of the strike had been confirmed, Airwars was able to narrow in on a possible location of the guard post.

IED not artillery

Having verified that the video very likely showed the explosion that killed Shukr and Omar, the question became what photographs and video could reveal about the strike.

Airwars approached two munitions experts to review the visual material available.

Chris Cobb Smith, a munitions expert and former Major in the British Army, said it was very unlikely to have been artillery fire from a nearby Turkish base. “Artillery is notoriously inaccurate and would seldom be used to engage a target like this,” he said.

Contortion to the bodywork of the car seemed to have been caused primarily by the force of the blast. Image courtesy of Kurdistan 24.

He noted that artillery strikes would typically result in the location, or in this case the car (below), being pockmarked by shrapnel, but there was very little evidence of this visible on its bodywork. Instead, the crumpling and contortion to the bodywork seemed to have been caused primarily by the blast effect.

Roger Davies, a former British Army ammunition specialist with decades of experience analysing explosions from both conventional munitions and improvised devices, said he was “95 percent certain this is an IED strike.”

A view of the side of the vehicle closest to the blast. Image courtesy of Shafaq News Agency

“The fragmentation damage could have been caused by a small amount of shrapnel, or by a metal container used to house the bomb, or stones and rubble thrown upwards by the force of the explosion, but it is not consistent with an artillery round,” said Mr. Davies.

Mr. Davies said the video and photographs suggested an IED weighing in the order of 5kg, likely initiated by a radio signal and laid above ground, a tactic commonly employed by those who want to limit the time they spend installing a device, “especially if they suspect they are under observation.”

Experts would have expected to see more widespread fragmentation damage to both sides of the vehicle in the event of a conventional munition strike. Image courtesy of Kurdistan 24.

Due to the colour of the smoke given off by the blast, TNT – a carbon-rich explosive commonly used in conventional munitions – was ruled out as a possible charge.

Questioned as to whether the car may have been targeted by a guided munition, Mr. Davies said he thought it unlikely, as neither the damage to the vehicle nor video footage showed evidence of such a strike.

The real target?

A cursory look at nearby mountains reveals why so many of the sources may have implicated Turkey in the strike, and why whoever planted the bomb may have chosen the location.

In the latter half of 2020, the area witnessed a significant military build-up, one that forced many local residents to flee.

In May 2021 resident, Ali Mahmoud, told Rudaw: “It’s (the Darkar area) on the main street. It’s a tourist place… people come and go and the situation was very calm… Two months ago the Turkish army and PKK ruined our situation.”

A suspected Turkish military position is seen before, and after, construction. (Images via: Sentinel hub.)

The arrival of Turkish troops in the area may suggest they were the intended target.

On November 4th 2020, one member of the Iraqi Kurdish security forces was killed and two others wounded when IEDs struck their vehicles in Chamanke sub-district in Dohuk. The People’s Defense Forces (HPG), the PKK’s military wing, accepted responsibility for the strike after it said government forces encroached on their self proclaimed area of operation. The attack resulted in condemnation of the PKK from the US, France and the federal Iraqi government.

Despite this, reported civilian harm in Iraq stemming from PKK IED strikes has remained low.

An escalation in reported civilian harm

Whether the deaths of Ahmed and Youssef were caused by an IED or some other action, it’s clear that risks continue for civilians in the region. Over the course of 2021, Airwars recorded four instances of civilian harm in the Darkar area, resulting in two civilian deaths and four injuries, a dramatic increase in comparison to previous years.

- On May 26th, two shepherds were injured by alleged Turkish artillery fire that struck the village of Behri. Video of the aftermath of the attack featured in a recent PBS News report.

- On August 10th Abdulrahman Yousif, 55, was seriously injured in an alleged Turkish artillery strike on Bosal village, according to the monitoring organisation Christian Peacemakers Teams. Mr. Yousif was reportedly picking figs in his orchard when he was targeted by artillery fire from a recently constructed Turkish military base. (As a single-source claim Airwars deemed the assessment ‘Weak”.)

- On December 27th, a 42-year-old woman was injured in an alleged Turkish air or artillery strike in the village of Banke. She was reported to be in a serious condition and was transported to Zakho hospital for treatment. One source alleged that the artillery fire originated from a Turkish military base in the area.

Prior to the base’s construction, Airwars had recorded just one incident of reported civilian harm in Batifa sub-district over the course of six years of monitoring – an alleged Turkish artillery strike that injured four civilians in 2017.

Conclusion

Airwars’ investigation into the events of August 20th suggests that Ahmed Shukr and Youssef Omar were killed by a roadside IED rather than by a Turkish military attack, as was widely reported at the time. While no party has claimed responsibility for the attack, suspicion may point to members of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) in a case of mistaken identity.

Data collected by Airwars also shows how a military build-up in the area resulted in a significant rise in reported civilian harm. In the past year, up to 36 civilians have been killed by alleged Turkish military actions inside Iraqi Kurdistan.

As the conflict spreads into more populated areas, there is a potential for the use of such IEDs to become a more commonplace feature of the conflict in northern Iraq, greatly increasing the threat already posed to civilians.

In the short term, the spread of the conflict has had far wider implications in terms of displacement. In a recent report by PBS News, a local official claimed that 24 out of 26 villages in Darkar have been emptied by fighting in the past two years.