Beginning in 2014, the United Nations Monitoring Mission in Ukraine has been tasked with recording civilian casualties in that country. Until February 24th, the conflict was relatively low intensity. Russia’s invasion and subsequent attacks on communities across a swathe of Ukraine saw a huge rise in reported civilian deaths, which the UN Mission continues to track.

With the Ukraine Government ceasing its own public national estimates of civilian harm just four days into the war, the UN’s own daily cumulative tallies have become the sole official source for national casualty estimates. By early April, the UN had recorded at least 1,500 civilian deaths – while also publicly acknowledging that was likely a significant undercount.

Uladzimir Shcherbau joined the UN Monitoring Mission in Ukraine back in 2014, and today leads its civilian casualty monitoring unit. Almost all of the team remains in Ukraine – some close to the front lines – and all of them doing extremely challenging work.

In this extended interview with Airwars director Chris Woods conducted on April 1st, Uladzimir discusses among other topics the challenges of UN casualty counting following Russia’s invasion; how the Mission plans to address its own low estimates of harm; and the horrors of Russia’s onslaught on the Ukrainian city of Mariupol.

Some key points from this interview were also summarised in this article for The Independent: UN estimate of civilian casualties in Ukraine set to increase, official says

What’s the purpose of the UN gathering civilian casualty data?

Why do we do it? It’s not just about gathering data. We have three or four major objectives, to which the information we collect should serve. The first is decision making by military and political actors – ideally to facilitate the cessation of hostilities, and definitely compliance with International Humanitarian Law (IHL). When we see the patterns of IHL violations – it is not our major objective, and very often in such contexts it is very difficult to establish whether the civilian was the result of IHL incompliance or in the worst cases of war crimes – but surely some of our findings would inform the deeper investigations and we do work deeply in some incidents – as we did for the period 2014-2021.

Ideally we go really deep into each single civilian killed, we establish as an ideal minimum the date of the incident, the status of the victim killed or injured, then if possible the name of the victim, then the age, definitely sex, place where it happened – as precisely as possible, if not geographic coordinates – then ideally the settlement or a specific area. Then control over the area – which party controlled the area – and then the weapon and the situation in which the casualty occurred. And we only record civilian casualties, not military casualties. When we have the slightest hesitation that a person might have been Directly Participating in Hostilities, we don’t include them in our figures.

In the current context I would put it like this. Because the amount of material we have to process is enormous and the time constraints are also enormous, we cannot go too deeply into each individual incident. I would describe this as ‘temporary superficiality’.

How is UN civilian harm monitoring presently structured in Ukraine? How big is the team? And are you still able to operate?

Most of the team is located in Ukraine in various places – not in the places where the hostilities are going on but in other places, sometimes nearby, which allows us to reach out to Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs), to people who evacuated from the conflict-torn areas, and to get access to first hand witnesses and victims. And we are still physically present in Donetsk and Luhansk, which Russian-affiliated armed groups control. We have been in those areas since 2014 and 2017 respectively, and we are still physically present in Donetsk, with certain restrictions on our operations there, and also those stemming from the security situation.

We have 37 human rights officers and several interns who have been working on monitoring and to a certain extent everyone is engaged in civilian casualty recording as well. But dedicated work on civilian harm is done by a small unit which I am in charge of.

How have you been able to continue this critical work following Russia’s invasion in February?

We apply the global [UN] guidance on how to record civilian casualties and it is fairly simple – we collect information from the best sources we can, preferably at least three independent sources and then based on the body of information we collected, we assess the sources based on their credibility and reliability. We also follow the patterns of violations which also allow us to assess, to verify, and to corroborate – so we collect a lot of information about the hostilities in general which also allow us to better understand the specific incident.

Basically we have three or four types of information. Definitely we take stock of all available official information – local authorities, national authorities, regional authorities, medical institutions, emergency services, police, very often military experts and some others – any state official or a person working in a facility who has some information on casualties. We take stock of all the information they provide.

We often reach out with requests for specific information but in the current context we see that the state agencies are overwhelmed with the numerous challenges, and they don’t have time to respond to our questions. But they do still report on civilian casualties – for example giving totals per region. Not only figures but we also receive a lot of descriptive narrative for specific incidents.

And when someone says ‘ok there was an incident in settlement X and there were a lot of civilian casualties’, in our records, as you can understand, it would be recorded as zero casualties unless we can understand the specific incident. But we take stock of all this information, it is extremely valuable, and we do analyse it systematically. So we have a mosaic of all these official reports.

Within weeks we saw which of these authorities provide consistently reliable information, and those which unfortunately are giving extremely vague information based on plausible assumptions and these assumptions do not get additional credibility simply because they are made by an official. They are definitely free to make any assumptions or judgements based on intuitive thinking but we clearly see in some cases it is not factually based.

The second source for our team is publicly available information on these incidents. In that regard the situation in Ukraine is extremely transparent – available through publicly available sources – Telegram, Facebook, Internet. Roughly speaking, we are talking about a lot of video footage, a lot of photos, and a lot of narrative reports. The number of channels in which people report is enormous. We do systematically follow as much as we can on these channels – very often it’s a local channel for a specific village or something. If you think about Mariupol – which is besieged and the situation is really bad and information is imprecise – people are reporting per quarter what happened in a specific house or area. We use all this information for our analysis and we collect it systematically.

Then there is our outreach to informed individuals. We had, for example, developed a broad network of contacts prior to the present high intensity conflict. All our offices and field presence were mostly in the east of Ukraine. And we are reaching out to these people to get information that is extremely valuable. I will give you just one example – we had a trusted partner NGO which had worked a lot in the east and there were for instance two towns in the Lugansk region which were well known to those who follow Ukrainian events. Shastiya and Staniska-Uganska. And there were hostilities from the very beginning there, and the NGO reached out to medical professionals working in the area to get very detailed medical records about casualties. So we use this network of contacts. They proactively provide us with some information but we also request them to provide us with some information.

And finally, we also publicly announced that we are interested in receiving information about civilian casualties – and so people send us information through Telegram, Facebook and by email. We cannot cover it (fully) as we don’t have the capacity but we increasingly interview IDPs from the conflict affected areas – and also receive first hand accounts of individual incidents in which civilians were killed or injured.

So altogether we collect this information systematically – not only what happened yesterday but about what happened three weeks ago. If there is a (new) photo of a grave with the names on it from the town recently retaken by Ukrainian forces we go back to the records and check the names. All of that together.

Then we analyse this information, and once we come to conclusions that we have reasonable grounds to believe it happened, then it goes to our figures – the case is corroborated. It doesn’t mean we have all the information – maybe we don’t know the sex of the victims or something – but we still believed it happened and it goes into our figures.

Those cases which have not yet reached this stage we call ‘yellow cases’, which are still pending further verification and corroboration and we have many such cases which are in the process of corroboration. Some of them could stay marked as pending corroboration for months, if not years, some of them could be corroborated tomorrow if new information comes. So we are always reassessing such cases and seeing if anything is new. It’s like a mosaic – sometimes you get new information, and the puzzle comes together and a case becomes corroborated. This is how we do it.

The volume of casework you are dealing with must be staggering. What adjustments have you had to make?

It is not a dramatic shift compared to what we did before. We did roughly the same from 2014-2021 – the only thing was the intensity of hostilities was much lower starting from 2015 and we then had the luxury (of) following each individual incident really deeply – going to the place, speaking to the people, getting forensic records etc

And today? Let’s say there is a report of an airstrike in Kiev with reported civilian casualties. Then we take note of this report. Then the city council says it was a centre for the distribution of humanitarian aid and 20 people have been killed on the spot – without specifying whether they were civilians or militants. That’s ok but it is not enough for us. Then video footage becomes available, and in that footage we see four bodies of people who appear to be civilians, some of them women, some can’t be identified but they don’t look like military or paramilitary. And there are also some people in the local chat groups saying a ‘horrible thing happened in this street and I was there and it was a Hell.’

So once again having analysed all this information we believe we have reasonable grounds to believe that the incident happened, and the overall context that the city was under fire, the military actors reported that incident, the General Staff is reporting that there was heavy shelling of this city, we have records from previous days that this area is being targeted, probably we will get some satellite imagery showing the neighbourhood affected. We can reach out to our partner in that area and ask if there was something and they might say “I don’t know what happened, I was 5km from that place, but there was something horrible.” And then, we say we saw five bodies. We don’t write ‘many’, we don’t write 20, we write five people were killed in that incident – including perhaps one man and two women – on that day.

This is roughly how we arrive at a conclusion, but once again it depends on the situation

From our experience usually reports of civilian casualties are not fake – sometimes there could be deliberate attempts to present certain incidents, to portray the other side as a perpetrator. But it is so easy to debunk such fakes so I don’t believe it happens often. Mostly reports are accurate, there could be some sort of natural imprecision or mistakes – very often when you receive a report about a civilian and the name – how the family name is spelled may not be found in the registration of population. But then you realise this family name is accurate – it was just a (spelling) mistake in the report – and you realise it’s indirect evidence that the report is authentic, because most likely the report was made on the phone and the person who wrote down the family name just didn’t hear it properly.

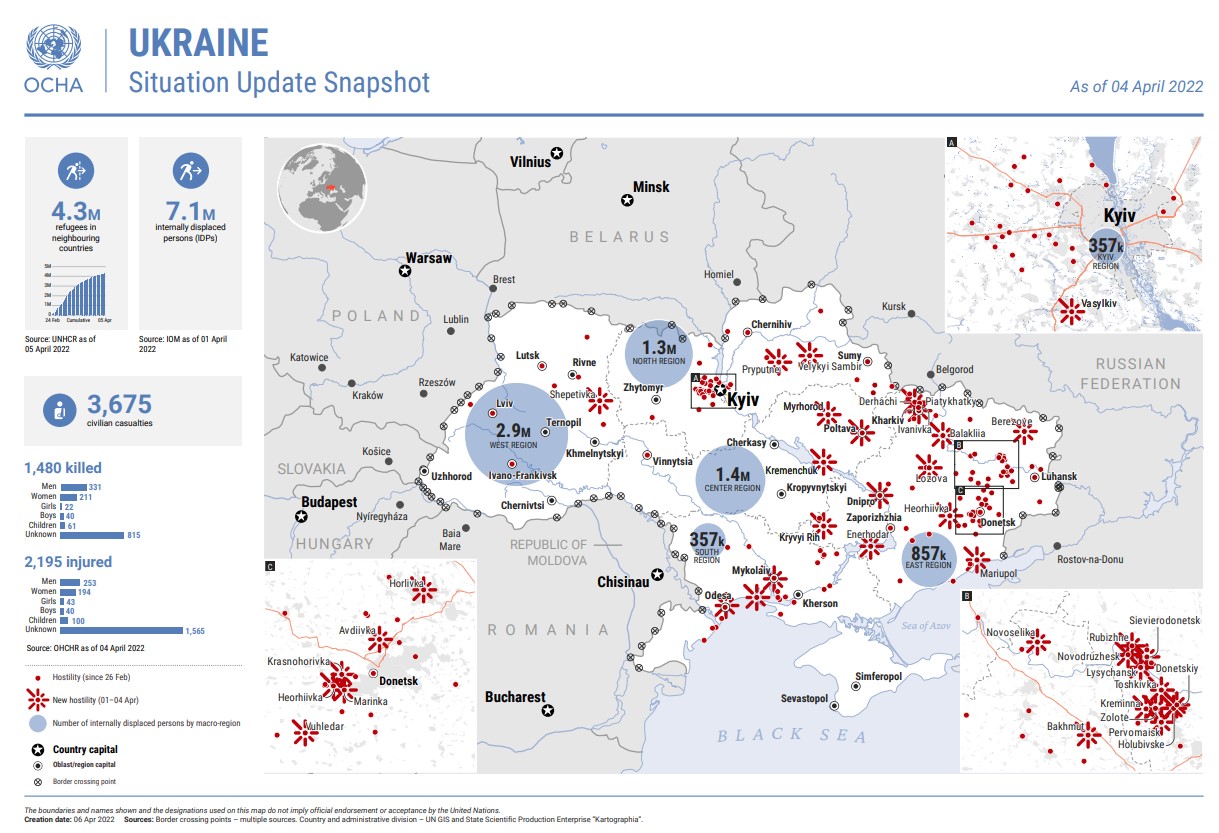

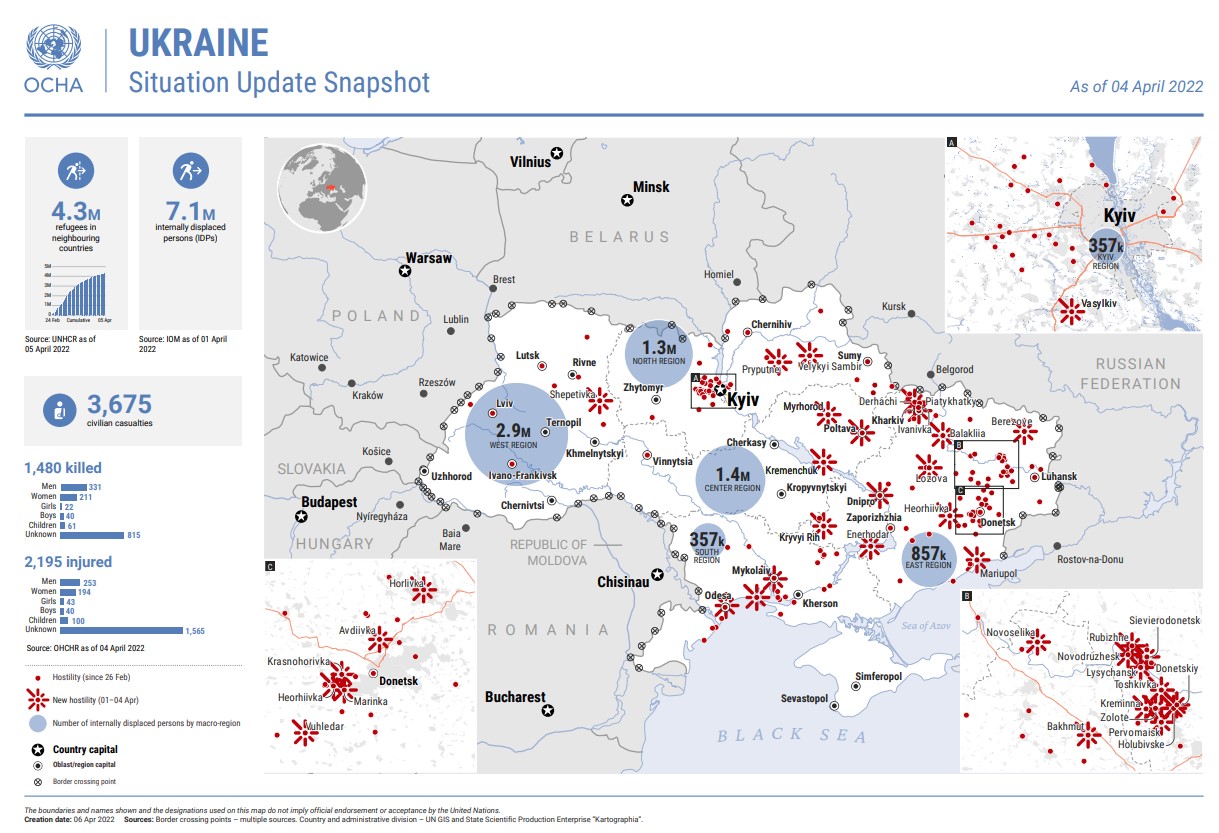

UNOCHA conflict map of Ukraine for April 4th 2022.

Civilians have been urged by some to take up arms during the present conflict and to Directly Participate in Hostilities. How does that affect categorisations for you, when you’re making a determination of civilian harm?

Methodologically it is fairly simple – civilians are those who don’t take direct participation in hostilities. You don’t have to be a member of the armed forces or paramilitary formations to be counted as not a civilian – it could be purely a civilian who took his or her arms to fight. As soon as you directly participate in hostilities you are not a civilian any more. If such people are killed or injured we exclude them from the UN count.

There could be some marginal cases where there could be questions and you cannot be 100% sure how to classify this person as a civilian or not, but statistically these cases are extremely insignificant and for methodological purity we exclude such debatable questions from civilian casualties.

And we have a fairly clear definition. If there is a policeman who is performing regular police functions in the conflict zone and is killed or injured by hostilities and he or she is not taking part in hostilities – just patrolling the area in the conflict zone when he or she was killed or injured by shelling – we consider them a civilian casualty. If a police officer is present in a conflict zone to maintain law and order as part of enhanced police deployment, and basically also controlling the area recently taken under control, or doing some sort of paramilitary function, he or she is not a civilian any more.

We even excluded cases which could be very marginal – for instance if there is a military unit which is stationed in a certain location and there is a civilian who regularly brings some food to this unit – maybe paid or not, but somehow helps them to sustain. It is easy to argue that this person is not taking part in hostilities but we exclude such cases.

Statistically such cases are marginal but we exclude even very marginal cases so probably decreasing the toll a little. But statistically, it’s pretty clear whether a person participates in hostilities or not.

What is the situation for civilian harm in breakaway and Russian-occupied areas? How able are you to capture that?

For us it doesn’t make any difference – we are covering the entire territory of Ukraine within its internationally recognised borders, and we do follow all the reports and do our best to corroborate all civilian casualties wherever they happen. And we do it in regard to territory controlled by the Russian-affiliated armed groups or the territory which is currently under the control of the Russian armed forces. We have certain difficulties in getting the information but it is roughly the same as getting the information from government-controlled territories. We also do breakdowns for Donetsk and Luhansk regions, for government controlled territory, and for territory controlled by Russian affiliated armed groups.

We haven’t yet published figures from the places which had been controlled by Russian Armed Forces – say from the Kharkiv or Chernihiv or Kherson regions. But we are also coming with those figures fairly soon. So once again, we do take stock of all civilian casualties, including in the territory which is presently outside of Ukrainian government control.

In your own daily press releases you are very clear that the true casualty figure is likely much higher. How wide a gulf might there be between UN estimates and the actual civilian toll?

I wish we had this interview in the next week or two. We are working right now on a realistic estimate of the actual death toll of the conflict. We have a big mass of information which allows us to triangulate or somehow approximate the actual death toll. I wouldn’t give you specific figures right now because it is extremely sensitive and we are under enormous pressure because we are criticised heavily – they are saying ‘your figures are irrelevant. It’s nice that you give these at least figures but they are irrelevant because the real death toll is higher’ as we ourselves point out in our daily updates.

But we have data, we have information, we have a really solid methodology – it is not pure maths, it is looking at patterns, correlations, available information per region and per type of casualties to come (up) with this realistic estimate and once again we will soon come up with an estimate fairly soon.

We believe it would be pretty accurate. The figure would be fairly reflective of the actual scale – it will be also conservative, not to go too broad, but we believe it will be fairly close to the actual death toll. All in all we would come with a rather accurate total and the gaps within the estimate of actual total and real total would not be so big. We believe we will give a gist of what the scale is – of the true scale we believe of the casualties – especially of those killed.

Low UN estimates have been cited to downplay deadly effects of Russia’s invasion.

The city of Mariupol reports more than 5,000 civilian deaths so far. What do you make of that estimate?

When we speak about Mariupol, it is definitely the deadliest place in Ukraine currently. We have been in touch with city authorities, with the city council – we do follow the data they provided and we requested additional data and they committed to providing us as much as they can, but they have been working in extremely challenging conditions as you can understand. Even so, they estimate 5,000 civilian deaths from just three weeks of hostilities in March.

Our own UN estimate should come hopefully fairly soon as we managed to collect information about Mariupol, we analysed all the narrative reports, official figures and official reports from medical (authorities) – sometimes fragmented but also some information which allows us to see the pattern from emergency services and video footage. We also do satellite imagery analysis – not only on damage. So we hope to come with a rather realistic, from our perspective, estimate.

The amount of conflict death is enormous, but also surely people kept dying in besieged Mariupol because of regular mortality, many people died as indirect casualties because of stress and the collapse of medical aid. And reportedly many suicides have occured in Mariupol. We have had several reports saying that the suicide rates increased, that’s for sure.

So it needs also to be factored in that all these people died during this one month of hostilities – though the UN Mission ourselves strive to single out the civilians who have been directly killed by hostilities, and we will come up with our estimate pretty soon.

Given this scale of harm, how long might it be before the UN has a comprehensive tally of civilian deaths at Mariupol?

When will the world know for sure when hostilities are over the exact number of civilians who have been killed in Mariupol from day one until the last day of hostilities? That will surely take time. It will take time to recover all the bodies, to identify them, and because there was a mass displacement for example, some people who were evacuated from Mariupol, some injured people who could have died in medical facilities outside of Mariupol. So the ultimate accurate figure won’t arrive quickly.

We have credible reports that there are still many bodies in the debris. Some bodies are unattended in the apartments – no one was (able) to take care of the bodies. Many bodies have been buried in improvised graves – they also need to be exhumed and reburied individually and with proper decency. That will also be an enormous challenge for the city. We have seen a lot of footage of graves in peoples’ yards, which is appalling.

So we will analyse all the information and try to come up with our own estimate but surely for the future that will be a horrible and heartbreaking task – not only to count people, but to ensure decent treatment of those who perished. And then once again to work for reparations and bring the perpetrators to justice. The preservation of evidence – which is what dead bodies are – will be extremely essential.

Radio Svoboda’s recent drone footage showing the devastation of Mariupol.