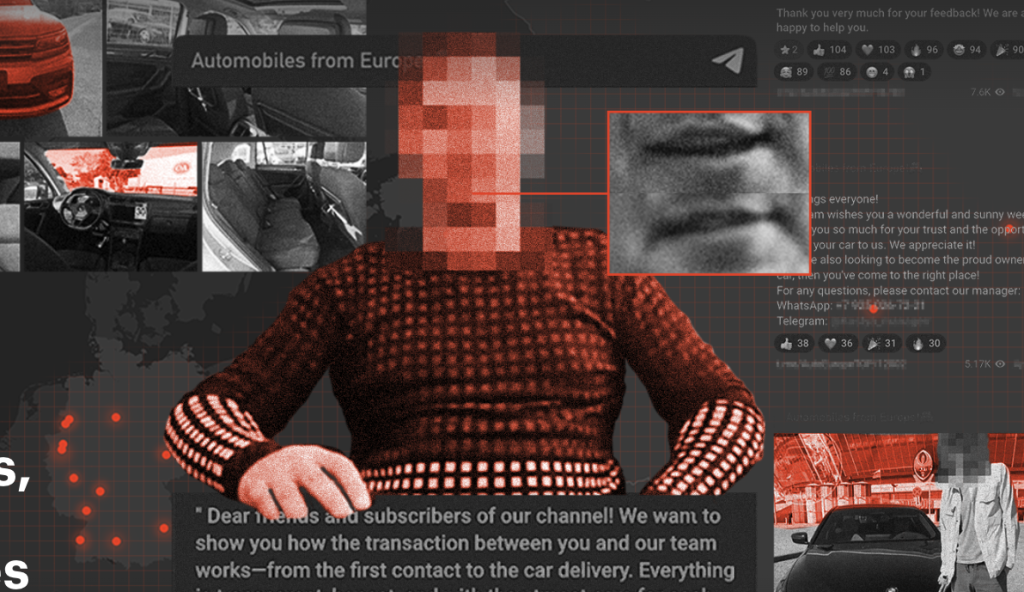

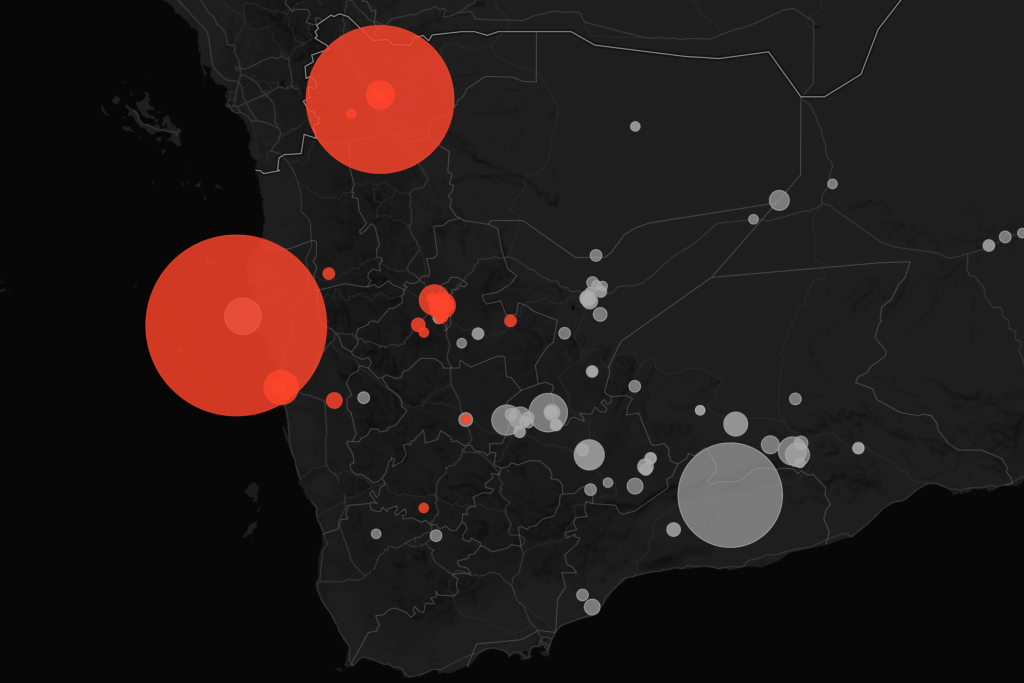

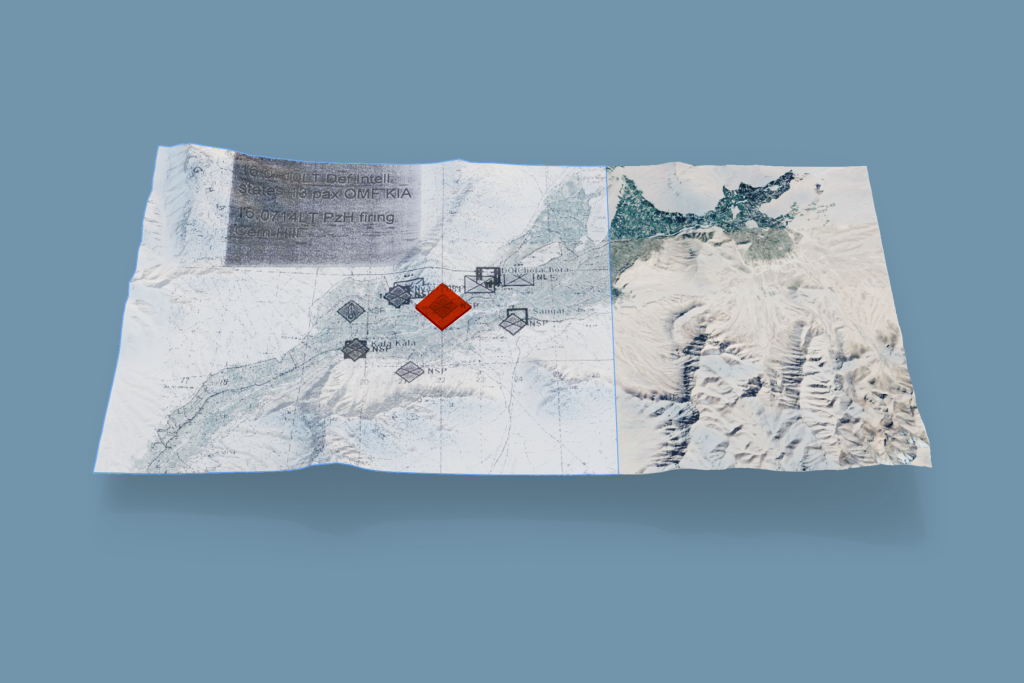

Channelling the power of open source techniques to document harm in conflict by listening to civilians' voices

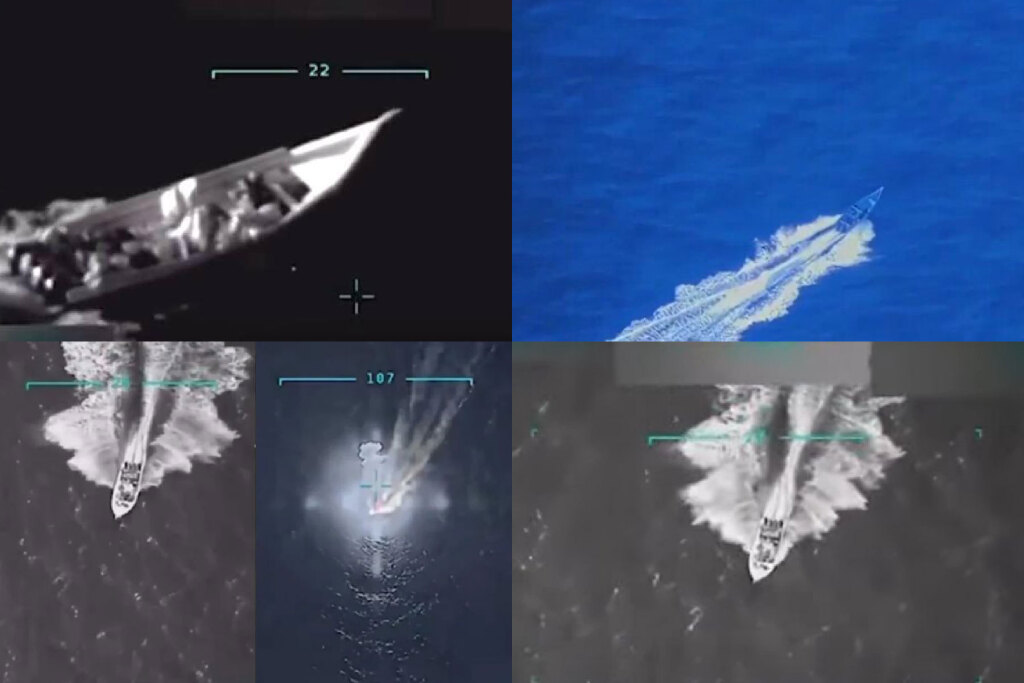

Ground-breaking investigations focusing global attention on civilian harm and identifying the perpetrators

Using the evidence base to push governments, militaries and others to better protect civilians in conflict