Numerous international forces have intervened in Yemen in recent decades, including US strikes against Al-Qaeda and a deadly Saudi-led air war against Houthi rebels. Since 2023, the UK, US and Israel have attempted to further destabilise Houthi forces after the group launched attacks on Israel and Red Sea shipping routes in response to Israel’s war on Gaza.

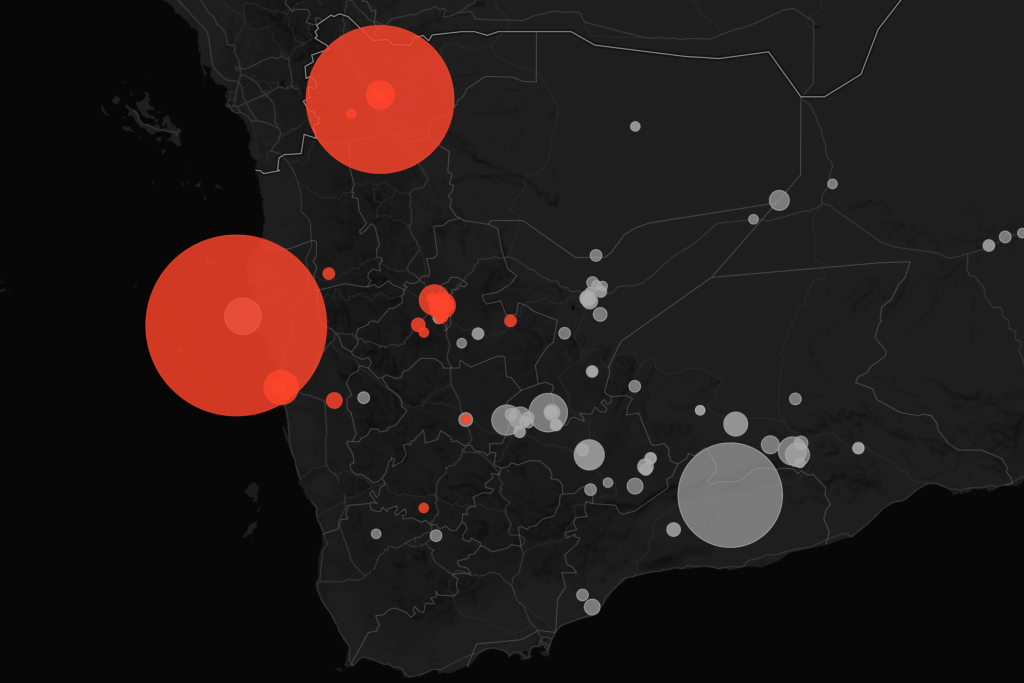

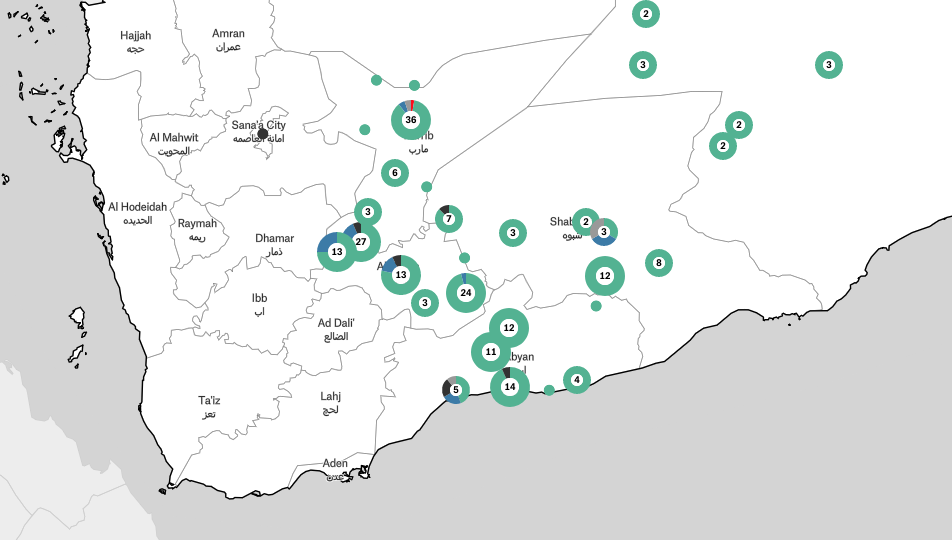

Airwars has documented all US strikes in Yemen, as well as foreign intervention on Houthi targets related to the war in Gaza, and conducted investigations and research.

Conflicts monitored involving Yemen