There has been much speculation in recent weeks about what President Biden’s first year in office shows us about his foreign policy – and in particular whether he is ending 20 years of America’s so-called ‘forever wars’.

As 2021 nears its end, Airwars reached out to US combatant commands to request strike data for conflicts. Coupled with the long-delayed release of crucial strike data from Afghanistan, Airwars can assess for the first time what the ‘war on terror’ looks like under Joe Biden.

The biggest take-home is that Biden has significantly decreased US military action across the globe.

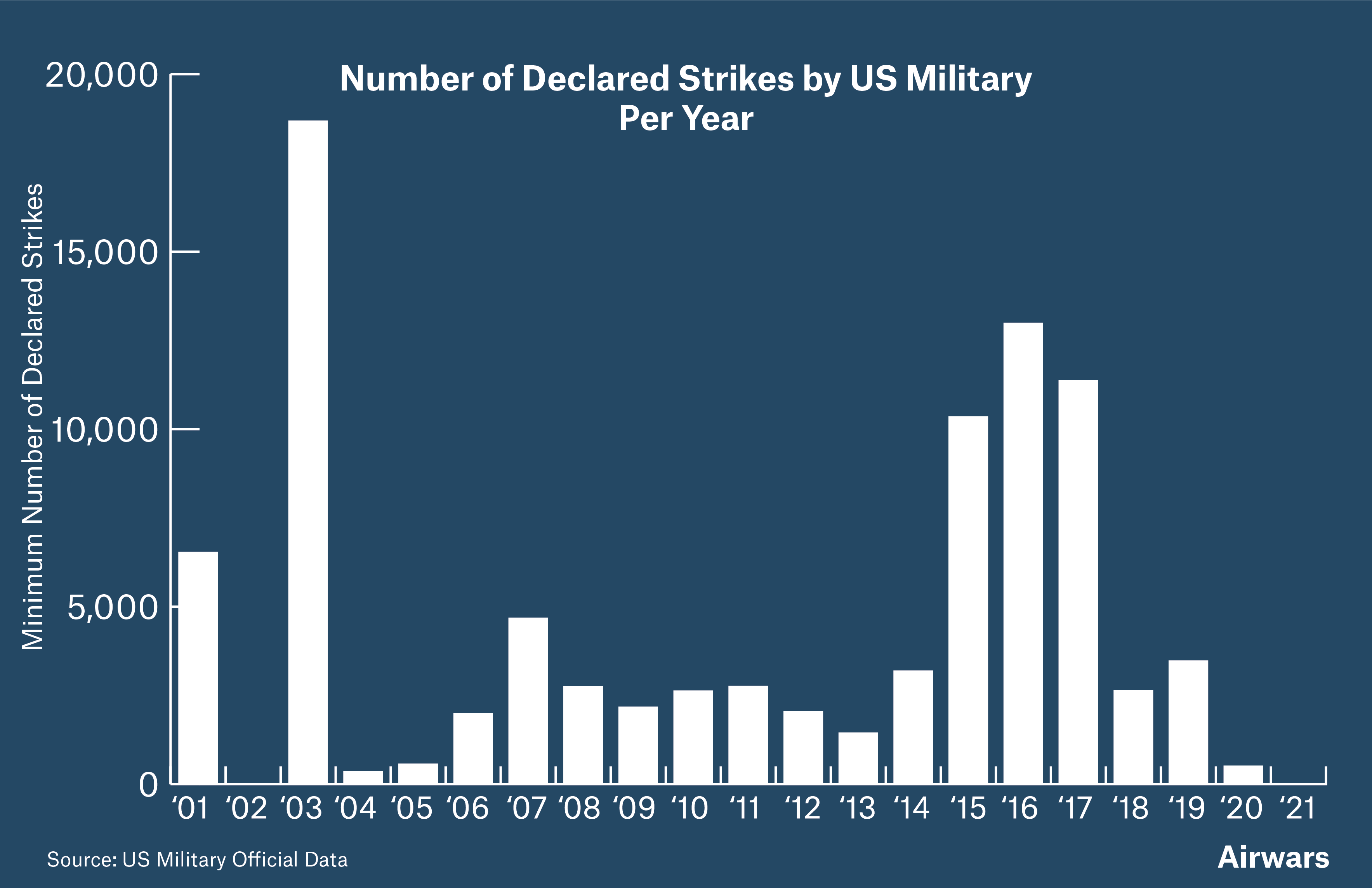

Overall, declared US strikes have fallen by 54% globally during 2021

In total, declared US strikes across all five active US conflict zones – Afghanistan, Iraq, Somalia, Syria and Yemen – fell from 951 actions in 2020, to 439 by mid December 2021, a decrease of 54 percent. This is by far the lowest declared annual US strike number since at least 2004, and reflects a broader trend of declining US actions in recent years.

During 2021, the overwhelming majority of US strikes (372) took place in Afghanistan prior to withdrawal on August 31st. In fact, the United States carried out more than five times as many strikes in Afghanistan this year than in all other active US conflict zones combined.

If you were to remove Afghanistan from the data, the United States has declared just 67 strikes across the globe so far in 2021.

Afghanistan dominated US military actions during 2021

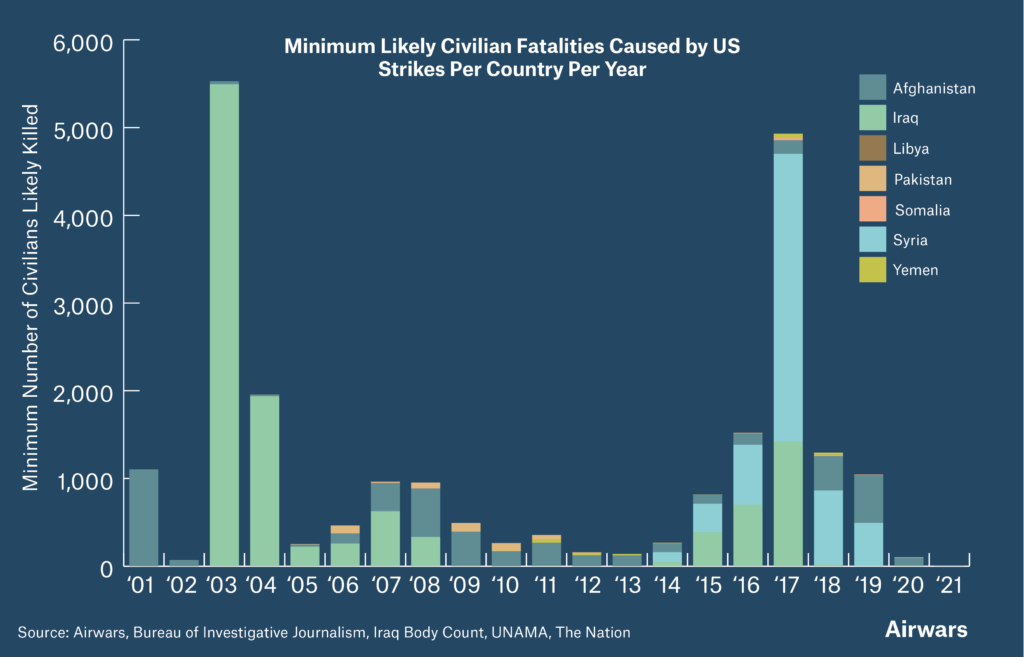

Civilian casualties also down

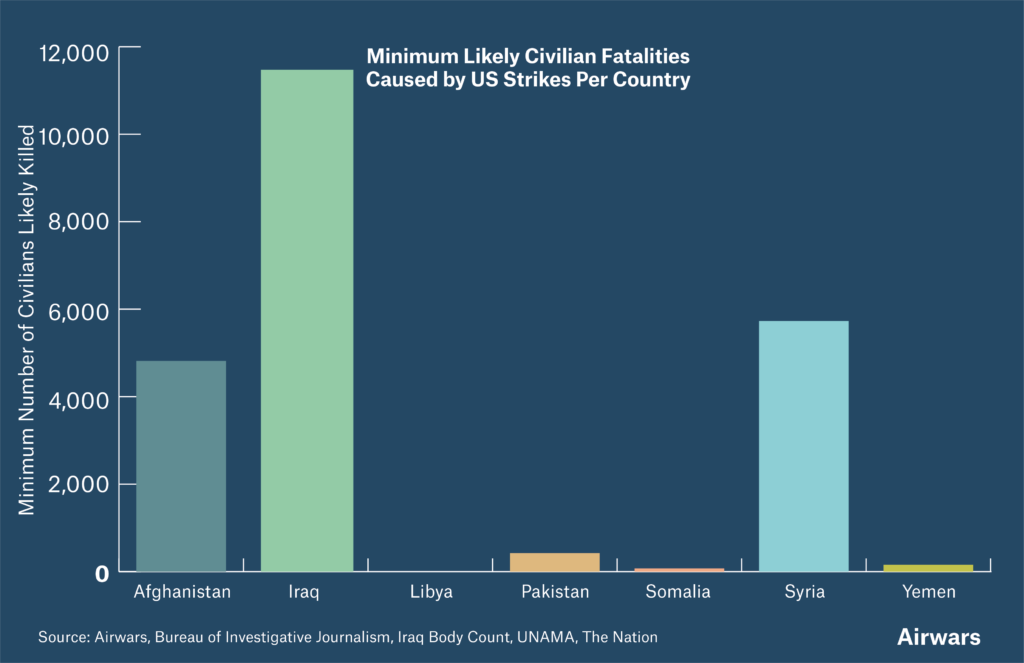

This trend is also reflected in far lower numbers of civilians allegedly killed by US strikes. During 2021, there were no credible local allegations of civilians likely killed by US strikes in Iraq, Libya, Pakistan or Yemen.

However, at least 11 civilians were likely killed by US actions in Syria. In Afghanistan at least 10 civilians were confirmed killed by US actions. That latter figure is almost certainly higher, since we now know the US dropped more than 800 munitions on Taliban and Islamic State fighters during the year. At least some of those strikes were in urban areas where civilians are particularly at risk. However exact estimates remain elusive, due to ongoing confusion between US strikes and those carried out by Afghan security forces up to August.

In Somalia one civilian was locally reported killed by US strikes, though this occurred before Biden assumed office on January 20th.

Biden is partly continuing a trend seen in recent years – the number of strikes has largely fallen since 2016 when the war with the so-called Islamic State reached its apex. Below, we provide breakdowns of both US and allied airstrikes and locally reported civilian casualties – as well as emerging trends – for each individual conflict.

Over the length of the ‘War on Terror’, the invasion of Iraq in 2003 still marks the highest number of declared US strikes.

Afghanistan

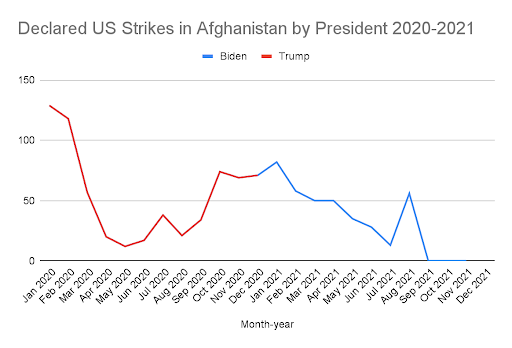

On December 17th 2021, Biden’s administration finally released strike data for the final two years of the Afghanistan war. Such monthly releases were standard practice for nearly two decades but were stopped in March 2020, with the Trump administration arguing that their ongoing release could jeopardise peace talks with the Taliban. The Biden administration then chose to continue with that secrecy.

Now we can see why. The new releases show that despite a ‘peace’ agreement with the Taliban signed on February 29th 2020, under which the US was expected to withdraw in 14 months, the Pentagon continued its aggressive aerial campaigns in Afghanistan. Between March and December 2020, more than 400 previously undeclared strikes took place under Trump, while there were at least 300 US strikes in Afghanistan under Biden until August.

In total, almost 800 previously secret recent US airstrikes in Afghanistan during the Trump and Biden administrations have now been declared.

While Airwars does not track allegations of civilian harm in Afghanistan, the United Nations Assistance Mission to Afghanistan (UNAMA) has done so for more than a decade. Yet the decision by the Pentagon to stop publishing strike data in early 2020 may have led the UN to significantly underestimate casualties from US actions.

In its report detailing civilian casualties in Afghanistan from January to June 2021, UNAMA found that 146 civilians had been killed and 243 injured in airstrikes. Yet it seemed to assume these were all carried out by US-backed Afghan military forces, instead of the US.

“UNAMA…did not verify any airstrike by international military forces that resulted in civilian casualties during the first six months of 2021,” the report asserted. Such assessments will likely now require a fresh review, in the wake of recent US strike data releases.

We do know for certain that ten civilians were killed by US actions after that six-month period, on August 29th this year in Kabul – in the final US drone strike of a 20-year war. The US initially claimed this was a “righteous strike” on an Islamic State terrorist. However investigative journalists quickly showed the victims were in fact an aid worker and nine members of his young family, forcing the military to admit an error. Despite this, it recently concluded no disciplinary measures against personnel were necessary.

After the ignominious US withdrawal on August 31, US strikes have stopped. While at the time Biden discussed the possibility of continuing “over the horizon” airstrikes from a nearby country, this has not yet happened.

“The skies over Afghanistan are free of US war planes for the first time in two decades. A whole generation grew up under their contrails, nobody looks at the sky without checking for them,” Graeme Smith of the International Crisis Group told Airwars. “Their absence heralds the start of a new era, even if it’s not yet clear what that new chapter will bring.”

Iraq and Syria

During 2020, the number of air and artillery strikes conducted by the US-led Coalition against the Islamic State – Operation Inherent Resolve – has continued to fall, alongside an ongoing reduction in civilian harm allegations.

OIR declared 201 air and artillery strikes in Iraq and Syria in 2020, and only 58 strikes by early December 2021. This represents a reduction of around 70 percent in one year, and a 99 percent reduction in declared strikes between 2017 and 2021.

In Iraq, Airwars has tracked no local allegations of civilian harm from US led actions during 2021, down from an estimated five civilian fatalities in 2020. At the height of the Coalition’s war against ISIS in 2017, Airwars had tracked a minimum of 1,423 civilian fatalities.

In Syria, however, civilian harm allegations from Coalition actions actually increased this year, up from a minimum of one death in 2020 to at least eleven likely civilian fatalities in 2021. This does still represent a low figure compared to recent history: in 2019, Airwars had identified a minimum of 490 civilians likely killed by the Coalition, a reduction of 98 percent to this year.

Since 2019, Afghanistan has replaced Iraq and Syria as the primary focus of US military actions.

One key concern in Syria is that most recently reported civilian deaths have resulted not from declared US airstrikes, but from joint ground operations with Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), often supported by US attack helicopters.

These include a raid on the town of Thiban in Deir Ezzor, carried out by the SDF with the support of the US-led Coalition at dawn on July 16th 2021. Eyewitnesses reported that a “force consisting of several cars raided civilian homes, without warning, accompanied by indiscriminate shooting between the houses with the aim of terrorising the ‘wanted’”. Two civilians, a father and son, were killed in the raid, reportedly shot outside their home.

Separately, on the morning of December 3rd 2021, a declared US drone strike killed at least one man and injured at least six civilians, including up to four children from the same family. Multiple sources reported that the drone targeted a motorcycle but also hit a passing car that the Qasoum family were traveling in. Ahmed Qasoum, who was driving, described the incident; “the motorcycle was going in front of me and I decided to pass it, when I got parallel to it, I felt a lot of pressure pushing the car to the left of the road….It was horrible.” His ten-year-old son had a fractured skull, while his 15-year-old daughter sustained a serious shrapnel injury to her head.

On December 6th, Pentagon Press Secretary John Kirby said the strike had targeted an Al-Qaeda linked militant but “the initial review of the strike did indicate the potential for possible civilian casualties.”

+18 | "دوبلت الموتور إجت طيارة استطلاع ضربتني"يستمعون إلى الموسيقا وفجأة..مشهد مرعب للحظة استهداف عائلة في ريف #إدلبخاص #تلفزيون_سوريا@syriastream pic.twitter.com/ao0hy4stb1

— تلفزيون سوريا (@syr_television) December 5, 2021

A dashboard camera captures the moment a US strike also hits a passing civilian vehicle.

Libya, Pakistan, Somalia and Yemen

Under Donald Trump, there had been a record rise both in declared US airstrikes in Somalia, and in locally reported civilian deaths and injuries – with the last likely death from a US action tracked by Airwars on the final day of Trump’s presidency.

Since then, Airwars has tracked no locally reported civilian deaths in Somalia under Biden. For the entire year, AFRICOM has declared nine strikes so far, four of which occurred under Biden. When he came to power, his administration implemented a six-month moratorium on strikes, multiple sources said. This meant that both AFRICOM and even the CIA had to have White House permission before carrying out strikes in either Somalia or Yemen.

On July 20th 2021, the day the moratorium ended, AFRICOM declared the first Somali strike of the Biden era – targeting the Al-Shabaab Islamist group. Multiple militants were reported killed, though no civilians were among them. A small number of additional strikes against Al-Shabaab occurred in the weeks afterwards, the most recent of which was on August 24th. Since then, there have been no declared strikes.

In Yemen, where the US has carried out periodic strikes against alleged Al-Qaeda affiliates since 2009, there have so far been no reliable reports of US strikes under Biden. In August, Al-Qaeda itself claimed two of its fighters had been killed in a US action, though there were no details on the date or location of this event.

Responding to an email query from Airwars on November 18th, the US military denied carrying out any recent attacks, noting that “CENTCOM conducted its last counterterror strike in Yemen on June 24, 2019. CENTCOM has not conducted any new counterterror strikes in Yemen since.”

However, in a more ambivalent statement to Airwars on December 16th, CENTCOM spokesperson Bill Urban noted only that “I am not aware of any strikes in Yemen in 2021.” Airwars is seeking further clarity, particularly since it is known that the CIA carried out several airstrikes on Al Qaeda in Yemen during 2020.

In both Libya and Pakistan, long running US counter terrorism campaigns now appear to be over. The last locally claimed CIA strike in Pakistan was in July 2018 under President Trump, while in Libya, the last likely US strike was in October 2019.

A crucial year ahead

Based on official US military data, it is clear that Joe Biden is building on a trend seen in the latter years of Donald Trump’s presidency, further decreasing the scope and scale of the ‘forever wars.’

In Iraq and Syria, US forces appear to be transitioning away from carrying out active strikes in favour of supporting allied groups – although Special Forces ground actions continue in Syria, sometimes with associated civilian harm. The war in Afghanistan is now over, and it seems the long-running US campaigns in Pakistan and Libya have drawn to permanent halts. US airstrikes in Somalia and Yemen have all but stopped for now.

Still unknown is the likely framework for US military actions moving forward. In early 2021, Biden commissioned a major review of US counter terrorism policy. Led by National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan, the results are expected to be announced in the coming months. This will likely give us a far clearer idea how Biden believes the US should fight both ongoing wars and future ones.

Is 2022 the year Biden rescinds the AUMF? (Official White House Photo by Adam Schultz)

And then there is amending – or even repealing – the 2001 Authorization for the Use of Military Force (AUMF). That law, passed by Congress in the wake of 9/11, essentially granted the US President the right to conduct strikes anywhere in the world in the context of the ‘war on terror.’ Initially designed for use against Al-Qaeda, it has been employed against an ever widening pool of US enemies.

The future of the 2001 AUMF is once again likely to be debated by Congress in 2022. While unlikely to be repealed, it could possibly be significantly amended, Brian Finucane, senior advisor for the US programme at International Crisis Group, told Airwars.

“That would entail at a minimum specifying who the United States can hit – explicitly identifying the enemy. Secondly identifying where it should be used – geographical limits. And thirdly giving a sunset clause,” he said. “As it is now that AUMF is basically a blank cheque to be used by different administrations.”