Airwars data featured in detailed visual breakdown by The Sunday Times

This article was originally published in The Sunday Times after Airwars worked with their team to visualise the patterns of families killed in our archive of civilian harm in Gaza. The introduction is repeated below but the entire article is available here, and an archived version here.

Maisara al-Rayyes was in the prime of his life. At 30, he had just completed his medical studies at King’s College London as part of the prestigious Chevening scholarship, which brings “outstanding emerging leaders” to study in Britain, funded by the Foreign Office.

Returning to Gaza last summer to work with Doctors Without Borders, he married a fellow scholar, Laura Hayek, whom he described as “the most gorgeous and kind-hearted girl” he had ever met.

A social media post on September 12 shows him taking a selfie with James Cleverly, the foreign secretary, after al-Rayyes and other scholars were invited to discuss the challenges and aspirations of young Palestinians.

Two months later he and his entire family were killed.

The al-Rayyes family are one of at least 1,800 that the Gazan authorities say have lost multiple members. In some cases whole families are being erased, their surnames removed from the civil registry, the official government record of citizens.

In collaboration with Airwars, the British-based organisation that counts civilian casualties in conflicts around the world, The Sunday Times has collated the details of more than 150 families that have lost multiple members in the Israel-Gaza war.

These are some of their stories.

On October 13th a group of journalists near the Lebanese-Israeli border line were struck by two explosions within the space of a minute. Reuters journalist Issam Abdallah was killed and the others injured, with AFP’s Christina Assi permanently disabled. A top Israeli official said its forces do not deliberately target journalists but “we’re in a state of war and things might happen,” while pledging to investigate the incident.

In collaboration with AFP, Airwars conducted an in-depth investigation of the incident. Researchers reviewed hours of footage matching key details and moments from different cameras, consulted six experts about munition remnants from the site, interviewed the reporters involved and other civilians in southern Lebanon, assessed satellite imagery, and built a 3D model to understand the geography and chronology of the strike.

The investigation sought to answer three basic questions – what struck the journalists, where was it fired from, and were there any apparent military targets nearby?

The first strike came after reportedly-Israeli surveillance drones were consistently audible near the journalists. This strike killed Abdallah and injured Assi. The second strike hit 37 seconds later and struck only a few metres from the first. Munitions experts said this close proximity all but ruled out the possibility the strikes were not deliberate.

The remnants of one of the munitions, found at the site near to Abdallah’s body, was identified by multiple experts as a fin-stabilised tank round, commonly associated with the Israeli military. No other militaries active in this area are reported to use these munitions. Analysis suggests it was fired from the southeast of the journalists, inside Israeli-controlled territory. An apparent Israeli military vehicle was visible on low resolution satellite imagery in this area.

The journalists were clearly identified and remained in an open location throughout, with a clear line of sight to an Israeli military base for more than an hour before the first strike. There was no evidence of a military target, or militant activity, near the journalists throughout that time.

Both Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International investigated the incident independently of Airwars/AFP, and their findings corroborated those of this investigation. HRW concluded that the strikes “were apparently deliberate attacks on civilians, which is a war crime,” while Amnesty said the incident was “likely a direct attack on civilians that must be investigated as a war crime”. Israel did not respond to AFP’s request for comment in time for publication.

‘Clear site’

Around 4.30pm on October 13th, Lebanese news stations reported on a possible infiltration attempt by a Palestinian militant group into Israel, with retaliatory Israeli shelling in Lebanon.

Two journalists from Al Jazeera – Carmen Joukhadar and Elie Brakhya – were searching for a safe place to film the areas being hit by Israeli strikes. They stopped on a hill outside the village of Alma al-Shaab. From here they had a clear view, but were more than a kilometre away from the nearest Israeli base.

Brakhya knew the region well as he covered the 2006 war between Israel and Hezbollah, the militant group that dominates southern Lebanon. They chose the location as it was “clean… meaning it is not covered in trees, it can’t be [seen as] suspicious from a military perspective,” Brakhya said. “It would be difficult to have any military site there – it is a hill with two houses, nothing can be hidden there.”

At 4:54 pm Carmen Joukhadar did a live piece for Al Jazeera – the most popular Arabic-language news channel. Six days earlier, Hamas militants had entered Israeli territory and killed more than 1,000 people, sparking retaliatory strikes on Gaza in which thousands of Palestinians had already been killed. Millions across the Arab world were watching Lebanon to see whether tensions between Hezbollah – a Hamas ally – and Israel might tip into full scale conflict and spark a fresh front in the war. Joukhadar told the viewers the day had been calm, but Israeli shelling had begun in the past half hour.

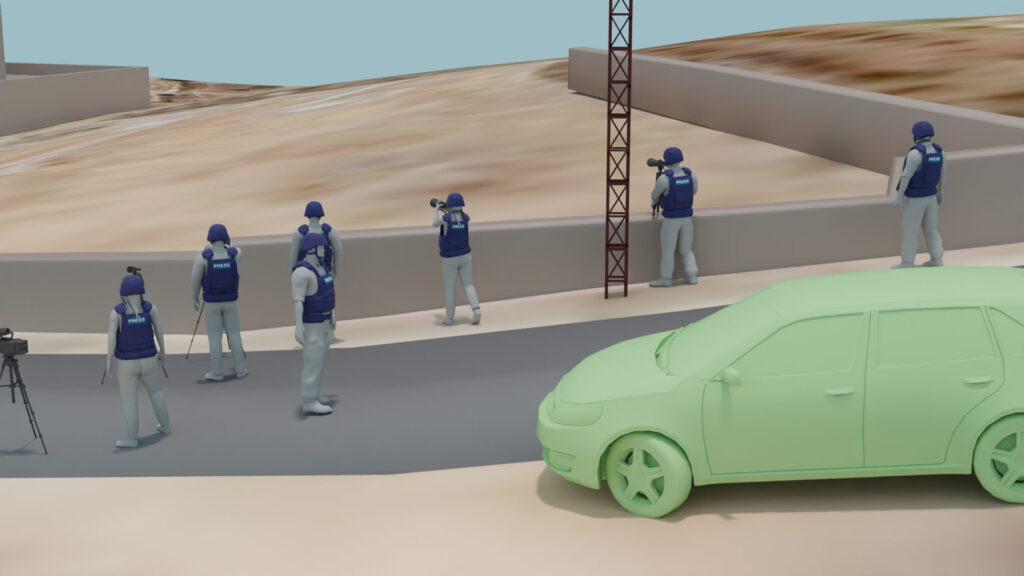

Shortly after, two AFP journalists and three from Reuters – two of the world’s largest news services – arrived at the site, joining the Al Jazeera team. Reuters had cleared the location with its security team, the journalists said. All seven of the reporters were clearly identified as such – wearing press vests and helmets. The Reuters car was also marked TV along the side and top.

In all of the footage reviewed by Airwars and AFP, there is no indication of military activity near the journalists. Airwars and AFP also interviewed six of the journalists at the site and each said they saw no military activity near them at any time. The nearest Israeli strike in the hour before was geolocated to around a kilometre from the journalists.

Between 5:30 and 6pm Israeli strikes intensified – with around 25 separate strikes heard on the journalists’ videos. Audio analysis conducted by three separate sound analysis firms for Human Rights Watch identified the sound of drones and helicopters hovering above the reporters in their camera footage. According to the audio analysis, a drone circled the reporters’ site 11 times in the 25 minutes before the first strike.

Military experts consulted by Airwars suggested that it was reasonable to assume the area was under continuous surveillance by the Israeli military.

“The newsgathering teams had been at that location for some time, were static, were wearing distinctive blue PPE (personal protective equipment) and obviously unarmed,” said Chris Cobb-Smith, a security consultant and former artillery officer in the British army. “I would expect the reporters to have been fully visible to the IDF.”

Cobb-Smith emphasised that the presence of Israeli surveillance drones further supported this observation. “A UAV would not only have located them, but with advanced surveillance capabilities they would easily be identified as media and therefore not a legitimate target,” he said.

A little more than two minutes before the first strike, the journalists noticed smoke rising across the valley on the Lebanese side of the border towards the west. To capture the scene they adjusted the angle of their cameras southwest.

AFP and Reuters were broadcasting live from the location and began filming the Hanita Israeli military base just over the border line – around 1.2 kilometres away. Around 6pm, an Israeli tank inside the base fired on a target inside Lebanon – several kilometres west of the journalists. In Reuters footage from the day, the tank can clearly be seen firing, and then moving to another location within the base.

Analysing the evidence

Using footage and testimony, Airwars and AFP reconstructed the scene to understand how the journalists were standing at the time of the incident.

Right to left: Thaer Al-Sudani (Reuters), Issam Abdallah (Reuters), Christina Assi (AFP), Maher Nazeh (Reuters), Elie Brakhya (Al Jazeera, back), Dylan Collins (AFP, front left), Carmen Joukhadar (Al Jazeera).

The first strike appears to have come from behind the journalists and hit the stone wall they were lined up along directly. Abdallah, who was positioned against the wall, was killed instantly. His body was pushed to the west towards the Hanita base, where it lay among the fragments of the wall. This suggests that the first strike originated from the east.

In photos from the scene, a large munition remnant can be seen amongst the debris of the wall – 2-3 metres from Abdallah’s body. It has been marked in blue in Airwars’ model.

An image of Abdallah’s body being taken away. The munition remnant is visible in the bottom left corner of the image (Image source: AlJadeed)

Airwars recreated the scene to better understand the geography of the attack

Airwars and AFP took images of the munition to six separate munitions experts. Each independently concluded the remnant was a 120mm fin-stabilised tank round of the type produced by an Israeli company and are typically used by the Israeli military. They are typically fired from Merkava tanks – a type used by the Israeli military.

Images of the munition: Source AFP

The Lebanese military, which operates in this area, and Hezbollah do not use this type of ammunition.

Similar munitions have been documented multiple times in Gaza, including after both the 2009 and August 2022 wars between Israel and Hamas, the Islamist movement which controls the Gaza Strip. Similar munitions have also been documented multiple times since October 7th, both in Gaza and Lebanon. In all cases, the strikes were Israeli.

“I am sure about this munition, because I have looked at those extensively and have photos of fragments looking very similar to that from previous Gaza wars,” said Chris Cobb-Smith, who conducted field research into previous conflicts in Gaza. He also provided Airwars with photos of tank rounds with a similar type of tail fins from Gaza in 2009.

An image of comparable munitions from 2009. Copyright: Chris Cobb-Smith

Israel’s military has confirmed it used tank and artillery fire in the area that day to prevent an infiltration from Lebanon.

Analysing the second strike

The second strike occurred 37 seconds after the first and caused a car belonging to Al Jazeera to explode, as well as seemingly leaving a crater on the road.

According to the reporters on the scene, before the strike the car was parked by the side of the road. After the strike, it had rotated almost 90 degrees, and a fresh crater created. The car showed signs of being impacted on its front left side.

Analysis conducted by Airwars suggests it is likely that the strike came in a low angle from the east and hit the front left side of the car before landing in the road.

The two strikes thus appear to have come from approximately the same direction.

Retired Irish Army colonel Desmond Travers indicated that the 37 second gap between the strikes aligns with the time it can take to reload a tank. He thus thought it was likely that both strikes came from the same tank and crew.

“It is most unlikely that this was a misfire or error,” said Travers, a former United Nations investigator in Gaza and former director of the Institute for International Criminal Investigations in the Hague. “It may be likely that the first round missed the vehicle, hence the firing of a second shell which achieved its purpose.”

Other arms experts highlighted that the impact on the front engine of the car suggests it was the intended target.

“If you are going to hit a car you always do an engine shot,” said a former British military Lieutenant Colonel, who asked to remain anonymous.

In photos of the crater from the second strike, several items are visible that could potentially be munition remnants. Two experts Airwars consulted pointed out that the remnants appear to be of a different type of metal than that from the first strike. One suggested that they looked like they could be from a smaller munition, including a missile.

However, none of the images was good enough quality to allow a definitive conclusion as to the munition type. Without access to munitions remnants, which are currently believed to be in the possession of the Lebanese authorities, it is impossible to determine exactly what weapons system or munition was used in the second strike.

Direction of first strike

With the munition from the first strike identified, it was necessary to pinpoint where it was fired from. The debris pattern of the wall blew debris 8-10 metres toward the west, with the remnant of the munition in this same location.

Wall debris blown towards the west. Image from Lebanese media SBI’s live feed from just after the strike. Abdallah’s body has been blurred. Copyright: Sawt Beirut International

This indicated clearly that the munition came from behind the journalists – the east. This conclusion was corroborated by all of the munitions experts Airwars consulted.

This ruled out the possibility of fire from the Hanita base itself – which was directly in front of the journalists. At the time of the strike, the journalists were facing southwest towards Hanita, where Israeli forces were striking targets inside Lebanon – located to the west of the journalists.

A vital clue came from analysis of the footage from the different news organisations. Around 45 minutes before the journalists were hit, both AFP and Reuters’ cameras captured the sound of a strike which prompted the videographers from both organisations to point their cameras southeast.

While Reuters’ camera seemingly captured the spot where the shell landed inside Lebanon, AFP recorded what appeared to be smoke after an outgoing strike originating from inside Israeli-controlled territory.

Airwars geolocated the smoke seen in the AFP camera, and it appeared to have come from the area near the Israeli village of Jordeikh. The location inside Lebanon that was hit was southeast of the reporters. This suggests that Israel was firing from the southeast in the same broad direction as the reporters, approximately 45 minutes before the reporters were hit. The site where the munition landed was about one kilometre from the journalists.

Satellite search

To seek to verify if there was an Israeli tank presence in the area near Jordeikh that day, Airwars and AFP sought satellite imagery of the area.

The US generally prohibits the sale of the highest-resolution imagery of Israel by American-based companies, and other governments have similar restrictions. However, Airwars obtained two lower resolution satellite images of the area around Jordeikh from that day via the satellite image providers SkyFi and Planet.

Even with lower resolution imagery, Airwars was able to identify armoured vehicles in the area by their shape and dimensions. The first image, captured at 11:06 am local time by Planet, showed the presence of at least one armoured vehicle near to the estimated origin of the strike. In the second image at 2:21 pm, by SkiFi, less than four hours before the journalists were hit, a military vehicle was observed at the side of the road just 30 metres from the area where Airwars estimated the 5:15pm firing could have come from.

The audio analysis conducted for Human Rights Watch examined the muzzle fire sound in the reporters’ footage and compared it to recordings from a nearby camera team of a Lebanese news channel. The analysis concluded that the shots came from a distance of 1.45 to 1.8 kilometres away. The object captured in the satellite image is 1.62 kilometres away.

The following morning, two vehicles were present at the same location on a satellite image provided by Planet. Due to the resolution of the images, a definitive identification of the vehicles is not possible, but the dimensions may correspond to that of Merkava tanks, according to assessment by open source researcher Gabòr Friesen and Airwars.

Two armoured vehicles on the following morning southeast of where the reporters were situated. Copyright: Planet Labs PBC

A worrying trend

This investigation, conducted by Airwars and AFP, found that the group of journalists were struck twice while carrying out routine journalistic work far removed from any military targets. The munition from the first strike was identified as a fin-stabilised tank round of the type typically used by the Israeli military. The images of the munition from the second strike are inconclusive. However its close proximity to the first – both in time and geography – and the presence of Israeli surveillance drones in the area, limits the possibility of an accident.

The evidence suggests the journalists were deliberately hit.

Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch have also conducted investigations into the incident independently to Airwars/AFP. The groups both concluded that the strikes were potential war crimes. Amnesty’s Aya Majzoub, Amnesty International’s Deputy Regional Director for the Middle East and North Africa, said their investigation found “chilling evidence pointing to an attack on a group of international journalists who were carrying out their work by reporting on hostilities.”

“No journalist should ever be targeted or killed simply for carrying out their work,” she added.

“This is not the first time that Israeli forces have apparently deliberately attacked journalists, with deadly and devastating results,” said Ramzi Kaiss, Lebanon researcher at Human Rights Watch. “Those responsible need to be held to account, and it needs to be made clear that journalists and other civilians are not lawful targets.”

AFP presented the findings of this investigation to officials. Israel did not reply to a request for comment by the time of release.

Since the attack, two further journalists in Lebanon are alleged to have been killed by Israeli strikes. On November 21st, two journalists working for the Al-Mayadeen channel were hit directly by a strike in southern Lebanon. More than 60 journalists have been killed in Gaza, Israel and Lebanon since hostilities broke out on October 7th, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists – the vast majority in Gaza. The first month of the war was the deadliest month for journalists since CPJ began gathering data three decades ago.

Editor’s note: This article was amended on December 8th to reflect the fact that Hezbollah has been known to use tanks, though not the kind of ammunition used in this strike. The original version said Hezbollah did not have tanks.

Share on

Survivors of the assault on the Al-Shifa hospital in northern Syria still seeking answers

A year on from a devastating assault on the main hospital in the Syrian city of Afrin, a new Airwars visual investigation has pieced together key features of the attack.

At least 19 people were reportedly killed in two strikes on the Al-Shifa hospital on June 12th, 2021 in what was the single deadliest incident tracked by Airwars in Syria during 2021.

Hospital attacks in Syria are sadly common, with both the Syrian government and allied Russian forces striking dozens of them since the civil war began in 2011. The US-led Coalition against the so-called Islamic State, Turkey and Kurdish groups have also all been accused of targeting medical facilities.

But the Al-Shifa hospital strike was unusual in that the survivors didn’t all identify the same culprit. Some accused the Syrian regime, others the Russians, while others still blamed the US-backed Syrian Democratic Forces or allied Kurdish militias. Some even claimed Turkey was responsible for an attack in a city under its influence.

By bringing together satellite imagery, CCTV footage, witness testimony and expert analysis, Airwars created a comprehensive visual assessment of the strike. We were seeking to understand what munition was used and where the rocket was fired from.

While the investigation was not able to definitively conclude which party was responsible, it did define a seven-kilometre wide region from where the rockets were likely launched. In that area the Syrian regime, SDF and Russians all operated.

“We hope that by publishing this investigation on the anniversary of this horrific attack, we will spark a new conversation about the brazen targeting of a hospital,” Emily Tripp, Airwars’ Director, said.

“This case is one of far too many in Syria’s long civil war where families are left seeking answers about who killed their loved ones.”

The full visual investigation is available here.

The context

Afrin is a geopolitically significant city – located at the forefront between multiple belligerents in the 11-year Syrian civil war.

The city is close to the Turkish border and is currently under the control of Turkish-backed groups that operate under the broad title of the Syrian National Army (SNA).

Turkey has fought significant conflicts with Kurdish groups, including the SDF – the closest ally of the United States in Syria. The SDF controls much of the territory to the east of Afrin.

At the time of the strike the Syrian government and its Russian backers also had military capabilities in the region, controlling territory to the southeast of Afrin, while also being known to operate in the east. Russian and Syrian government forces have been the most common strikers of hospitals during the civil war.

Al-Shifa hospital is located in the west of the city and is reportedly close to multiple Turkish government and SNA buildings. The hospital is partly run by the Syrian American Medical Society (SAMS).

At the time of the attack Turkish president Erodogan accused the SDF, who in turn accused Syrian government forces. Allegations were also made against Russian forces and even Turkey itself.

The strikes

Most investigations of this type begin by analysing the remnants of the missiles at the scene. However, according to medical sources on the ground, Turkish-backed authorities removed all shrapnel and other physical evidence from the hospital in the hours after the attack, and also prevented activists and media from accessing the site for several hours. Without these vital clues, we drew on other forms of evidence that might give us an idea of where the projectiles might have been launched from.

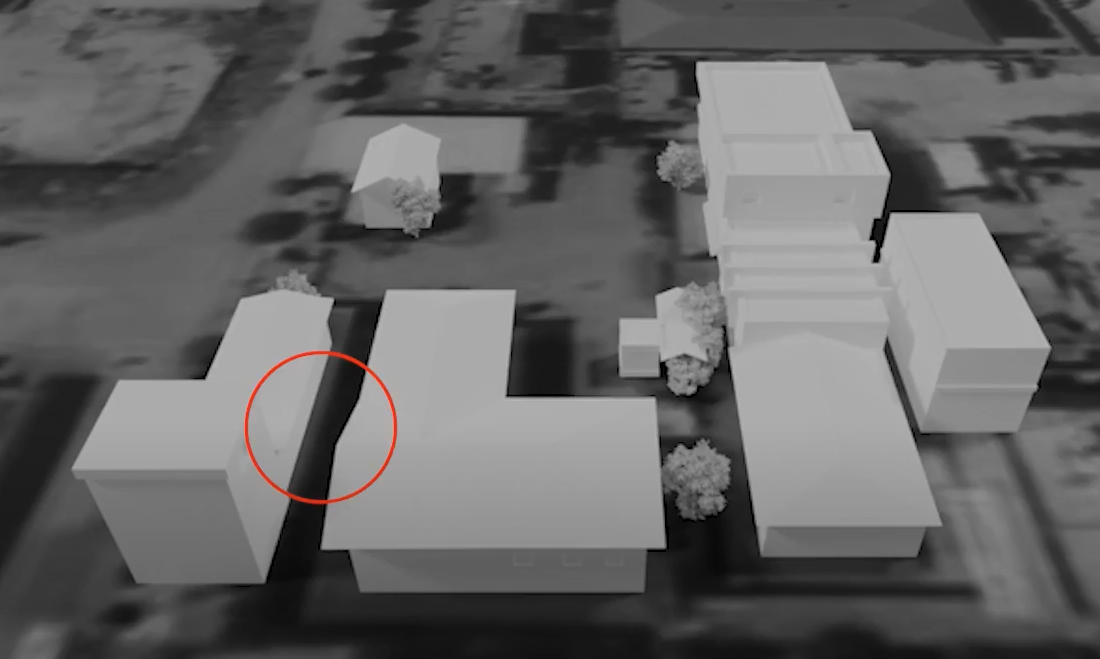

Airwars compiled all available visual evidence, including drone footage, CCTV recordings provided by SAMS, social media posts, photographs and satellite imagery. We also gathered witness testimony, including speaking to survivors. Using this information we produced a 3D model of the hospital, mapping the impact locations.

The first strike hit the alleyway of the emergency department at 6.55pm – CCTV footage captured the explosion before cutting out shortly after as the electricity failed. The strike caused significant damage to buildings on both sides of the alleyway and reportedly killed, among others, a woman giving birth.

“It was terrifying. It felt like an earthquake,” medic Mohammed al-Aghawani, who was injured in the attack, told Airwars. “At first I didn’t understand what had happened – whether I was alive or dead.”

The second strike, occurring a few seconds later, hit the main building and damaged the physiotherapy, paediatrics, ENT and surgical clinics. Photographs of the second impact location show a metal rafter broken and bent in half by the projectile as it penetrated the wall.

From this we determined that the projectile would have arrived at an angle perpendicular to the bend of the bar. Plotting this onto a wider map, we concluded that the projectile must have come from a near due easterly direction.

The third strike

Hoping to narrow down the potential launch area further, we extended our 3D model to map a third impact location allegedly from the same volley of projectiles. Dr. Amin Qosho was at sitting at his kitchen table in his apartment home a few hundred metres away from the hospital. Around 7pm a projectile struck the building opposite his apartment. Instead of penetrating the wall, it hit the building’s reinforced elevator shaft, sending a large spread of shrapnel towards Qosho’s balcony and through his door, killing him instantly.

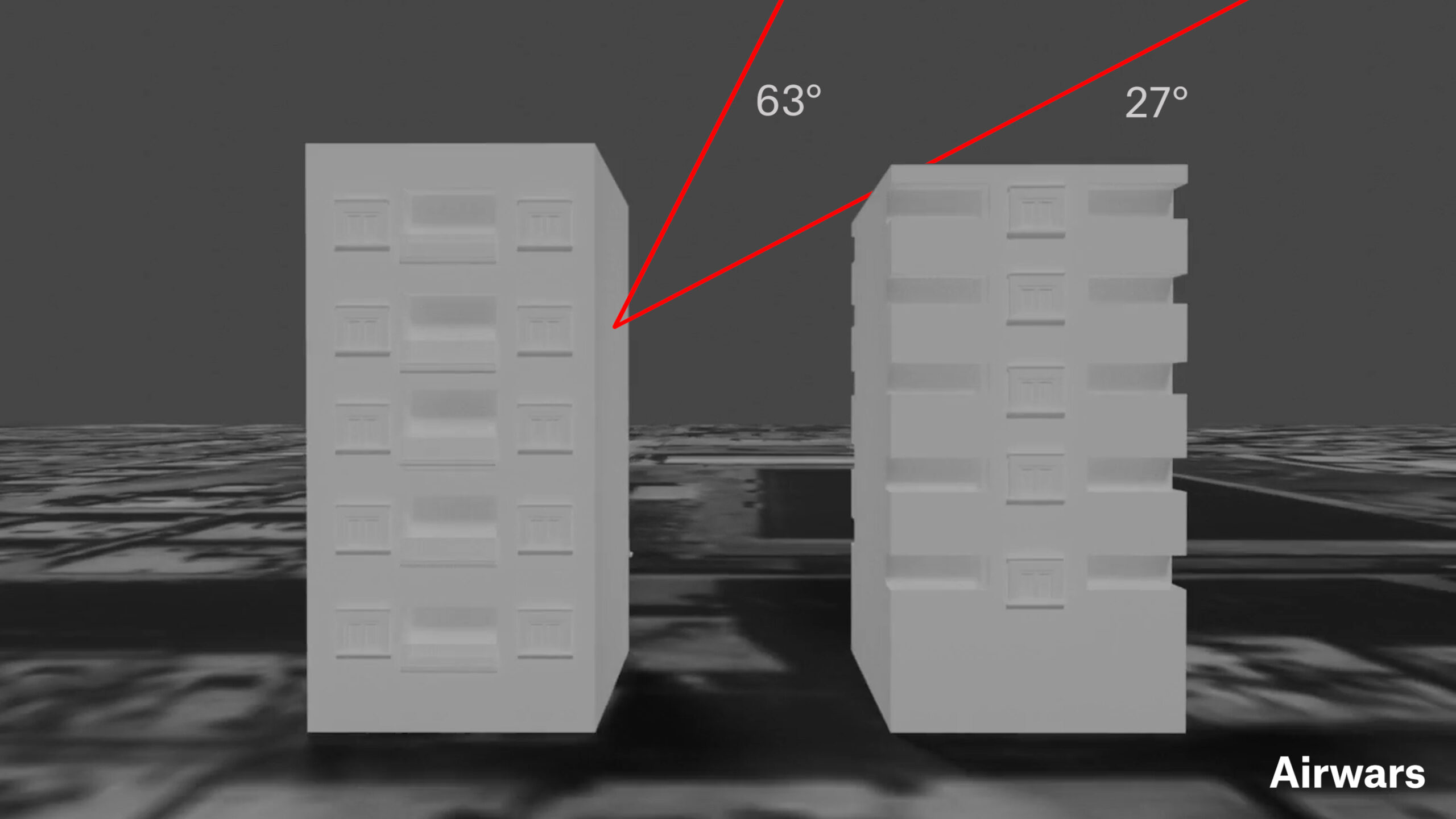

Using video footage and photographs of this impact location we were able to determine the relative height of the building struck and the building directly to the east. Building upon our previous determination that the projectile came from the east, we concluded that the angle of impact must have been high enough to clear the neighbouring building.

To narrow down our launch area further we investigated the munition used.

The type of weapon

While the Turkish-backed authorities removed all munitions remnants from the hospital itself, an image shared on social media that day showed a projectile found between Qosho’s home and the Al-Shifa hospital.

Images showing part of what appears to be remnants of a 122mm BM-21 rocket (spring-loaded fins) taken ~175m from the site of the Afrin hospital attack that killed over a dozen. Possibly from the first part of the double tap strike, hitting surrounding area

36.509510, 36.860433 pic.twitter.com/w8PAUvsTYU

— McKeever (@AKMcKeever) June 14, 2021

The projectile was identified as a 122mm, fired from a BM21 GRAD rocket launcher. This type of launcher was first developed by the Soviet Union in the 1960s but are now a very common – used by multiple sides in the Syrian war. Such launchers fire up to 40 projectiles in a single volley and are inherently inaccurate – designed for open battle fields not urban warfare.

While it was impossible to say with absolute certainty that the hospital and Qosho’s home were also hit by 122mm rockets, it is likely they were from the same volley of rockets.

Firing tables for GRAD rockets give a typical range of between 5 and 20 kilometres. However, using our model we determined that to clear the top of the building to the east, the rocket would have had to enter at a minimum of 23.4 degrees. This narrowed our potential launch area down further to between 12.3 and 20.5 kilometres.

We shared all our visual evidence with a leading world expert in GRAD rockets, Ove Dullum. He agreed that the projectiles came from an easterly direction, adding that the fragment patterns from the impact indicated a low angle of impact, narrowly clearing the neighbouring building to the east.

Compiling his analysis with our own findings we estimate that the rockets were likely fired from the east and within the closer half of our range.

Other investigations have found that the same type of rockets have been launched from the same area, including one by @obretix on a strike that hit the headquarters of a medical first responders organisation in Afrin six weeks after the attack on Al-Shifa hospital.

Conclusion

At the time of the incident, our estimated launch area was mostly under control of the SDF, America’s closest ally in Syria, along with allied militia groups. However control of this region is complicated. Reports in the weeks prior to the attack showed evidence of Russian and Syrian military forces operating within our estimated launch area.

On the 2nd of June, alleged Turkish artillery targeting SDF positions in Mara’anaz reportedly killed a Lieutenant in the Syrian militant, showing the presence and proximity of both the SDF and Regime forces in the area. Two days prior to the Al-Shifa attack, three soldiers from the Syrian military were reportedly injured by alleged Turkish bombardment on Menagh airbase, located within our potential launch area.

As such official designation of responsibility remains unclear. The SDF, Russians and Syrian Government all deny responsibility for this attack on a vital resource.

For the families of the victims and the survivors, the lack of accountability makes the suffering harder.

“I tried to check on the families of the martyrs – their psychological and financial situations are very bad,” Al-Aghawani said. “Personally, every few nights I dream of bombing.”

Airwars invites anyone with additional information to come forward.

Share on

Share on

Single strike may cause 350 metre span of damage, new Airwars visual investigation finds

A single Russian cluster munition that struck a hospital and blood donation centre in Ukraine likely caused lethal damage spanning 350 metres, a new Airwars visual investigation has found.

During Russia’s ongoing invasion of Ukraine, its use of cluster munitions has been widely documented. More than 100 countries have signed a UN convention banning their use, though Russia, Ukraine and the United States are among the nations yet to sign up. Such weapons are often described as indiscriminate. However on the ground, evidence of exactly how widespread their effects are can be are often hard to document. Yet a recent strike on the snow-covered grounds of a Ukraine hospital presented strong visual documentation.

Using uniquely placed, open-source videos, Airwars created a 3D model of all recorded damage locations when a cluster bomb hit the children’s hospital and a blood donation centre in the Ukrainian city of Kharkiv. One civilian was reportedly killed while waiting in line with his family to give blood, while hundreds of sick children took refuge in the hospital’s bomb shelters.

The Airwars investigation documented a total of 26 impact sites spanning 350 metres. Additional impacts likely took place in unfilmed areas around the sites.

Cluster munitions can have an impact range from around 100 metres – roughly the size of a football field – to multiple times larger, depending on the height at which they detonate. Their use by Russia has been documented multiple times in Ukraine, including in-depth analysis by Armament Research.

Several munitions experts whom Airwars consulted said the wide distribution of damage at Kharkiv could suggest that Russia is detonating cluster munitions at a higher altitude than normal.

Experts said that while the video showed a wide distribution of impacts, the number of submunitions documented was consistent with potentially being a single rocket. Definitive verification would only be possible with access to the site and to munition remnants.

“It has long been known that cluster munitions are indiscriminate, but this investigation highlights the sheer scale of suffering a single strike can cause,” Emily Tripp, incoming Airwars director, said. “While more than 100 countries have banned their use, many of the world’s largest militaries still refuse to do so – despite the inevitable risk to civilians.”

How the investigation was conducted

The cluster munition strike took place on February 25th, the second day of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Russian forces had advanced quickly on Kharkiv, Ukraine’s second city, in the northeast of the country.

In the afternoon, local reports first emerged of a devastating attack on a children’s hospital. The first video to emerge online, shot from a car dashcam, captured the moment the cluster munitions impacted on a road just outside the hospital grounds. It was timed-stamped at 16.41. Airwars was able to document and geolocate nine explosions in this video.

A second video filmed shortly after the attack meticulously documented each impact site inside the hospital grounds. Snow coverage enabled clear images of the different impact locations, again allowing them to be geolocated and mapped. In total Airwars investigator Imogen Piper was able to document a total of 25 craters.

In addition, the video showed one unexploded submunition found right outside the hospital entrance. This was a crucial clue, enabling us to identify the type of munition. Multiple weapons experts said it was a Russian made 9N235 or 9N210 cluster submunition – the two are visually identical.

There are two types of rocket capable of delivering these submunitions: the, 220mm 9M27K Uragan; and the 300mm 9M55K Smerch, which carry 30 and 72 submunitions respectively.

Munitions experts told Airwars that Russia is more commonly using 300mm Smerch rockets during the Ukraine conflict; and that their larger firing range of up to 70 kilometres also corresponded to Russian military positions at this time, north-east of Kharkiv.

Whilst 350 metres is a large distribution range for a single rocket, the experts said it was still within the parameters of a single 300mm rocket attack. They added that such rockets can be released at a higher altitude to increase the spread of submunitions.

As the video documents, this makes such cluster munitions relatively ineffective if trying to hit a specific military target. Instead, as Russia’s brutal assault has shown, they cause terror and devastation among civilians, with little military benefit.

Share on

Residents of a Gaza apartment block recall the frantic minutes before their homes were turned to rubble

This article was originally published as an interactive piece in The Guardian, co-written and researched with the Airwars Investigations Unit. It later won an Amnesty Media Award.

During the 11-day war between Israel and Palestinian militants in May 2021, Israeli airstrikes destroyed five multi-storey towers in the heart of Gaza City. The images of buildings crumbling to the ground flashed across TV channels around the world as Gaza faced the most intense Israeli offensive since 2014. At least 256 Palestinians were killed, including 66 children, and 13 in Israel, including two children. Israel claimed it was destroying the military capabilities of Hamas, who had fired rockets at Israel after weeks of tension in Jerusalem over the planned displacement of Palestinian residents and police raids on al-Aqsa mosque during Ramadan.

Each time Israel said it was targeting Hamas and that it had warned the residents first. But what is it like to have only a few minutes to evacuate before watching your life collapse into rubble?

In conjunction with the civilian harm monitoring organisation Airwars, the Guardian spoke with dozens of residents and gathered footage and photos to piece together the story of one building, al-Jalaa tower, demolished by an Israeli airstrike on 15 May 2021. These are the stories from inside the tower, of the Mahdi clan, who owned and lived in the building, the Jarousha family and the Hussein family.