Following the 2011 toppling of dictator Muammar Gaddafi in a NATO-backed uprising, Libya has seen significant upheaval and civil conflict.

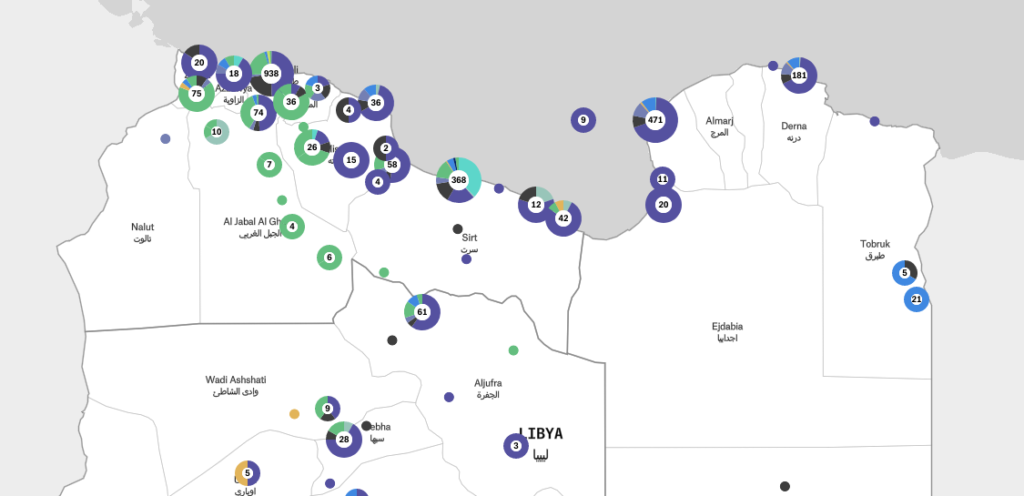

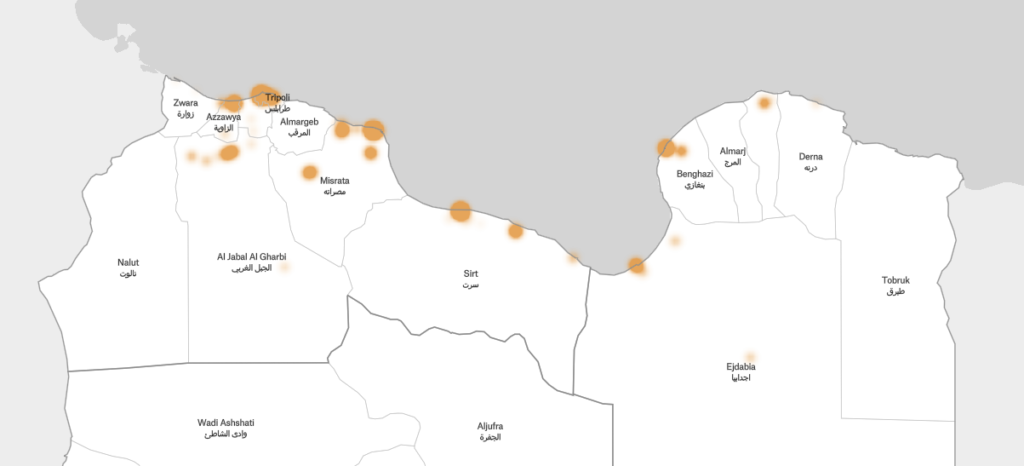

Airwars has documented allegations of civilian harm caused by all actors in Libya since 2011, while also conducting a number of major investigations into the conflict.

Conflicts monitored involving Libya