Share on

Almost 800 previously secret US airstrikes in Afghanistan during 2020 and 2021 are revealed, as US military declassifies data.

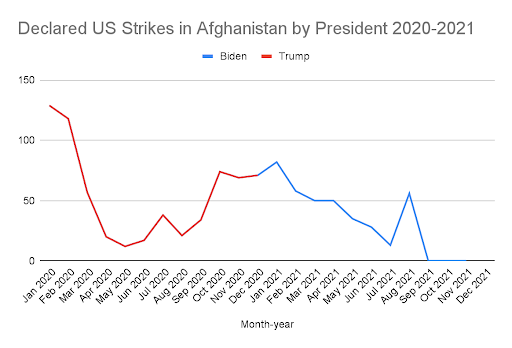

The release of classified records of recent US airstrikes in Afghanistan has revealed more than 400 previously undeclared actions in the last months of Donald Trump’s presidency – and at least 300 more strikes ordered by Joe Biden’s administration.

Even after the United States and the Taliban signed an effective peace agreement in February 2020, the US continued secretly to bomb Taliban and Islamic State targets, the data shows. And during 2021 – as the Taliban continued to ramp up attacks on Afghan government forces, and advance on Kabul – more than 800 munitions were fired by mostly US aircraft.

The crucial Afghanistan monthly data by Air Force Central Command, or AFCENT, was stopped in March 2020 after the Trump administration agreed an effective ceasefire deal with the Taliban. Those public releases showed how many strikes the US and its international allies carried out in Afghanistan as well as details of weapons fired, and had been released monthly for nearly a decade beforehand.

At the time the US Air Force said it was stopping the releases due to diplomatic concerns, “including how the report could adversely impact ongoing discussions with the Taliban regarding Afghanistan peace talks”.

The newly declassified data adds credence to allegations at the time that the United States may have secretly upped its strikes in Afghanistan to put pressure on the Taliban during negotiations taking place in Qatar, with sometimes devastating impacts for civilians.

While the United Nations was seemingly convinced that US strikes had largely stopped, the Taliban accused the US of violating the terms of the agreement “almost every day.” Those claims are now more likely to be taken seriously.

“These data tell the story of America’s struggle to end its longest war,” Graeme Smith of International Crisis Group told Airwars.

An air war that never ended

The US and the Taliban signed a so-called ‘peace’ arrangement on February 29th 2020. This did not explicitly commit the US to a full ceasefire, but involved the Taliban effectively committing not to attack American forces in Afghanistan during a proposed 14-month US withdrawal period.

It was also assumed that US strikes would also significantly wind down, and be focused primarily on self-defence actions. Yet the newly released AFCENT data shows US attacks never ceased, with 413 ‘international’ airstrikes between March and December 2020 alone.

Declassified AFCENT data has revealed almost 800 previously undeclared airstrikes conducted in Afghanistan during 2020 and 2021

Following the US-Taliban agreement in February 2020, official ceasefire talks then began in Doha in September of the same year between the Taliban and the Afghan Government. Yet in the same month, we now know, the US still secretly conducted 34 airstrikes.

Continuing US actions coincided with Taliban onslaughts on the outskirts of the cities of Kandahar and Lashkar Gah. The Taliban argued that these assaults, on Afghan government forces rather than American ones, were not in breach of the agreement but the US disagreed, Smith said. “That is why you see a sharp uptick in airstrikes from October 2020 as the Americans desperately tried to defend those provincial capitals,” he said.

Amnesty International recently highlighted what it believed was a US airstrike on Kunduz in November 2020 which killed two civilian women, Bilqiseh bint Abdul Qadir (21) and Nouriyeh bint Abdul Khaliq (25), and one man, Qader Khan (24). Munition fragments recovered from the scene pointed clearly to a US strike. It is now clear that the United States secretly conducted 69 strikes in Afghanistan that month alone.

Since assuming office in late January 2021, Joe Biden initially oversaw a slight drop in strikes before a significant increase, as the 20-year US occupation ended in a chaotic and devastating withdrawal.

In the final desperate three months of the US presence, 226 weapons were fired in 97 airstrikes by US (and possibly allied) aircraft in a doomed bid to halt the Taliban’s lightning advance. Many of those actions were likely to have been close air support strikes aiding Afghan National Army forces in urban areas, who were being overrun. The known risk of high civilian casualties from such actions has long been known.

In the chaotic last days of the war, dozens of civilians and 13 US military personnel died in an ISIS-K suicide attack as US forces barricaded themselves inside Kabul airport and desperate Afghans flocked to the site hoping to flee the country.

And in the final airstrike of the US occupation, 10 civilians were killed when American drone operators confused a father returning to his family home with an Islamic State terrorist. Last week, the Pentagon announced no disciplinary action would be taken in that strike.

United Nations deceived?

Stopping the release of monthly airstrike data in early 2020 also appears to have convinced the United Nations that the US was no longer conducting significant attacks.

In both its 2020 annual report on civilian casualties in Afghanistan and its 6-monthly report for the first half of 2021, the United Nations Assistance Mission to Afghanistan (UNAMA) played down the impact of US and international strikes – believing them to have mostly ended.

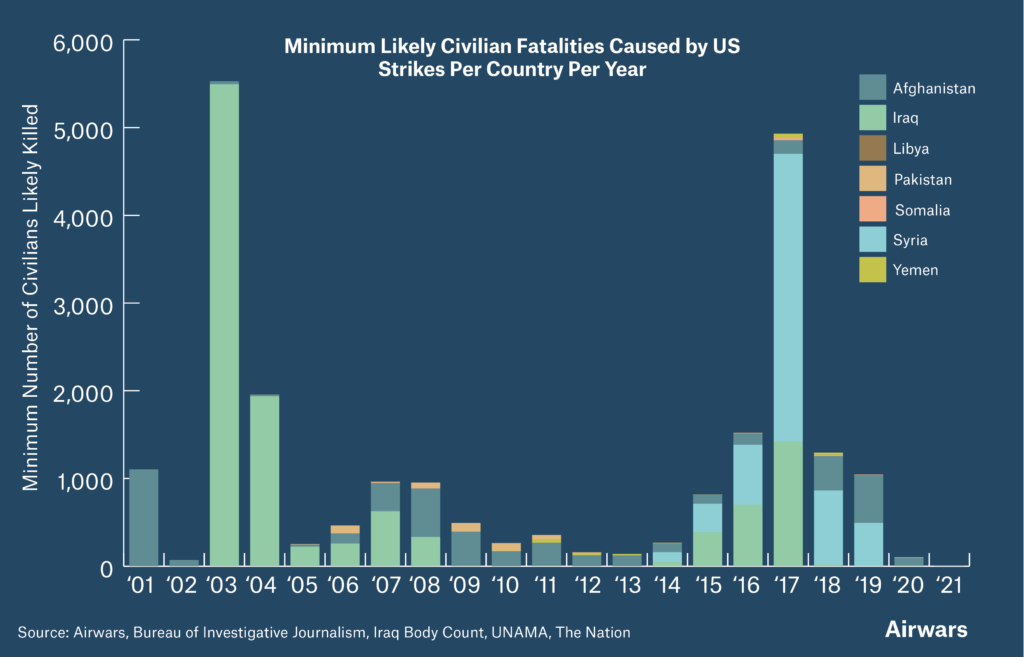

During 2020 the UN concluded, more than 3,000 Afghan civilians were killed in ongoing fighting between the Taliban and the then-Afghan government, supported by international forces. According to UNAMA, 341 civilians were killed that year by airstrikes – of which it blamed 89 deaths on international forces.

Yet UNAMA’s 2020 annual report said that after the February 29th agreement between the US and Taliban “the international military significantly reduced its aerial operations, with almost no such incidents causing civilian casualties for the remainder of 2020.”

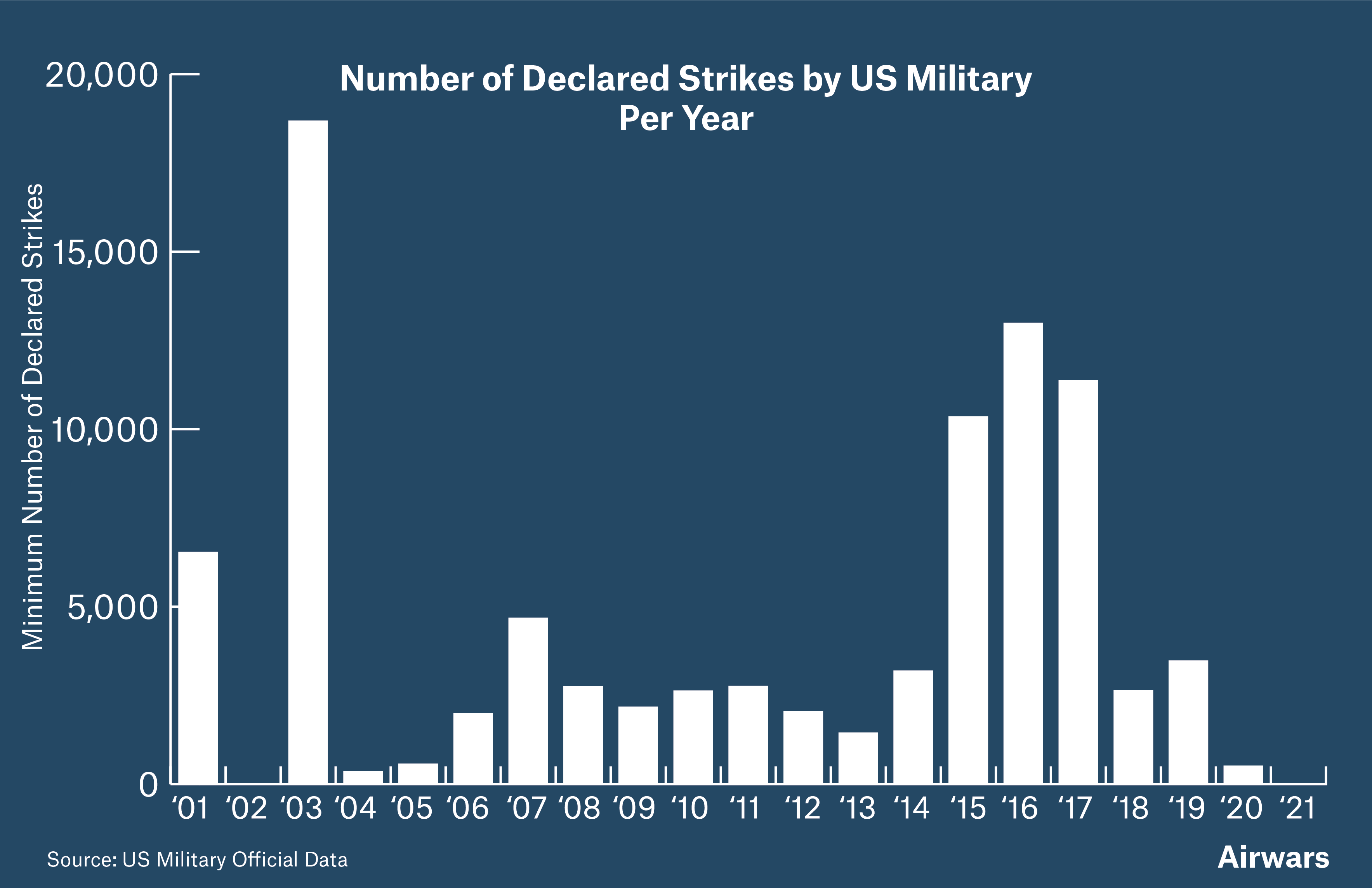

UN officials later told Airwars during a briefing that they believed Afghan Air Force strikes were now likely responsible for almost all civilian deaths from airstrikes. The release of the previously-classified data from AFCENT radically changes that picture. Between March and December 2020, Trump’s last full months in office, the US in fact carried out 413 airstrikes – as many as during all of 2015 for example.

For the first half of 2021, UNAMA also made similar assumptions about low numbers of US and international strikes, noting that “compared with the first half of 2020, the total number of civilians killed and injured in airstrikes increased by 33 per cent. Civilian casualties from Afghan Air Force airstrikes more than doubled as international military forces conducted far fewer airstrikes.”

In fact, we now know, more than 370 ‘international’ strikes were carried out in 2021, which between them dropped more than 800 munitions.

UNAMA did not immediately respond to questions on whether the UN would now be reviewing its recent findings, following the release of the AFCENT data.

Biden under scrutiny

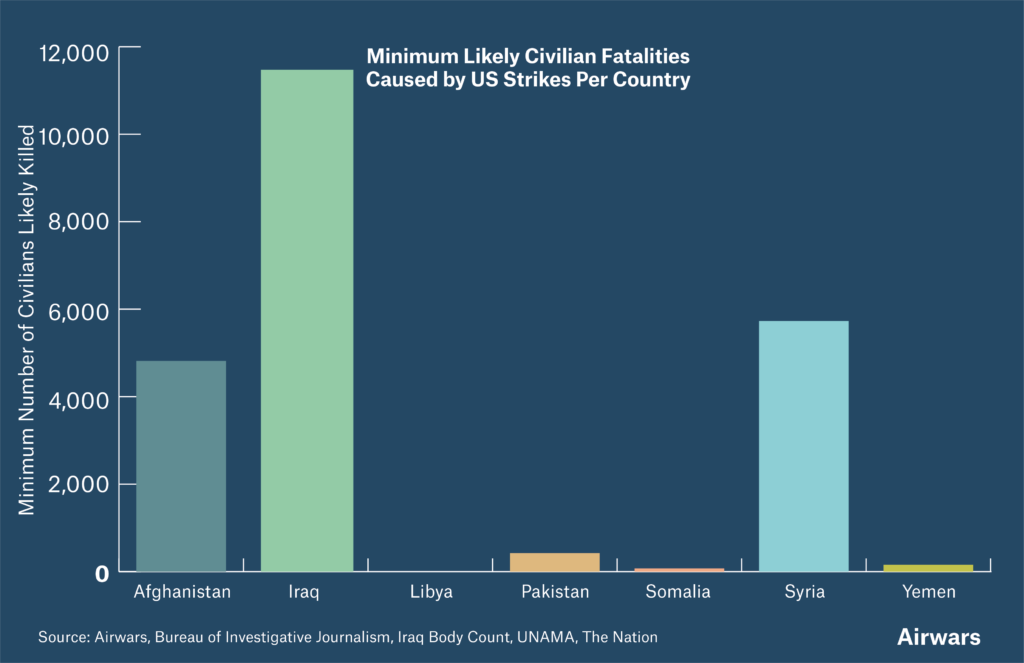

Revelations of hundreds of previously secret US airstrikes in Afghanistan during Joe Biden’s first months in office indicate that while US actions were at record lows in other theatres such as Iraq and Somalia, the intensity of the 20-year war in Afghanistan continued to the very end.

More than five times more US strikes were conducted in Afghanistan from January to August 2021 than have been declared in all other US theatres combined across the whole year, Airwars analysis shows.

“Airwars has been cautioning for some time that recent airstrike numbers for Afghanistan – if revealed – might show far more US military activity under Joe Biden than many had assumed,” said Airwars director Chris Woods. “This newly released data – which should never have been classified in the first place – points to the urgent need for reevaluation of recent US actions in Afghanistan, including likely civilian casualties.”

The Afghanistan data stops abruptly in August 2021. Announcing the release of the previously secret strike and munition numbers to the Pentagon press corps late on Friday afternoon, chief DoD spokesman John Kirby told reporters: “There have been no airstrikes in Afghanistan since the withdrawal is complete.”